Key Takeaways

1. Gaiman's Worlds: A Tapestry of Philosophy and Myth

In Gaiman’s re-creation of reality, characters like Richard, Coraline, and Shadow, the ex-con protagonist of American Gods, often discover enchanted alternate worlds that bump up against the margins of the mundane, the reasonable, and the rational.

Fictive travel literature. Neil Gaiman's stories invite readers on philosophical journeys through imaginary topographies, where characters like Richard Mayhew (Neverwhere), Coraline, and Shadow (American Gods) encounter fantastic alternate realities. These narratives serve as "fictive travel literature," offering richly described encounters with unfamiliar places that challenge mundane perceptions. The pleasure lies in exploration, mapping philosophical rather than geographic territories.

Transformation through encounter. Gaiman's protagonists are often forced or tricked into these unfamiliar landscapes, where their identity and lives are threatened. To survive, they must map and decode these fantastical worlds, which in turn compels them to re-evaluate their understanding of themselves and their "real" world. This transformative effect extends to the reader, who, like the characters, embarks on a lifelong journey of self-discovery and a new perception of the ordinary.

Beyond tourism. Unlike tourists who remain detached, Gaiman's characters and readers become travelers, engaging with and being transformed by their experiences. Gaiman believes stories are "good lies that say true things," building worlds that offer hope, wisdom, kindness, or comfort to those who need them. His narratives immerse readers, leaving them changed forever, transforming them from mere tourists into genuine travelers of the imagination.

2. Causality and Chance: The Art of Divine Misdirection

“It was crooked,” said Shadow. “All of it. None of it was for real. It was just a setup for a massacre.”

Orchestrated coincidences. In American Gods, Mr. Wednesday (Odin) masterfully orchestrates a series of seemingly random events—Laura's death, Shadow's prison release, flight cancellations—to manipulate Shadow into becoming his pawn. This elaborate "set-up" exploits our tendency to perceive causality in "constant conjunctions" (Hume's idea that repeated co-occurrence leads us to infer cause and effect), even when a deeper, hidden cause is at play.

The two-man con. Wednesday and Loki execute a sophisticated confidence scheme, using misdirection to conceal their true intentions. Loki, disguised as Low Key Lyesmith, identifies Shadow's weak spot (his love for Laura), which Wednesday then exploits. By admitting to general dishonesty, Wednesday distracts Shadow from the specific, immediate deception, making Shadow believe he's making free choices when he's actually being subtly guided.

Shadow's awakening. Shadow, initially a "student of chance" perfecting coin tricks, eventually realizes he's been the "sucker" in Wednesday's epic scam. This epiphany, occurring as he hangs from the mythical Yggdrasil, allows him to actively participate in the game he didn't know he was playing. A golden coin, given by Mad Sweeney and dropped into Laura's grave, introduces a true element of chance, resurrecting Laura and setting off an unforeseen causal chain that ultimately thwarts Odin's plan.

3. Fiction's Truth: Beyond Plato's Lies, Aristotle's Insight

“Any impossibilities there are in his descriptions of things are faults. But from another point of view they are justifiable, if they serve the end of poetry—if . . . they make the effect of . . . the work . . . more astounding.”

Plato's critique. Plato famously criticized poets like Homer for spreading "falsehoods" about the gods, depicting them as contemptible, deceitful, and emotionally volatile. He believed such fantastic literature was dangerous, corrupting public morality by presenting unworthy role models and distracting from the pursuit of truth and rational order. From Plato's perspective, American Gods, with its conniving, flawed deities, would be an appalling work of art.

Aristotle's defense. In contrast, Aristotle defended fiction, recognizing its value beyond literal truth. He argued that stories, even impossible ones, can be worthwhile if they are:

- Intellectually stimulating: Offering "leisure spent in intellectual activity."

- Exploratory: Revealing "what could happen" rather than just "what has happened," making poetry "more philosophic and of graver import than history."

- Aesthetically pleasing: Making the work "more astounding" through fantastic elements.

Catharsis and internal logic. Aristotle also believed that experiencing extreme emotions through fictional characters could lead to "catharsis," purging negative feelings in the audience. He emphasized that a good story must make internal sense, with events and character development unfolding logically from its established premises, even if those premises are improbable. American Gods, despite its absurd premise, adheres to this internal logic, making it a significant work of literature by Aristotelian standards.

4. Belief as Survival: Gods, Tools, and American Pragmatism

“Believe,” said the rumbling voice. “If you are to survive, you must believe.”

