Key Takeaways

1. The Oxford English Dictionary's Revolutionary Birth

A Dictionary," Trench said, "is an historical monument, the history of a nation contemplated from one point of view, and the wrong ways into which a language has wandered . . . may be nearly as instructive as the right ones."

A linguistic void. In Victorian England, despite a flourishing literary scene, no comprehensive English dictionary existed. Earlier attempts, like Samuel Johnson's monumental work, were either limited to "hard words" or reflected the editor's personal biases, failing to capture the full, evolving scope of the language. This absence was keenly felt by scholars and writers alike, who lacked a definitive guide to English usage, spelling, and etymology.

Trench's bold vision. In 1857, Dean Richard Chenevix Trench of Westminster delivered a pivotal lecture to the Philological Society, highlighting the "deficiencies in our English dictionaries." He proposed a radical new approach: a dictionary that would be an exhaustive "inventory of the language," not a prescriptive guide, documenting every word's history, nuances, and usage through illustrative quotations. This historical principle, tracing words from their first written appearance, was revolutionary.

The power of volunteers. Crucially, Trench recognized that such a colossal undertaking was beyond any single individual. He proposed recruiting a vast corps of unpaid amateur volunteers to read extensively and collect quotations. This democratic, collaborative model, though initially met with murmurs of surprise, was embraced by the Philological Society and ultimately made the seemingly impossible project of the "big dictionary" achievable, setting it apart from all predecessors.

2. James Murray: The Unconventional Scholar Behind the OED

"Nihil est melius quam vita diligentissima" (Nothing is better than a most diligent life).

A prodigious intellect. James Murray, born in 1837 to a tailor in the Scottish Borders, was a self-taught polymath with an insatiable thirst for knowledge. Despite leaving school at fourteen due to poverty, he mastered numerous languages, including French, Italian, German, Greek, Latin, Anglo-Saxon, and even Romany, and delved into geology, botany, and history. His early life was a testament to his "most diligent life," accumulating vast knowledge through eccentric and passionate self-study.

From bank clerk to lexicographer. After personal tragedy—the death of his first wife and infant daughter—forced him into a dreary bank clerk position in London, Murray's intellectual pursuits were temporarily sidelined. However, his passion for philology soon reignited, leading him to publish a respected work on Scottish dialect and join the prestigious Philological Society. His unique blend of rigorous scholarship and practical experience made him the ideal candidate to lead the ambitious dictionary project.

The OED's chosen editor. In 1878, after years of stalled progress and failed attempts by others, Murray was invited to Oxford to meet the Delegates of the Oxford University Press. His specimen pages and evident dedication impressed the formidable academics, leading to his appointment as editor of "A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles." This marked the true beginning of the OED's seventy-year journey, with Murray at its helm, ready to tackle the monumental task from his custom-built "Scriptorium."

3. Dr. William Minor: A Brilliant Mind Unhinged by War

The Civil War was well under way.

A privileged but troubled youth. William Chester Minor, born in Ceylon to American missionary parents in 1834, hailed from a distinguished New England family. His childhood was marked by early loss (his mother died when he was three) and exposure to the "lascivious thoughts" he harbored about young Ceylonese girls, which he later believed set him on a path to "insatiable lust" and "incurable madness." Despite these nascent struggles, he pursued an arduous medical education at Yale University.

The horrors of the Civil War. Graduating in 1863, Minor joined the Union Army as a surgeon during the American Civil War, a conflict characterized by new, devastating weaponry and primitive medicine. He was exposed to unimaginable carnage, gangrene, amputations, and the screams of dying men. This traumatic experience, particularly the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, is strongly suggested as the trigger for his latent madness.

A cruel act and its consequence. During the Battle of the Wilderness, Minor was allegedly forced to brand an Irish deserter with the letter "D" for cowardice. This act, which he believed would lead to the Irishman's eternal vengeance, became a central delusion in his developing paranoia. His mental state deteriorated rapidly, marked by promiscuity, severe headaches, and a growing conviction that he was being persecuted. By 1868, he was formally diagnosed with "monomania" and institutionalized.

4. Broadmoor Asylum: A Scholar's Unexpected Sanctuary

"A place out of which he that has fled to it, may not be taken."

Confinement in a "special hospital." After being found "Not Guilty on the Grounds of Insanity" for the murder of George Merrett in London in 1872, Dr. William Minor was committed to Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane. This forbidding red-brick institution, designed like a prison, was intended to securely house dangerous lunatics while offering "moral treatment." Minor, however, was deemed neither suicidal nor violent enough for the harsher "back blocks."

A life of privileged isolation. Instead, Minor was placed in Block 2, known as the "swell block," reserved for more genteel patients. Thanks to his considerable army pension and well-born status, he was granted two connecting rooms, kept unlocked by day, with an enchanting view. He furnished them comfortably, converting one into a library and the other into a painting studio. This unique environment, coupled with his intellectual capacity, allowed him to pursue his scholarly interests in relative peace.

Battling internal demons. Despite his comfortable surroundings, Minor's delusions persisted and worsened over the years. He believed small boys chloroformed him at night, intruders poured poison into his mouth, and electric currents were passed through his body. He barricaded his door, weighed himself daily, and was convinced of an "infernal criminal scheme" against him. Yet, amidst this torment, his scholarly side continued to develop, offering a crucial outlet for his tortured mind.

5. The Madman's Indispensable Contribution to the OED

"Dr. W. C. Minor of Crowthorne."

A call for volunteers. In 1879, James Murray issued a widespread appeal for volunteers to contribute quotations to the New English Dictionary. This pamphlet, explaining the meticulous process of collecting illustrative sentences for every word, eventually found its way to William Minor in Broadmoor. For Minor, languishing in intellectual isolation, this invitation offered a profound opportunity for "intellectual stimulus" and a "measure of personal redemption."

