Key Takeaways

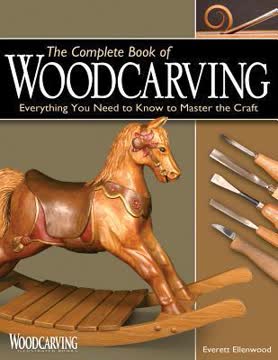

1. Woodcarving: A Timeless, Fulfilling Craft

Woodcarving is one of the oldest developed skills known.

An ancient art. Woodcarving has been a common thread through every nation and culture since mankind's beginning, with examples dating back to the New Stone Age (9000–7000 BCE) in China, Germany, and Africa. Ancient Egypt provides some of the best-preserved examples, showcasing figure, furniture, and relief carving, including the lifelike statue of Ka-Aper from 2500 BCE. This enduring presence highlights its fundamental role in human expression and utility.

Evolution through eras. From the functional items of the Bronze Age to the intricate religious carvings of the Gothic period (1200–1450 CE), woodcarving has adapted to societal needs and artistic movements. The Renaissance brought realistic foliage and symmetry, while masters like Grinling Gibbons (17th century England) elevated decorative carving to new heights with unparalleled delicacy and detail. In North America, early utilitarian carvings evolved into decorative and commercial pieces, experiencing revivals during the Depression era and post-WWII.

A lifelong passion. For the author, woodcarving is a stimulating yet relaxing hobby that offers endless creative possibilities, from simple patterns to intricate sculptures. It's a gratifying pursuit in an age of mass production, allowing one to transform a unique piece of wood into a personal work of art. The inherent beauty and character of wood make each carving a special and fulfilling part of life.

2. Understand Your Medium: Wood Anatomy, Selection, and Curing

The more you know about wood, the more effectively you can use it.

Tree's internal secrets. A tree's anatomy profoundly impacts its carving suitability. The trunk (bole) provides the most stable wood, while roots often have twisted grain and embedded dirt, making them challenging for beginners. Understanding internal characteristics like the pith (oldest, prone to cracking), annual rings (early/late wood, reaction wood), and cambium layer (bark adhesion) helps avoid costly carving errors.

Grain vs. figure. While often used interchangeably, grain refers to the arrangement of vessels in wood (e.g., straight, spiral), affecting how tools cut. Figure describes the patterns of grain or color (e.g., curly, fiddleback). Always cut across the vessels, not between them, to prevent splitting and maintain control.

Selecting and curing. Ideal carving woods weigh 25-50 pounds per cubic foot (10% moisture content) and include:

- Softwoods: Basswood (easy, subtle grain), Butternut (easy, beautiful grain), Catalpa (distinct grain).

- Hardwoods: Cherry (beautiful, prone to burn marks), Mahogany (straight grain, easy), Walnut (hard, beautiful), Birch (hard, uniform), Maple (dense, requires sharp tools).

- Found wood: Cottonwood bark, cypress knees, knots, driftwood offer unique challenges and inspiration.

Properly curing wood by air-drying, kiln-drying, or chemical-drying (e.g., Pentacryl) is crucial to remove internal water and prevent cracking.

3. Build Your Arsenal: Essential Carving Tools

Carving tools come in an almost infinite variety of shapes and sizes.

The foundational knife. A carving knife is often the first tool purchased. Beginners should opt for a straight blade no longer than 1½ inches for better control and safety. The handle should feel comfortable, as you'll spend many hours holding it. Detail knives, with sharper points, are for fine work, while chip carving knives are specifically designed for geometric chip removal.

Chisels, gouges, and veiners. These tools are categorized by their sweep (curvature) and width, following a universal numbering system.

- Chisels (#1-2): Flat or angled (skew/fishtail) for straight cuts and tight areas.

- Gouges (#3-9): Curved blades for concave, convex, and plunge cuts. Higher numbers indicate more pronounced curvature. Each gouge cuts a perfect circle of a specific radius.

- Veiners (#10-11): U-shaped tools for soft, deep cuts, often used for hair details.

Understanding these shapes helps select the right tool for specific tasks.

Specialty and quality. Beyond the basics, specialty tools like long-bent, short-bent, back-bent, dogleg, macaroni, fluteroni, and micro tools exist for specialized applications. When buying, prioritize high-quality carbon steel (Rockwell hardness R58c-R63c) for durability and edge retention. A good starter set includes a 1½" carving knife, ⅜" #9 gouge, ½" #5 gouge, and a ¼" 60-degree V-tool, with a 3/16" veiner and ⅜" or ½" #3 gouge as next additions. Avoid tool kits, as they often contain unused items.

4. The Golden Rule: Keep Your Tools Razor Sharp

I’m convinced more people stop carving because of dull tools than for any other reason.

The sharp advantage. A razor-sharp tool is not only more efficient but also safer, as it slices through wood with control, unlike a dull tool that requires excessive force. Achieving and maintaining this sharpness involves two key steps: shaping the tool to the proper cutting angle on sharpening stones and then polishing it to a keen edge on a strop.