Instrumentalism in belief. American Gods portrays deities as manifestations of human belief, serving as "tools" for survival and social order. This aligns with American pragmatism, which values usefulness over absolute truth. As societies evolve, old gods (like Czernobog's hammer) become obsolete, replaced by new gods (like Media's television set) that better serve contemporary needs.

Gods as survival tools. The novel's central conflict is the gods' struggle for survival, driven by the need for human belief. The buffalo man's advice to Shadow, "If you are to survive, you must believe," underscores this instrumentalist view. Gods are crafted by human needs, and their existence depends on their continued utility.

- Old gods: Jupiter, Czernobog, Anansi

- New gods: Media, Technology, Broadcast

- Obsolescence: Gods are "as quickly taken up as they are abandoned."

Liberty and individualism. American philosophy, rooted in European ancestry but adapted to new conditions, emphasizes usefulness and survival. Gaiman's American gods, like American philosophers, often operate in isolation, pursuing individual spheres of influence. Shadow's desire for independence—"I think I would rather be a man than a god. We don’t need anyone to believe in us. We just keep going anyhow"—reflects the American ideal of liberty and self-determination, even if it leads to a "shadow world of mental constructs."

5. The Nature of Reality: Dreams, Monads, and Conscious Information

“The DREAMWORLD, the DREAMTIME, . . . call it what you WILL—is as much part of ME as I am part of IT.”

Dreams as objective travel. The Sandman posits a Dreamworld that exists independently of individual minds, suggesting our dreams are actual travels to this realm. This challenges the common view of dreams as subjective, random neural firings. While Descartes questioned if waking life was a dream, Gaiman's narrative implies dreams could be experiences of an objectively real, mind-independent place, albeit one with different natural laws.

Monads and archetypes. Leibniz's monadology, a form of idealism, suggests that reality is composed of simple, indivisible, non-physical entities (monads) with inherent mental properties (perception and appetition). These monads can combine to form physical objects, minds, and Platonic Forms. This framework helps explain how Gaiman's gods, as archetypes or concepts, can become physically embodied through human belief, which itself is a cluster of monads.

Information and consciousness. David Chalmers' panprotopsychism, combined with Information Theory, offers a mechanism: if information is fundamental, and has both physical and phenomenal (mental) aspects, then a shared belief (information/monad) across many minds could "level up" to become a conscious, physical entity. Gaiman's universe, where thoughts and beliefs give birth to gods, aligns with this idea, suggesting that the universe itself is made from information, and that mental events can affect physical ones because they are all fundamentally monads.

6. Moral Visibility: Confronting Invisibility and Indifference

“He could not believe” that Jessica was “simply ignoring the figure at their feet.”

The curse of invisibility. Neverwhere explores social invisibility, where characters like Richard Mayhew become literally unnoticeable after helping Door from London Below. This magical invisibility serves as a metaphor for real-life dehumanization and indifference, where individuals or groups are excluded from moral consideration. Richard's plight—losing his job, fiancée, and the ability to be perceived—mirrors the social ostracism faced by the poor and homeless.

Degrees of exclusion. Invisibility can be partial, where certain needs or roles are ignored (e.g., asking "how are you?" without caring), or radical, where a being is completely excluded from the moral community. Richard's joy when a taxi stops for him signifies regaining his "visibility" and status as a person worthy of moral consideration. This exclusion is often based on arbitrary criteria like social class, race, or belonging to "London above."

The loving gaze. Richard's compassionate response to Door's suffering, in contrast to Jessica's indifference, highlights the importance of a "loving gaze"—an "intuitive openness" that prioritizes empathy over self-interest or rationalization. This attentive, concerned way of seeing allows one to overcome ignorance of others' particularities and challenge social misconstructions of marginalized groups. Richard's decision to help Door, despite personal cost, transforms him into a "fuller, happier person," suggesting that combating invisibility makes us better.

7. The Value of Experience: Death's Mortal Lessons

“One day a small girl looked at me when I took her, all icy and distant and vain, and she said, ‘How would you like it?’ That was all she said, but it hurt me and it made me think.”

Empathy through mortality. Gaiman's Death, initially cold and distant, chooses to become mortal for one day every century to understand the lives she takes. This practice, inspired by a dying girl's challenge, aims to cultivate compassion. It raises the philosophical question of whether certain truths—like the feeling of being alive or the fear of death—can only be learned through first-person experience, rather than abstract knowledge or third-person descriptions.

