Key Takeaways

1. The Longitude Problem: A Centuries-Old Maritime Crisis

Here lies the real, hard-core difference between latitude and longitude — beyond the superficial difference in line direction that any child can see: The zero-degree parallel of latitude is fixed by the laws of nature, while the zero-degree meridian of longitude shifts like the sands of time.

Navigational dilemma. For centuries, sailors could determine their latitude with relative ease by observing the sun or stars, but finding longitude at sea remained an intractable problem. This fundamental difference stemmed from latitude's natural reference points (Equator, Tropics) versus longitude's arbitrary prime meridian, which could be placed anywhere. Without a fixed reference, a ship's east-west position was a constant mystery.

Dire consequences. The inability to accurately determine longitude led to catastrophic losses of life and treasure. Ships, forced to rely on "dead reckoning" (estimated position based on speed and direction), frequently missed their destinations, resulting in:

- Shipwrecks: The most infamous being the 1707 Scilly Isles disaster, where four British warships and nearly 2,000 men were lost.

- Scurvy: Prolonged voyages due to navigational errors meant sailors suffered from a lack of fresh food, leading to widespread disease.

- Economic havoc: Merchant and war ships clustered along known latitude routes, making them vulnerable to pirates and enemy attacks.

A national imperative. By the early 18th century, the longitude problem became a matter of national security and economic survival for maritime powers like Britain. The British Parliament, spurred by public outcry and the Whiston-Ditton proposal, passed the Longitude Act of 1714, offering a colossal prize of £20,000 (millions in today's currency) for a "Practicable and Useful" method of determining longitude at sea. This bounty ignited a fierce, four-century-long quest for a solution.

2. Astronomical Solutions: The Clockwork Universe's Promise

The rotating, revolving Earth is a cog in a clockwork universe, and people have told time by its motion since time began.

Celestial timekeeping. Many of the greatest scientific minds believed the solution to longitude lay in the heavens, using celestial bodies as a universal clock. The core idea was to compare local ship time (determined by the sun's highest point) with the time of a known astronomical event at a reference meridian. Early proposals included:

- Lunar eclipses: Too rare to be practical.

- Johannes Werner's lunar distance method (1514): Proposed mapping the moon's path against fixed stars, but lacked accurate star charts and instruments.

- Galileo's Jupiter moons (1610): Discovered Jupiter's satellites, whose frequent eclipses offered a celestial clock, but proved impossible to observe accurately from a rolling ship.

Observatories and data. The pursuit of astronomical solutions led to the establishment of major observatories in Paris (1666) and Greenwich (1675). Their primary mission was to map the heavens and refine lunar motion predictions. Key figures included:

- Giovanni Domenico Cassini: Published improved tables for Jupiter's moons, making Galileo's method viable on land for cartography.

- Ole Roemer: While observing Jupiter's moons, he made the groundbreaking discovery of the finite speed of light.

- John Flamsteed: The first Astronomer Royal, dedicated decades to compiling a precise star catalog at Greenwich.

Newton's influence. Sir Isaac Newton, though skeptical of mechanical clocks for sea use, believed the lunar distance method held the most promise. His Universal Law of Gravitation provided a theoretical framework for understanding the moon's complex motion, bolstering hopes that accurate lunar tables could eventually be created to guide ships across the oceans.

3. John Harrison: The Self-Taught Genius of Timekeeping

English clockmaker John Harrison, a mechanical genius who pioneered the science of portable precision timekeeping, devoted his life to this quest.

Humble beginnings. John Harrison, born in Yorkshire in 1693, was a carpenter's son with no formal education or apprenticeship in watchmaking. Despite this, his insatiable curiosity and mechanical aptitude led him to self-study, notably poring over Nicholas Saunderson's lectures on natural philosophy. This foundational knowledge, combined with his practical skills, set the stage for his revolutionary contributions.

Early triumphs. Harrison's early work demonstrated his extraordinary talent. His first pendulum clock, completed before he was twenty, was almost entirely made of wood, showcasing his innovative use of materials and design. He built two more identical wooden clocks, which, when tested against the stars, erred by no more than a single second a month—an unprecedented level of accuracy for the time.

A new direction. By 1727, the allure of the longitude prize turned Harrison's focus to marine timekeeping. He realized that his land-based innovations needed adaptation for the harsh conditions at sea. His journey to London in 1730, carrying plans for his first sea clock, marked the beginning of his direct engagement with the longitude challenge and the scientific establishment.

