Plot Summary

Waking in the Green Tent

An old man wakes in a hospital room, but in his mind, he's inside a green tent pitched in the middle of a strange square. His grandson, Noah, sits beside him, offering comfort. The tent is both a memory and a metaphor—a place of safety and adventure from their shared past. The old man is breathless and afraid, unsure of where he is, but Noah's presence is a gentle anchor. This surreal space is filled with echoes of their life together, blending reality and memory. The tent, a symbol of their bond, becomes the stage for a journey through the old man's fading mind, where love and fear intermingle, and the boundaries between past and present blur.

The Shrinking Square

The square in the old man's mind is shrinking, a metaphor for his deteriorating memory. He and Noah sit on a bench, surrounded by familiar yet misplaced objects—desks, calculators, and childhood toys. The square's boundaries contract as memories fade, and the old man laments the loss of coordinates and maps that once guided him. Noah, ever resourceful, tries to orient himself, but the rules of this place are different. The shrinking square is both a comfort and a prison, filled with the remnants of a life well-lived but now slipping away. The old man's faith in mathematics and his grandson remains, even as the world he knows diminishes.

Hyacinths and Forgotten Keys

Beneath the bench, hyacinths bloom, their scent evoking Christmas and the presence of Grandma. Among the flowers lie shards of glass and keys—symbols of memories as place and object and access to the past, now scattered and hard to grasp. Noah asks about the keys, but Grandpa's mind falters, unable to recall their purpose. The scene is rich with sensory detail, blending nostalgia with the pain of forgetting. The hyacinths, Grandma's favorite, anchor the old man to love and loss, while the keys represent the growing difficulty of unlocking his own memories. The boy's quiet observation and Grandpa's gentle touch reveal the tenderness and sorrow of their shared journey.

Blurry Faces, Fading Names

The blurry people move through the square, their faces blurred and identities slipping away. Grandpa waves to someone he cannot name, and Noah feels the weight of uncertainty. The absence of maps and compasses leaves them lost, and Grandpa's tears betray his fear and shame. The boy's longing for guidance is met with Grandpa's admission that some places cannot be navigated by logic or numbers. The emotional distance grows as the old man's mind fails him, and the once-reliable landmarks of memory dissolve. The chapter captures the ache of watching a loved one disappear before your eyes, even as they remain physically present.

The Girl with Hyacinths

The old man encounters the girl—his wife—her presence as vivid as the scent of hyacinths. Their conversation is a dance of longing and regret, recalling a lifetime together that now feels like the blink of an eye. She reassures him that their time was enough, even as he mourns its brevity. Their love is both a comfort and a source of pain, the last memory to abandon him. She urges him to explain his fading to Noah with the same respect and honesty he's always shown. Their exchange is tender, filled with the ache of impending loss and the enduring power of love.

Pi and the Power of Numbers

Grandpa and Noah play their favorite game, reciting the digits of pi. Numbers, once a source of certainty and guidance, now serve as a fragile bridge between them. The game is a ritual, a way to meet in the middle as Grandpa's mind contracts and Noah's expands. Mathematics, which once led men to the moon, now struggles to lead them home. The recitation is both playful and poignant, a testament to their bond and the inevitability of change. Grandpa's faith in numbers and in Noah is unwavering, even as the world becomes increasingly incomprehensible.

The Brain's Disappearing Roads

Grandpa tries to articulate the experience of losing his mind, likening it to searching for lost items in his pockets—first keys, then people. The roads in his mind are vanishing, shortcuts washed away by grief and time. He confesses to Noah that they are inside his brain, and it's getting smaller every night. The metaphor of the shrinking square and the closed roads captures the disorientation and helplessness of dementia. Noah's questions are met with honesty, and together they confront the fear and sadness of impending separation. The chapter is a meditation on the slow, painful process of letting go.

Ted's Unspoken Regrets

Ted, the old man's son and Noah's father, appears in the garden of memory, struggling with his own regrets. He and his father speak different languages—numbers and words—and their relationship is marked by misunderstanding and distance. Ted's childhood is filled with unmet expectations and a longing for connection. As an adult, he cares for his father, now diminished and confused, and tries to bridge the gap between them. The cycle of regret and apology repeats across generations, with Ted wishing he had been a better son and father. The chapter explores the complexities of familial love and the pain of things left unsaid.