Sharpening mediums. Various abrasive materials are available, each with unique characteristics:

- Oilstones: Traditional, efficient, but require honing oil and can cup over time.

- Diamond stones: Extremely efficient, fast-cutting, durable, and remain flat. Available in various grits from coarse to extrafine.

- Water stones: Create a slurry for fast sharpening and polishing, but wear quickly and require frequent flattening.

- Ceramic stones: Ideal for final sharpening and edge maintenance, very fine grit, and stay flat.

- Arkansas stones: Natural novaculite, excellent for putting a final, polished edge, but expensive and slow.

- Sandpaper: A cost-effective option for beginners, available in various grits, but wears out quickly.

The sharpening process. Regardless of the medium, the fundamentals remain:

- Evaluate: Visually check for straight sides, polish, microbevel, and absence of nicks. Physically test on soft wood for smooth, shiny cuts.

- Shape: Use coarse grits to remove major damage or reshape the blade, maintaining a consistent 23-degree cutting angle.

- Hone: Progress through finer grits, ensuring the burr (wire edge) rolls from one side to the other with minimal strokes.

- Strop: Use a strop loaded with honing compound to remove any remaining burr, polish the blade, and create a razor-sharp edge. Practice is key to mastering these repeatable steps.

5. Master the Cut: Techniques for Control and Precision

Every cut you make should have a specific purpose.

Knife fundamentals. The carving knife is central to hand carving, with two primary cuts:

- Pull cut (paring cut): Most common, pulling the knife towards you using hand muscles for control.

- Push cut: Pushing the knife away, often using the thumb as a fulcrum for high control.

Crucially, always cut across the grain (perpendicular to wood vessels) to ensure clean cuts and prevent splitting. Cutting into the grain (between vessels) causes tearing and loss of control.

Navigating wood grain. Wood has "negative and positive transition points" where the grain direction changes.

- Negative transition points: Cut towards these points from both directions for clean cuts.

- Positive transition points: Cut away from these points.

Understanding these points prevents the knife from following the path of least resistance and splitting the wood. A "controlled split" can be used strategically to remove large amounts of wood quickly or to achieve maximum strength in thin pieces by aligning vessels.

Stop cuts and gouge work. A "stop cut" severs wood fibers up to a certain point, controlling the depth of material removal. Never pry out waste wood, as this dulls and damages tools; instead, make light cuts to sever all fibers. Gouges and V-tools offer versatility:

- Gouges: Used for concave, convex, and plunge cuts. When carving, ensure both wings of the gouge are visible to prevent tearing.

- V-tools: Act as two flat chisels and a small gouge, ideal for outlining and defining details.

Practice with these tools, including exercises like carving circles or V-tool flowers, builds proficiency and confidence.

6. Blueprint to Block: Developing and Transferring Your Design

The most important step is to take time to develop a clear mental image of what you want before you start to actually carve.

Solidifying the vision. Before touching wood, invest time in developing a clear mental image of your desired carving. This preparation saves time and significantly improves the outcome. Resources for idea development are diverse:

- Clay models: Excellent for full-size or scaled models, allowing easy addition, subtraction, and modification of design elements. Oil-based clay on an armature is recommended.

- Visual aids: Plastic or composition objects, sketches, photos (taken from various angles at consistent distances), and the internet provide invaluable reference.

- Personal library: Create a subject library of images and references, masking out irrelevant parts to focus on specific details like an eye or nose. A mirror can also serve as a personal model.

Pattern creation and transfer. Patterns are essential for laying out a carving.

- Materials: Regular paper for tracing, cardboard/cardstock for reusable templates, and tracing/carbon/graphite paper for complex designs.

- Methods: Patterns can be glued to wood for band saw cutting, drawn freehand (often with rulers and compasses), or traced using carbon paper for intricate details.

- Blanks and roughouts: Pre-cut blanks (major waste removed) or roughouts (more detailed pre-carving) can save significant time, especially for complex shapes.

Wood preparation and mounting. Select wood based on grain, deformities, and curing status. For strength and aesthetics, lay out patterns so the grain enhances the carving and runs through fragile areas. When ready to carve, always mount the wood in a vise whenever possible. This frees both hands for tool control, enhancing safety and precision.

7. Explore the Spectrum: Diverse Carving Styles and Forms

Once you begin carving, only your imagination will limit what you can create.

Two-dimensional artistry. Carving isn't just about depth; two-dimensional styles focus on surface work:

- Incised carving: Only the outline is carved, often for furniture or lettering.

- Chip carving: Removing geometric or free-form chips, a decorative and ancient art.

- Intaglio: Negative relief, where the subject is carved into a recess, common for molds.

- Relief carving: Wood is removed around an object to make it appear raised. This includes low relief (minimal projection), high relief (at least half the object projects), and pierced relief (areas completely removed).

Architectural and natural forms. Specialized styles cater to specific aesthetics and materials:

- Architectural carving: Designs carved into or attached to furniture and architectural elements, with acanthus carving being a popular, flowing, stylized form.