4. Harrison's Innovations: Overcoming Mechanical Obstacles

He invented a clock that would carry the true time from the home port, like an eternal flame, to any remote corner of the world.

Solving friction and lubrication. Harrison's genius lay in systematically addressing the fundamental problems that plagued earlier timekeepers at sea. His Brocklesby Park tower clock (c. 1722) pioneered oil-free operation by using lignum vitae, a naturally oily tropical hardwood, for bearings. This eliminated the issue of lubricants thickening or thinning with temperature changes, a critical step for marine accuracy.

Temperature compensation. Pendulums and balance springs were highly susceptible to temperature fluctuations, expanding or contracting and altering the clock's rate. Harrison's solutions included:

- Gridiron pendulum: Combining alternating strips of brass and steel, whose differential expansion canceled each other out, maintaining a constant length.

- Bi-metallic strip: A more streamlined version of the gridiron, used in later designs, which automatically adjusted the balance spring's effective length.

Maintaining precision at sea. The violent motion of a ship was another major hurdle. Harrison's "grasshopper escapement," used in his early clocks, was virtually friction-free and quiet, minimizing wear. For his marine timekeepers, he developed:

- Counterbalanced bar balances: In H-1 and H-2, these dumbbell-shaped balances were linked to oscillate in opposition, making them impervious to ship's motion.

- Caged roller bearings: An early form of anti-friction bearing, reducing wear in the gear train, a precursor to modern ball bearings.

These innovations, meticulously developed over decades, transformed the mechanical clock from a delicate instrument into a robust, precise timekeeper capable of withstanding the rigors of an ocean voyage.

5. The Chronometer's Triumph: H-4's Unprecedented Accuracy

I think I may make bold to say, that there is neither any other Mechanical or Mathematical thing in the World that is more beautiful or curious in texture than this my watch or Timekeeper for the Longitude . . . and I heartily thank Almighty God that I have lived so long, as in some measure to complete it.

From clock to watch. After nearly two decades developing his large sea clocks (H-1, H-2, H-3), Harrison made a surprising shift. Inspired by a precision pocket watch made for him by John Jefferys, Harrison conceived H-4, a five-inch diameter, three-pound timekeeper. This miniaturization was a monumental achievement, making the device truly portable and practical for a captain's cabin.

Exquisite engineering. H-4, completed in 1759, was a masterpiece of horological art and science. It incorporated Harrison's key innovations in a compact form:

- Bi-metallic temperature compensation: A refined strip to maintain accuracy despite temperature changes.

- Maintaining power: Kept the watch running during winding, preventing loss of time.

- Jeweled pallets: Diamonds and rubies were used in the escapement to drastically reduce friction and wear, a secret Harrison guarded closely.

- Detached escapement: A design that isolated the balance from the main power train, allowing it to oscillate more freely.

Proving its worth. H-4 underwent two rigorous sea trials to the West Indies. On its first voyage to Jamaica in 1761-62, it lost only five seconds on the outward journey, allowing William Harrison to correct the ship's estimated longitude by 60 miles. The second trial to Barbados in 1764 confirmed its extraordinary accuracy, determining longitude within ten nautical miles—three times better than the Longitude Act's requirement for the top prize. This performance unequivocally demonstrated the chronometer's superiority.

6. The Lunar Method: A Rivalry Fueled by Scientific Dogma

The clock of heaven formed John Harrison's chief competition for the longitude prize; the lunar distance method for finding longitude, based on measuring the motions of the moon, constituted the only reasonable alternative to Harrison's time-keepers.

A parallel path. While Harrison pursued his mechanical solution, astronomers continued to refine the lunar distance method, believing the heavens held the ultimate answer. This method involved measuring the angular distance between the moon and other celestial bodies (sun or stars) and comparing these observations to pre-calculated tables for a known meridian.

Key advancements: The lunar method became viable due to several critical developments:

- Hadley's Quadrant (1731): Independently invented by John Hadley and Thomas Godfrey, this reflecting instrument allowed accurate measurement of celestial angles from a moving ship, later evolving into the more precise sextant.

- Flamsteed's Star Catalog (posthumously 1725): Provided the necessary accurate positions of fixed stars.

- Halley's Lunar Observations: Decades of tracking the moon's complex, irregular orbit.

- Mayer's Lunar Tables (1750s): Tobias Mayer, with theoretical assistance from Leonhard Euler, created the first sufficiently accurate tables predicting the moon's position at twelve-hour intervals.