The Archive of Memories

Grandpa describes the buildings on the horizon as archives, storing all the important moments, gifts, and memories of his life. Some buildings are crumbling, their contents lost to time, while others still shine with neon reminders: "Important!" "Remember!" The largest building holds "Pictures of Noah," a testament to the enduring love between grandfather and grandson. The archives are under siege, with memories blowing away like scraps of paper in the wind. The boy's presence is a lifeline, helping Grandpa hold onto what matters most, even as the rest slips away. The scene is both whimsical and heartbreaking.

Snowfall and the Art of Failing

As snow falls in the square, Grandpa teaches Noah about the nature of failure: the only true failure is not trying again. The snow, like the progression of dementia, covers Grandpa's ideas and memories, but the lessons he imparts remain. They discuss the fading of stars and brains, the slow realization of loss. The conversation is filled with warmth and wisdom, even as it acknowledges the inevitability of forgetting. Grandpa's belief in the boundless mystery of the human mind is a source of hope, and Noah's determination to remember for him is an act of love.

Practicing Goodbyes

Noah asks if they are here to learn how to say goodbye, and Grandpa admits that they are. Goodbyes are hard, inherited from Grandma, who refused to say them. They reminisce about her, her quirks, and the love she gave. Grandpa reassures Noah that they will have many chances to practice, and that their goodbye can be perfect—free of regret. The promise to remember and to let go is both a comfort and a challenge. The chapter is a gentle exploration of grief, memory, and the ways we prepare ourselves and our loved ones for loss.

The Shortcut Washed Away

Grandpa points out a road that has been washed away since Grandma died—a shortcut home that no longer exists. The loss of this path symbolizes the permanent changes wrought by grief and the impossibility of returning to the way things were. The conversation shifts to school, music, and the meaning of life, with Noah's simple answer—"Company. And ice cream."—offering a child's wisdom. The chapter underscores the importance of companionship and the small joys that persist even in the face of loss. The washed-out road is a poignant reminder that some things, once gone, cannot be reclaimed.

Company and Ice Cream

Noah shares his school assignment about the meaning of life, answering with "Company" and, when pressed, "Company. And ice cream." Grandpa delights in the answer, understanding its depth. Their exchange highlights the value of presence, laughter, and shared moments over grand achievements or philosophical answers. The simplicity of Noah's response cuts through the complexity of aging and loss, reminding both of them that love and togetherness are what truly matter. The chapter is a celebration of the ordinary, the everyday acts of kindness and connection that give life its meaning.

The First Dance

Grandpa recalls meeting his wife, their first dance, and the improbable odds of finding each other. Their love was fiery, argumentative, and extraordinary in its ordinariness. They built a life together, blending science and magic, logic and emotion. The memory of their first dance, their arguments, and their shared laughter sustains Grandpa even as his mind fades. The chapter is a tribute to the enduring power of love, the way it shapes and defines a life, and the comfort it provides in the face of mortality.

The Anchor and the Stones

The anchor by the boat is a symbol of childhood and the passage of time. Grandpa would place stones under it so that Noah could always be "short enough" to play in his office, preserving the magic of their relationship. The anchor represents stability, tradition, and the desire to hold onto moments as children grow. The ritual of adding stones is an act of love, a way to slow the inevitable march of time. The chapter explores the bittersweet nature of watching children grow and the creative ways we try to keep them close.

The Last Argument

Grandpa and Ted, his son, struggle with anger, regret, and the inability to communicate. Their arguments are fueled by guilt and the pain of watching a loved one decline. Ted wishes he had been a better son and father, while Grandpa mourns the time lost to work and misunderstanding. The arrival of Noah offers a chance for healing, as the love between grandfather and grandson bridges the gap between past and present. The chapter is a meditation on forgiveness, the limits of time, and the hope that comes with new generations.