- Bark carving: Utilizing thick, dense bark (like cottonwood) for unique fantasy buildings or wood spirits, adapting to each piece's natural shape.

Carving in the round (three-dimensional). This category encompasses subjects visible from all angles:

- Realistic carving: Aims for true-to-life detail in birds, animals, fish, or human figures, often requiring extensive reference.

- Stylized carving: Emphasizes form and smooth lines over intricate detail, often left unpainted to showcase wood grain.

- Caricature carving: Exaggerates distinctive features for humorous or expressive effect, often in basswood.

- Flat-plane carving: A Scandinavian style characterized by simple, controlled knife cuts leaving flat surfaces.

- Utilitarian carving: Functional items like spoons or bowls, which can incorporate other styles.

- Whimsies: Nonfunctional, entertaining carvings, often featuring interlocking parts from a single piece of wood.

8. The Final Flourish: Painting and Finishing Your Masterpiece

If you ask one hundred carvers how they finish a carving, you’ll get about one hundred different answers.

Three finishing paths. The choice of finish depends on the desired aesthetic:

- No finish: Leaves the wood bare, but offers no protection from oils, grime, or dust.

- Enhance wood grain: Uses clear coatings to protect and highlight the natural beauty of the wood.

- Paint: Applies color, obscuring some or all of the wood grain.

Always ensure the carving is clean, free of "fuzzies," and pencil lines before applying any finish.

Enhancing natural beauty. Clear finishes fall into two categories:

- Surface finishes: Form a protective layer on the wood.

- Varnish: Durable, heat/water/chemical resistant, adds a golden tint (except water-based), available in gloss/satin/flat.

- Shellac: Natural resin, fast-drying, good sealer, but weak resistance to heat/water.

- Lacquer: Fast-drying, durable, usually sprayed, but highly flammable and toxic fumes.

- Paste wax: Inexpensive, easy, but soft and least durable.

- Penetrating finishes: Absorb into the wood, hardening it while allowing grain and texture to show.

- Linseed oil: Derived from flaxseed, golden tint, slow-drying, not very durable.

- Tung oil: Most durable natural oil, water-resistant, cures to a matte finish, will not darken.

- Danish oil: Blend of varnish and oil, easy to apply, durable, inexpensive.

Proper disposal of oil-soaked rags is crucial to prevent spontaneous combustion.

Adding color. Stains and paints offer various ways to color wood:

- Stains: Color the wood without protecting it.

- Prestain wood conditioner: Prevents blotchiness on end grain.

- Pigment stain: Finely ground pigments, highlights grain, can be mottled.

- Dye stain: Penetrates deeply, colors all wood, may mask grain, water-based can raise grain.

- Gel stain: Thick consistency, less blotchy, won't run.

- Shoe polish: Stain in wax binder, tints surface fibers, limited colors.

- Paints:

- Acrylic paint: Water-based, opaque, fast-drying, good for washes and layering.

- Artist oil paint: Pigment with oil binders, more transparent, slow-drying (good for blending), can bleed if wood isn't sealed.

- Oil pencils: Quick, clean, semi-opaque, blendable, good for detail.

Always test paint and finish compatibility on scrap wood before applying to your carving.

9. Safety First: Ergonomics and Workshop Essentials

Most of all, use common sense. If you ever get the feeling that what you’re planning to do may not be safe, don’t do it.

Ergonomic workspace. Your carving area should be set up for comfort and efficiency. Whether sitting or standing, ensure your work surface is at an ergonomic height (about one hand's width below your elbow) to minimize strain. A simple carving table with stops can provide a portable, chip-collecting surface.

Protecting yourself. Safety is paramount in woodcarving:

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE):

- Dust mask (NIOSH N95): Essential for any dust-producing activity.

- Goggles: Protect eyes from flying debris.

- Earmuffs: For noisy power tools.

- Carving glove & thumb guard: Protect hands when holding the carving.

- Tool handling: Always keep tools razor sharp for control. Never put body parts in the blade's path. Use proper grips for hand and power tools, ensuring the power tool bit spins so wood is removed towards you.

- Workshop safety: Maintain a clean work area, take breaks, never try to catch falling tools, have a first-aid kit, and properly dispose of rags soaked in flammable liquids to prevent spontaneous combustion. Install smoke alarms and fire extinguishers.

Essential accessories. Beyond tools, several accessories enhance the carving experience:

- Lighting: Incandescent for shadows, full-spectrum for true colors, magnifiers for detail.

- Dust collection: Central vacuums, shop vacuums, or air filtration systems are crucial for managing fine dust.

- Clamping devices: Vises, C-clamps, dogs, or grip sticks immobilize the carving, allowing both hands to control the tool and improving safety. Always use wood buffers with metal clamps.

- Measuring devices: Dividers, compasses, and calipers ensure accuracy and proportion.

- Hand tools: Mallets, handsaws, rifflers, rasps, stamps, and even dental tools for intricate cleaning.

Power tools like band saws, scroll saws, drills, and routers can save time but require careful use and adherence to safety protocols.

Last updated: