Key Takeaways

1. Slavery's Legacy: A New Form of Bondage

The convict’s condition [following the Civil War] was much worse than slavery. The life of the slave was valuable to his master, but there was no financial loss … if a convict died.

Post-Civil War reality. Following the Civil War, Mississippi, like much of the South, faced economic devastation and a profound shift in its labor system with the emancipation of slaves. This tumultuous period saw a desperate need for cheap labor to rebuild the agricultural economy, particularly in the fertile Yazoo Delta. The state's existing penal system was in ruins, creating a vacuum that would be filled by a new, exploitative system.

Black Codes' purpose. In 1865, Mississippi enacted the first "Black Codes," a series of laws designed to control the newly freed black population and force them back into agricultural labor. These codes criminalized "vagrancy," "mischief," and "insulting gestures" specifically for black individuals, leading to mass arrests and convictions for minor offenses. The intent was clear: to maintain a racial caste system and ensure a steady supply of black labor.

Economic shift. The convict lease system emerged as a "solution" to the state's labor shortage and overflowing jails. Unlike slaves, whose value represented a capital investment, convicts had no such protection. Their lives were expendable, and their deaths incurred no financial loss, making them a brutally efficient labor source for plantations, railroads, and mines. This system effectively created a "second slavery" where black bodies were exploited for profit.

2. The Profit Motive: Convict Leasing as Economic Engine

The most profitable prison farming on record thus far is in the State of Mississippi … which received in 1918 a net revenue of $825,000…. Given its total of 1,200 prisoners—and subtracting invalids, cripples, or incompetents—it made a profit over $800 for each working prisoner.

Economic solution. Convict leasing was initially conceived as a temporary measure to address the post-Civil War crisis of overcrowded jails and destroyed infrastructure. However, it quickly transformed into a highly profitable enterprise, generating millions in revenue for state and local governments, and even more for private contractors. This system turned the "problem" of black criminality into a remarkable economic gain.

Revenue generation. States like Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia leased out their entire prison populations to private companies, often for meager fees, while the lessees reaped enormous profits from the forced labor. This revenue helped lower taxes for white citizens and funded public projects, making the system politically popular despite its inherent brutality. The real beneficiaries were powerful businessmen and planters who gained access to an inexhaustible supply of cheap, pliable labor.

Industrial development. Convict labor played a crucial role in the South's industrialization, particularly in:

- Railroad construction: Convicts laid thousands of miles of track across the region.

- Coal mining: They comprised a significant portion of the mining workforce in Alabama and Tennessee.

- Turpentine industry: In Florida, convicts performed the dangerous and exhausting work of extracting resin.

This reliance on convict labor also served to intimidate free workers, suppressing wages and undermining unionization efforts.

3. Racialized Justice: Black Codes and Unequal Punishment

“You can’t believe a thing a negro says,” one judge remarked. “They will tell you just what they think you want to hear.”

Discriminatory laws. The Black Codes, passed immediately after the Civil War, were explicitly designed to control black labor and social behavior. These laws created specific offenses for "free negroes," such as "vagrancy" and "insulting gestures," ensuring a constant flow of black individuals into the penal system. This legal framework laid the groundwork for systemic racial discrimination in justice.

"Pig Law" impact. In 1876, Mississippi's "Pig Law" redefined "grand larceny" to include the theft of farm animals or property valued at ten dollars or more, punishable by up to five years in state prison. This law disproportionately affected impoverished black individuals, leading to a dramatic increase in black convictions and quadrupling the state's convict population. It was a direct pipeline to the convict lease system.

Judicial bias. The criminal justice system was deeply biased against black defendants. Juries were overwhelmingly white, black testimony was often discounted, and legal representation was rare. This meant that black individuals faced harsher sentences for minor offenses, while white offenders often received leniency or avoided conviction entirely. The concept of "Negro law" emerged, where justice was applied based on race, not universal standards.

4. Brutality and Dehumanization: The Convict's Ordeal

“As a rule,” another legislative committee noted, “the life of a [Texas] convict is not as valuable in the eyes of the sergeants and guards and contractors as that of a dog.”