The Balloon in Space

Noah promises to give Grandpa a balloon for his birthday, so he'll have something unnecessary and joyful when he goes into space—a metaphor for death and the unknown. The balloon is a symbol of love, memory, and the enduring connection between them. Noah's gesture is both playful and profound, offering comfort in the face of fear. The chapter captures the essence of their relationship: the ability to find laughter and meaning even as they prepare to say goodbye. The balloon becomes a tether, a promise that Noah will always be there to pull Grandpa back when he's scared.

The Road Home Together

In the end, the family gathers—Noah, Ted, and Grandpa—each holding the other through the journey of loss. They walk the road home together, offering company, comfort, and understanding. The green tent, the anchor, the archives, and the balloon all converge as symbols of love, memory, and the ways we care for one another. The story closes with the reassurance that, though the way home gets longer every morning, no one has to walk it alone. The legacy of love endures, carried forward by those who remain.

Characters

Grandpa

Grandpa is the central figure, a mathematician whose once-orderly mind is now succumbing to dementia. His love for numbers, logic, and his family defines him, but as his memory fades, he is forced to confront the limits of reason and the power of emotion. His relationship with Noah is tender and playful, filled with rituals and games that anchor him to the present. With his son Ted, the relationship is more fraught, marked by regret and unspoken longing. Grandpa's journey is one of letting go—of memories, of control, and ultimately of life itself—while striving to leave behind love and wisdom for those he cherishes.

Noah

Noah is Grandpa's grandson, a bright, compassionate boy who loves mathematics and adventure. He is both student and teacher, learning from Grandpa's stories and games while offering comfort and understanding as Grandpa's mind fades. Noah's innocence and resilience shine through as he navigates the complexities of loss, grief, and love. He becomes the keeper of family memories, promising to remember for Grandpa and to carry forward the lessons he's learned. Noah's presence is a source of hope and continuity, embodying the possibility of healing and connection across generations.

Ted

Ted is Grandpa's son and Noah's father, a man burdened by the weight of missed opportunities and unresolved conflict. His relationship with his father is complicated by differences in temperament and communication—Ted prefers words, Grandpa numbers. As an adult, Ted struggles to care for his ailing father while grappling with his own feelings of inadequacy and loss. The arrival of Noah offers a chance for reconciliation and redemption, as Ted witnesses the bond between his son and father. Ted's journey is one of acceptance, forgiveness, and the realization that love endures even when words fail.

Grandma

Though deceased, Grandma's presence permeates the story through scent, memory, and the enduring impact of her love. She is remembered for her hyacinths, her laughter, and her refusal to say goodbye. Her relationship with Grandpa was passionate and argumentative, filled with both conflict and deep affection. Grandma's wisdom and warmth continue to guide Noah and Grandpa, offering comfort and perspective as they navigate loss. She represents the enduring power of love and the ways in which those we've lost remain with us.

The Girl with Hyacinths

The girl, a younger version of Grandma, appears in Grandpa's mind as a symbol of first love and the enduring nature of their bond. She is both a memory and a guide, helping Grandpa come to terms with his fading mind and encouraging him to explain his condition to Noah with honesty and respect. Her presence is a source of comfort and a reminder that love transcends time and memory.

The Blurry People

The indistinct figures moving through the square represent the people and memories slipping away from Grandpa's mind. They are both familiar and unreachable, embodying the pain of forgetting and the isolation that comes with dementia. Their presence underscores the story's themes of loss, memory, and the struggle to hold onto what matters.

The Dragon, Penguin, and Owl

These stuffed animals, once gifts from Grandpa to Noah, populate the square as symbols of innocence, comfort, and the enduring bond between grandparent and grandchild. They serve as touchstones for shared memories and the magic of childhood, offering solace as the world becomes increasingly uncertain.

The Archive Buildings

The buildings on the horizon, filled with memories, gifts, and moments, symbolize the vastness and fragility of Grandpa's mind. As some buildings crumble and others shine, they reflect the selective nature of memory and the struggle to preserve what is most important. The archives are both a comfort and a source of anxiety, representing the ongoing battle against forgetting.