Complexity and limitations. Despite these advancements, the lunar method remained inherently complex and demanding. Navigators had to perform multiple observations, apply tedious calculations (correcting for refraction, parallax, and dip of the horizon), and rely on clear skies. The method was also unusable for several days around the new moon. This complexity, however, lent it an air of intellectual rigor and respectability among the scientific elite.

7. Nevil Maskelyne: The Antagonist and Advocate for Celestial Navigation

In all fairness, Maskelyne is more an antihero than a villain, probably more hardheaded than hard-hearted.

The "seaman's astronomer." Nevil Maskelyne, a Cambridge-educated astronomer, became the fifth Astronomer Royal in 1765 and a formidable opponent to Harrison. He was a staunch advocate for the lunar distance method, believing it to be the only truly scientific and universally accessible solution to the longitude problem. His methodical nature and unwavering belief in celestial navigation shaped his interactions with Harrison.

Institutionalizing the lunar method. Maskelyne dedicated his tenure to making the lunar method practical for all seamen. His major contributions included:

- The British Mariner's Guide (1763): An English translation of Mayer's tables with instructions for use.

- The Nautical Almanac (first published 1766): An annual publication providing pre-calculated lunar distances and other astronomical data, drastically reducing the computational burden for navigators.

- Tables Requisite: A companion volume to the Almanac, containing essential mathematical tables.

Biased opposition. Maskelyne's fervent belief in the lunar method led him to actively obstruct Harrison's claim to the prize. He conducted a highly controversial "trial" of H-4 at the Royal Observatory, where he claimed the watch's accuracy was erratic and unreliable, despite its proven performance at sea. Harrison accused Maskelyne of:

- Intentional distortion: Manipulating the testing conditions, such as placing H-4 in direct sunlight while measuring ambient temperature in the shade.

- Lack of oversight: Using infirm, elderly seamen from Greenwich Hospital as witnesses, who were unlikely to challenge his findings.

Maskelyne's actions, though perhaps driven by conviction rather than malice, created immense frustration for Harrison and prolonged his struggle for recognition.

8. The Battle for Recognition: Harrison vs. the Board of Longitude

The commissioners charged with awarding the longitude prize — Nevil Maskelyne among them — changed the contest rules whenever they saw fit, so as to favor the chances of astronomers over the likes of Harrison and his fellow "mechanics."

A rigged game. Despite H-4's undeniable success in two sea trials, the Board of Longitude, heavily weighted with astronomers and mathematicians, resisted awarding Harrison the full prize. They viewed his mechanical solution with suspicion, preferring the "scientific" elegance of the lunar method. Their tactics included:

- Demanding further trials: Despite H-4 exceeding the prize requirements, the Board insisted on more rigorous, often impractical, tests.

- Forcing disclosure: Harrison was compelled to dismantle H-4 and reveal its intricate secrets under oath to a committee of experts, including Maskelyne, before receiving half the prize money.

- Requiring replicas: To prove reproducibility, Harrison was ordered to build two exact copies of H-4, without access to his original watch or detailed plans, which Maskelyne had published.

Harrison's defiance. John Harrison, a man of simple birth but immense pride and conviction, found himself in a protracted battle against the scientific establishment. He viewed the Board's demands as unjust and an attempt to steal his invention. His frustration was palpable, leading to heated exchanges and his famous declaration that he would not comply "so long as he had a drop of English blood in his body."

The cost of genius. The struggle took a heavy toll on Harrison, both financially and emotionally. He spent decades of his life and personal fortune on the quest, only to face skepticism, delays, and what he perceived as deliberate sabotage. His large sea clocks (H-1, H-2, H-3) were even confiscated and left to deteriorate in storage at Greenwich, a symbol of the Board's disdain for his mechanical approach.

9. King George III's Intervention: Justice for the Inventor

By God, Harrison, I will see you righted!

A royal audience. Exhausted by the Board's intransigence and Maskelyne's relentless opposition, the elderly John Harrison, through his son William, appealed directly to King George III in 1772. The King, a keen amateur scientist with his own private observatory, had followed the longitude saga and was sympathetic to Harrison's plight.

A private trial. King George III personally intervened, taking H-5 (Harrison's fifth timekeeper, a replica of H-4) under his wing. He arranged for a six-week trial at his Richmond Observatory, overseen by his science tutor, S.C.T. Demainbray. The King himself held one of the three keys to the watch's box, ensuring fair oversight.