The limits of knowledge. Frank Jackson's "Mary the color scientist" thought experiment explores whether knowing all physical facts about color vision is equivalent to experiencing color. Similarly, Death's mortal sojourn suggests that while one might intellectually grasp the concept of mortality, the subjective "what it's like" to taste an apple or feel fear requires direct experience.

- Mary's Room: Can a scientist who knows everything about color learn something new by seeing red?

- Death's experience: Can an immortal truly understand mortality without living it?

The "Soul Man" effect. Death's awareness that her mortality is temporary (the "Soul Man" effect) complicates her learning, as she knows she will return to her immortal state. However, her experiences teach her the "meaning of life"—to appreciate the "little moments" that make life matter, a lesson easily forgotten amidst life's distractions. This continuous cycle of mortal experience reinforces her understanding, enabling her to offer genuine comfort to the dying.

8. Growth Through Ghosts: Crafting Self in the Graveyard

“I know my name,” he said. “I’m Nobody Owens. That’s who I am.”

Self-creation in the uncanny. The Graveyard Book blends coming-of-age and Gothic ghost story elements to explore self-making. Bod, raised by ghosts, learns about identity and societal rules from both the living and the dead. His unique upbringing in a cemetery—a "heterotopia" that is both real and otherworldly—forces him to confront the uncanny and define himself in a world where death is a constant presence.

Postmodern identity. Bod's journey challenges traditional notions of a fixed "self" and rigid social norms. Living among diverse ghosts (Roman, witch, poet), he navigates a "complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing," rather than a singular cultural truth. This aligns with Lyotard's postmodern idea that individuals create their own identities from fragments, seeing themselves as less dependent on "big picture" narratives and more responsible for self-creation.

Transcending boundaries. Bod's strength lies in his ability to violate and transcend boundaries, rather than merely conforming to them. His name, "Nobody Owens," signifies an autonomous and universal identity—he is "nobody but himself," owning his existence. His actions, like befriending an outcast witch or using ghostly powers against bullies, go against conventional expectations, demonstrating a moral growth that embraces contradictions and ultimately allows him to leave the entire system behind, ready to face "actual Life."

9. Redemption's Paradox: Forgiving the Unforgivable in Hell

“forgiveness forgives only the unforgivable. One cannot or should not forgive; there is only forgiveness, if there is any, where there is the unforgivable.”

Lucifer's abandonment. In The Sandman: Season of Mists, Lucifer closes Hell, leaving its governance to the Angels Duma and Remiel. They aim to transform Hell from a place of eternal punishment into one of redemption, mirroring Heaven. This shift is spurred by Morpheus's guilt over condemning Nada, highlighting the idea that true forgiveness, as Derrida argues, applies only to the "unforgivable."

The paradox of forgiveness. Derrida's paradox states that only truly atrocious, unimaginable acts can be genuinely forgiven, as trivial wrongs merely require overlooking. This preserves the value of forgiveness, making it dependent on the profound nature of the wrong and the willingness of the wronged party to forgive. In Hell, the damned, having committed unforgivable sins, desire punishment, not the Angels' imposed redemption, which they perceive as a deeper torment.

Redemption vs. punishment. The Angels' new Hell, focused on "refining" flames and "purity," aims for rehabilitation, akin to Foucault's reformatory prison system. However, this altruistic goal is imposed without the prisoners' consent or understanding, creating a "sugarcoated despair." The lack of communication and respect for the prisoners' desire for punishment devalues their humanity, ironically limiting the possibility of true redemption, which requires a collaborative effort and genuine compassion.

10. The Good Life: Character, Authenticity, and Living with the Dead

“You’re always you, and that don’t change, and you’re always changing, and there’s nothing you can do about it.”

Judging life's events. Bod's tragic beginning—his family's murder—paradoxically leads to an extraordinary life in the graveyard. This illustrates the distinction between being "sorry for" an event (recognizing its moral tragedy) and being "sorry that" it happened (wishing it never occurred, even if it led to personal benefit). Bod's ability to overcome tragedy and live a good life stems from his character and how he responds to adversity.

Virtues and friendship. Aristotle's concept of virtues (excellences of character) is central to living a good life. Bod acquires virtues like righteous indignation, wisdom (from Silas), and friendliness through his interactions with the graveyard's inhabitants. These virtues not only enable moral actions but also enrich life through meaningful friendships, which Aristotle considered intrinsically valuable.

- Moral virtues: Bravery, temperance, charity, truthfulness, friendliness, wittiness, modesty, patience.