Minor's unique methodology. Minor responded with alacrity, volunteering his services. Unlike other readers who simply sent in slips as they encountered words, Minor devised a systematic approach. He created master word lists for hundreds of rare and obscure books in his extensive library, meticulously indexing each word's location. This allowed him to respond to specific word requests from the OED staff with astonishing speed and accuracy, providing precisely what was needed, when it was needed.

An invaluable asset. Minor's contributions quickly became indispensable. He sent hundreds of slips weekly, often providing the earliest known usage of words, reflecting his deep reading of seventeenth and eighteenth-century literature. The Oxford team, initially unaware of his circumstances, recognized him as a "meticulous man," "very prolific," and a "rare find." His name, "Dr. W. C. Minor of Crowthorne," was discreetly acknowledged in the preface to the first completed volume, a source of immense pride for the confined scholar.

6. An Unlikely Friendship Forged in Lexicography

"I sat with Dr. Minor in his room or cell many hours altogether before and after lunch, and found him, as far as I could see, as sane as myself, a much cultivated and scholarly man, with many artistic tastes, and of fine Christian character, quite resigned to his sad lot, and grieved only on account of the restriction it imposed on his usefulness."

The mystery unravels. For years, James Murray and his team were puzzled by their most prolific contributor, Dr. Minor, who lived so close yet never visited. The truth was revealed by chance in 1889 when a visiting Harvard librarian mentioned "poor Dr. Minor" and his "painful case." Murray was astonished to learn that his esteemed correspondent was a patient in a criminal lunatic asylum, a fact he had never suspected.

A bond of mutual respect. Deeply affected, Murray began to correspond with Minor more respectfully, careful not to betray his newfound knowledge. Eventually, urged by a mutual friend, Murray visited Broadmoor in January 1891. The meeting between the two men, uncannily similar in appearance with their long white beards, marked the beginning of a profound friendship. Murray found Minor to be "as sane as myself," a cultivated and scholarly man, resigned to his fate but eager for intellectual engagement.

Shared passions and solace. Their friendship, based on a shared love of words, endured for nearly two decades. They met dozens of times, discussing lexicographical problems, books, and even Minor's delusions, which Murray observed with sad affection. Minor's work for the OED, encouraged by Murray, became his primary solace and purpose, providing a vital link to the outside world and a measure of release from his paranoia.

7. Minor's Tragic Decline and Self-Inflicted Torment

He believed there had been a complete saturation of his entire being with the lasciviousness of over 20 years, during which time he had relations with thousands of nude women, night after night.

Worsening delusions. As the years passed, Minor's mental state deteriorated further. His paranoia intensified, with new obsessions about fiends in the floors, stolen flutes, and nightly abuses by attendants. The arrival of a stricter superintendent, Dr. Brayn, in 1895, further isolated Minor, who felt his privileges curtailed and his well-being disregarded.

A profound religious awakening. Around the turn of the century, Minor, raised a Congregationalist but long an atheist, experienced a religious reawakening, becoming a deist. This shift, however, brought with it a harsh self-judgment. He began to view his past sexual appetites as an intolerable sin, believing he was being punished by a vindictive deity for his "lascivious" life and "prodigious sexual appetites."

The ultimate self-mutilation. In December 1902, driven by his delusions and a desperate desire to purge his sin, Minor performed an "autopeotomy," amputating his own penis with a pen knife and throwing it into the fire. This horrific act, which he believed would sever him from his sexual desires and satisfy God, was a tragic culmination of his long-standing mental torment and guilt.

8. A Monumental Legacy and an Unsung Victim

George Merrett has become an absolutely unsung man.

Repatriation and final years. In 1910, after 38 years at Broadmoor, and with the intervention of Winston Churchill (then Home Secretary), the frail 76-year-old Minor was finally released and repatriated to the United States. He spent his last decade at St. Elizabeth's Federal Hospital in Washington, D.C., and later a hospital in Connecticut, where his delusions continued to worsen, compounded by senility and blindness. He died peacefully in 1920, largely forgotten.

The OED's completion. James Murray died in 1915, never seeing the OED's completion. The monumental dictionary, to which Minor had contributed scores of thousands of invaluable quotations, was finally finished in 1928, 70 years after its inception. It stood as a testament to the collaborative spirit of thousands of volunteers and the tireless dedication of its editors, becoming the definitive guide to the English language.

Remembering George Merrett. Amidst the grand narrative of the OED and the tragic life of Dr. Minor, the book poignantly reminds us of George Merrett, the innocent working-class man whose untimely murder set this extraordinary chain of events in motion. Merrett, a stoker and family man, died in poverty, leaving a pregnant wife and seven children. His grave remains unmarked, a stark contrast to the lasting literary monument his killer helped create, making him the "absolutely unsung man" of this remarkable story.

Last updated:

Review Summary

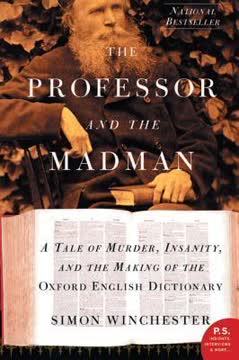

The Professor and the Madman tells the fascinating story of the Oxford English Dictionary's creation through the unlikely collaboration between editor James Murray and Dr. William Chester Minor, an American surgeon confined to Broadmoor asylum for murder. Reviews praise Winchester's engaging narrative style and the remarkable true story, though some criticize excessive speculation, repetitive writing, and disproportionate focus on biography over dictionary-making details. Most readers found the tale compelling despite its flaws, appreciating how Winchester made lexicography interesting. Common complaints include lack of citations, novelistic embellishments presented as fact, and sensationalized elements detracting from scholarly rigor.

Similar Books