- Initial setback: H-5 initially performed erratically, causing Harrison embarrassment.

- Discovery of interference: The King realized that lodestones stored nearby were affecting the watch's delicate mechanism. Once removed, H-5 regained its composure.

- Proven accuracy: After ten weeks of daily observations, H-5 proved accurate to within one-third of a second per day, a resounding success.

Parliamentary resolution. Armed with this irrefutable evidence, King George III championed Harrison's cause, appealing directly to Prime Minister Lord North and Parliament for "bare justice." In June 1773, Parliament, bypassing the Board of Longitude, awarded Harrison £8,750, bringing his total reward to nearly the full £20,000 prize. This was a significant victory, not as the coveted prize itself, but as a bounty from Parliament, acknowledging his achievement despite the Board's resistance.

10. The Legacy of Longitude: From Unique Invention to Mass Production

Indeed, some modern horologists claim that Harrison's work facilitated England's mastery over the oceans, and thereby led to the creation of the British Empire — for it was by dint of the chronometer that Britannia ruled the waves.

A new industry. Harrison's success with H-4 sparked a boom in marine timekeeping. What was once a solitary quest became a burgeoning industry, with watchmakers across Europe striving to replicate and improve upon his designs. While early attempts by Pierre Le Roy and Ferdinand Berthoud were complex and expensive, English makers soon focused on mass production.

Pioneers of affordability. John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw emerged as the leading figures in making chronometers accessible. They simplified Harrison's intricate designs, developed new escapements (like the spring detent escapement), and refined manufacturing processes to reduce costs.

- John Arnold: A prolific maker, he produced hundreds of high-quality chronometers, often engraving "No. 1" on watches to market them. He focused on efficient production by outsourcing routine work.

- Thomas Earnshaw: Perfected the modern chronometer design, making it simpler and more robust. He was instrumental in transforming the chronometer from a bespoke curiosity into an assembly-line item, significantly lowering its price.

Widespread adoption. By the late 18th and early 19th centuries, chronometers became standard equipment for naval and merchant ships. Captain James Cook's voyages, particularly his second expedition, provided crucial validation, with Cook praising Kendall's copy of H-4 (K-1) as "our trusty friend the Watch" and "our never failing guide." The chronometer's superior accuracy and ease of use gradually eclipsed the lunar distance method.

11. Greenwich: The World's Meridian and Timekeeper

In 1884, at the International Meridian Conference held in Washington, D.C., representatives from twenty-six countries voted to make the common practice official. They declared the Greenwich meridian the prime meridian of the world.

A universal reference. Nevil Maskelyne, despite his opposition to Harrison, inadvertently cemented Greenwich's role as the world's prime meridian. By publishing the Nautical Almanac with all lunar distances calculated from Greenwich, he established it as the de facto reference point for navigators worldwide. Even French translations of the Almanac retained these Greenwich-based calculations.

Time and space unified. The triumph of the chronometer further solidified Greenwich's status. Sailors, using their chronometers to keep Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), naturally calculated their longitude relative to this meridian. This practical adoption eventually led to formal international recognition.

- Time Ball: In 1833, the Royal Observatory installed a time ball, dropped daily at 1 P.M., allowing ships in the Thames to precisely set their chronometers.

- International Meridian Conference (1884): Officially designated the Greenwich meridian as the prime meridian of the world, linking global time zones to GMT.

Enduring legacy. Today, the Old Royal Observatory at Greenwich remains the symbolic center of time and space. The Harrison timekeepers, meticulously restored by Lieutenant Commander Rupert T. Gould in the early 20th century, are preserved there, a testament to John Harrison's genius and perseverance. His invention, the marine chronometer, revolutionized navigation, enabled global exploration and trade, and fundamentally reshaped our understanding and measurement of the world.

Last updated:

Review Summary

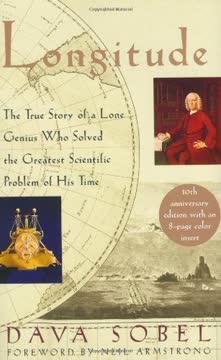

Longitude is praised as an engaging and accessible account of John Harrison's quest to solve the longitude problem in the 18th century. Readers appreciate Sobel's ability to make complex scientific concepts understandable, though some find the technical details lacking. The book is commended for its portrayal of Harrison's perseverance against political and scientific obstacles. While most reviewers find it captivating, a few criticize it for being dry or overly dramatized. Overall, it's considered a compelling blend of history, science, and human achievement.

Similar Books