The Anchor

The anchor by the boat is a recurring symbol of stability, tradition, and the desire to hold onto childhood. Grandpa's ritual of adding stones to keep Noah "short enough" to play in his office is an act of love and resistance against the passage of time. The anchor embodies the bittersweet nature of watching children grow and the creative ways we try to keep them close.

The Balloon

The balloon, promised by Noah to Grandpa, is a symbol of love, memory, and the enduring connection between them. It represents the hope that, even as Grandpa "goes into space," he will carry with him a reminder of those who love him. The balloon is both playful and profound, a tether to the world and a promise that Noah will always be there to pull Grandpa back when he's scared.

Plot Devices

The Shrinking Square

The square in Grandpa's mind is the central metaphor for his experience with dementia. As the square shrinks, so too does his world, memories, and sense of self. This device allows the narrative to explore the internal experience of memory loss in a tangible, visual way, making the abstract process of cognitive decline accessible and emotionally resonant. The square's changing boundaries, the presence of familiar objects, and the appearance of loved ones all serve to illustrate the progression of the disease and the struggle to hold onto identity.

Memory as Place and Object

The story uses physical objects—keys, hyacinths, archives, anchors, and balloons—as symbols of memory, love, and loss. These items ground the narrative in sensory detail and provide touchstones for the characters as they navigate the shifting landscape of Grandpa's mind. The use of objects as repositories of meaning allows the story to explore the ways in which we hold onto the past and the pain of losing access to it.

Generational Echoes

The narrative structure weaves together the experiences of three generations—Grandpa, Ted, and Noah—highlighting the ways in which love, regret, and hope are passed down. The repetition of rituals, jokes, and arguments underscores the cyclical nature of family dynamics, while the possibility of healing and reconciliation offers hope for the future. The story's focus on generational relationships invites readers to reflect on their own family histories and the ways in which we learn to say goodbye.

Surrealism and Metaphor

The story's surreal elements—the tent in the hospital room, the shrinking square, the archive buildings—allow for a poetic exploration of dementia and loss. By blending reality and imagination, the narrative captures the disorienting, dreamlike quality of memory loss and the emotional truths that persist even as facts fade. The use of metaphor invites readers to engage with the story on both an intellectual and emotional level, deepening its impact.

Rituals and Repetition

The recurring games (reciting pi, telling jokes), rituals (adding stones to the anchor), and promises (to remember, to give a balloon) serve as anchors for the characters, providing stability and continuity in the face of change. These repeated actions reinforce the bonds between characters and offer comfort as they navigate the uncertainties of aging and loss.

Analysis

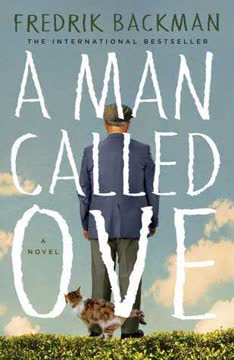

Fredrik Backman's "And Every Morning the Way Home Gets Longer and Longer" is a luminous meditation on memory, love, and the slow, painful process of letting go. Through the shrinking landscape of Grandpa's mind, Backman explores the devastation of dementia—not just for the one afflicted, but for the family who must learn to say goodbye long before death arrives. The novella's strength lies in its ability to render the abstract experience of cognitive decline into vivid, tangible metaphors: the shrinking square, the lost keys, the archives of memory. At its heart, the story is a love letter to intergenerational bonds, showing how rituals, jokes, and small acts of kindness become lifelines in the face of loss. Backman's message is clear: while we cannot halt the passage of time or the erosion of memory, we can offer each other company, understanding, and the promise to remember. In a world where goodbyes are inevitable, the story urges us to make them as perfect—and as loving—as possible.

Last updated:

Review Summary

And Every Morning the Way Home Gets Longer and Longer is a heartfelt novella about a grandfather with Alzheimer's and his relationship with his grandson. Readers praise Backman's poetic writing, emotional depth, and ability to capture complex family dynamics. Many found the story deeply moving, relatable, and a poignant exploration of love, memory, and loss. While some felt confused by the narrative structure, most were touched by the tender portrayal of the grandfather-grandson bond. The novella's brevity and impact left a lasting impression, with many readers experiencing strong emotional reactions.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.