- Wisdom: Silas's "cool, sensible, and unfailingly correct" advice.

- Friendship: "Without friends no one would choose to live."

Authenticity and self-possession. Existentialist authenticity—being true to oneself rather than conforming—is a core virtue for Bod. His name, "Nobody Owens," signifies his unique, self-made identity, distinguishing him from the inauthentic "ghouls" who leech identities from others. Bod's journey is one of self-fashioning, embracing his freedom to be himself. Ultimately, his self-possession, owning his own being, is the hallmark of his fully realized self, a "wonderful gift of mortality."

11. Eternal Recurrence: Batman's Infinite Affirmation

“Do you know the only reward you get for being Batman? You get to be Batman.”

Nietzsche's cyclical existence. Neil Gaiman's Batman: Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader? explores Nietzsche's concept of eternal recurrence: the idea that life's events repeat endlessly. This concept, initially appalling, becomes a profound affirmation of life, shifting focus from a teleological (destination-driven) purpose to the inherent meaning of living itself. For Nietzsche, embracing eternal recurrence signifies a deep satisfaction with one's life.

Batman's ultimate fate. Gaiman applies eternal recurrence to Batman, offering a philosophically meaningful conclusion to a myth without a conventional end. The narrative presents contradictory accounts of Batman's death, undermining any singular "truth" or teleological reward. Instead, Batman's ultimate fate is to be reborn as infant Bruce Wayne, reliving his life—his trauma, his crime-fighting, his triumphs, and defeats—infinitely.

Affirming the journey. This cyclical ending transforms Batman into a Nietzschean Overman, one who finds meaning not in a final victory or external justification, but in the act of being Batman. The reward is the repetition itself, forcing readers to value the mythos for its inherent journey. Gaiman's use of eternal recurrence crystallizes a fundamental truth about Batman: we want him to be Batman forever, endlessly fighting, finding meaning in the very act of his existence.

12. Fictional Beings: The Metaphysics of Created Characters

What makes the claims about Aziraphale true, if Aziraphale does not exist?

The problem of non-existent entities. Philosophers grapple with how we can make true claims about fictional characters like Aziraphale (Good Omens) if they don't exist in the real world. The correspondence theory of truth, which requires claims to represent facts about the world, seems to break down when applied to fiction. This problem is compounded when authors like Gaiman revise mythological figures, seemingly altering their established properties.

Abstract artifacts. Amie Thomasson's theory proposes that fictional characters are "abstract artifacts" created by their authors. Like concrete artifacts (e.g., a book), abstract artifacts (e.g., Aziraphale) are intentionally created and depend on their creators, but lack physical location. This allows for different authors to create distinct "tokens" (e.g., Gaiman's Death vs. Pratchett's Death) of the same "type" (the concept of Death).

Family resemblances and linguistic acts. The challenge then becomes defining what features unite different tokens of a fictional type. Wittgenstein's concept of "family resemblances" suggests that not all instances of a type share one common characteristic, but rather a network of overlapping similarities. Furthermore, authors "create" these abstract entities through linguistic acts, similar to how a minister's words can change reality ("I now pronounce you husband and wife"). Gaiman's creative license, while seemingly violating historical constraints, instead brings new abstract entities into existence, enriching our understanding of "what they may be."

Last updated:

Review Summary

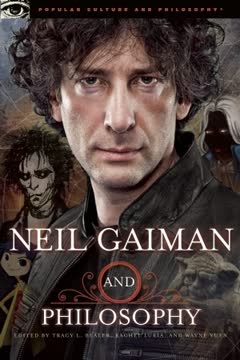

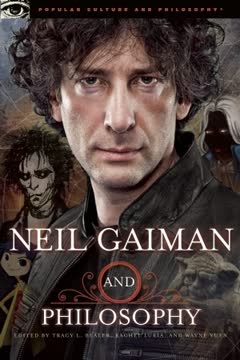

Neil Gaiman and Philosophy receives mixed reviews, with an average rating of 3.55/5. Some readers find it insightful, praising its accessibility and range of perspectives on Gaiman's work. Others criticize it for being uneven, tedious, or overly esoteric. Positive reviews highlight the book's exploration of philosophical themes in Gaiman's stories, while negative reviews mention disappointment with the focus on others' interpretations rather than Gaiman's own philosophies. Several readers note that the quality of essays varies, with some being more engaging and relevant than others.

Popular Culture and Philosophy Series Series