Subhuman conditions. Convicts in the lease system endured appalling conditions, often worse than those of slavery. They were housed in "rolling iron cages" or primitive log stockades, sleeping shackled on bare boards amidst filth and vermin. Food was often spoiled, and medical care was minimal, leading to widespread disease and suffering.

Systematic torture. Physical punishment was rampant and brutal, with guards and overseers employing various methods to maintain discipline and maximize labor:

- Whipping: The "bull whip" or "Black Annie" was a common tool, often used until the victim's flesh was "puffed and curled like a bacon rind."

- Chains and irons: Convicts were shackled, sometimes for days, and forced to work in leg irons.

- Mutilation: Prisoners were known to chop off fingers or toes, or inflict other self-injuries, in desperate attempts to escape labor or gain a pardon.

- Sweatboxes: Coffin-sized boxes used for isolation, where temperatures became unbearable.

Expendable lives. The high mortality rates in convict camps were staggering, often reaching 9-16% annually in Mississippi and up to 45% in some railroad camps. Convicts were literally worked to death, with little to no accountability for their employers. This expendability reinforced the dehumanization of black prisoners, whose lives held no value beyond their labor.

5. Parchman Farm: The Quintessential Penal Plantation

On the whole, the conditions under which prisoners live in [Parchman], their occupation and routine of living, are closer by far to the methods of the large antebellum plantation worked by numbers of slaves than to those of the typical prison.

Vardaman's vision. Established in 1904 under Governor James K. Vardaman, Parchman Farm was designed as a self-sufficient penal plantation, a monument to his vision of "socializing" black convicts within the limits of their "God-given abilities." Spanning 20,000 acres in the Yazoo Delta, it lacked traditional prison walls or cells, instead resembling a vast cotton plantation. Its primary goal was profit, not rehabilitation.

The "trusty system." Parchman's unique structure relied heavily on the "trusty system," where selected inmates, often serving long sentences for murder, guarded other convicts ("gunmen"). These "trusty-shooters" were armed with rifles and shotguns, given privileges, and incentivized with pardons for shooting escapees. This system created a brutal hierarchy, isolating trusties from other inmates and making them fiercely loyal to white sergeants.

Daily life and "Black Annie." The daily routine for gunmen involved dawn-to-dusk labor in the cotton fields, often under extreme heat, with strict quotas enforced by mounted drivers. Work chants, a legacy of slavery, set the pace. Discipline was maintained through "Black Annie," a thick leather strap used for public whippings. This system, while profitable, reduced inmates to a state of "abject slavery," with their lives dictated by the whims of sergeants and trusties.

6. The White Chief's Vision: Vardaman and White Supremacy

A VOTE FOR VARDAMAN IS A VOTE FOR WHITE SUPREMACY, THE SAFETY OF THE HOME, AND THE PROTECTION OF OUR WOMEN AND CHILDREN.

Populist demagogue. James K. Vardaman, known as the "White Chief," rose to power in Mississippi by skillfully channeling the anxieties of poor white farmers. He blamed wealthy Delta planters and black laborers for economic woes, using inflammatory rhetoric to unite whites across class lines. His political campaigns were characterized by mass rallies and appeals to racial fear.

Racist ideology. Vardaman's platform was explicitly built on white supremacy. He asserted that black people were "lazy, lying, lustful animals" and advocated for the abolition of black education, believing it "spoiled a good field hand and made an insolent cook." He also called for the repeal of the Fifteenth Amendment and the Declaration of Independence, arguing they did not apply to "wild animals and niggers."

Inciting violence. Vardaman frequently invoked the specter of "black fiends" preying on white women, using the false narrative of black rape to justify extreme violence. He openly defended lynching, stating that white men would be "justified in slaughtering every Ethiop on the earth to preserve the honor of one Caucasian home." His rhetoric fueled a climate of racial terror, leading to Mississippi becoming a leader in lynchings during his era.

7. Lynching and Legal Executions: Tools of Social Control

If they happened to lynch the wrong person—well, that too served a purpose by reminding other 'niggers' of their place.

Prevalence of lynching. Mississippi earned the grim distinction of being the "lynching state," a title it held for a century. Post-Reconstruction, lynching evolved into the region's most popular form of vigilante justice, primarily targeting young black men perceived as challenging racial boundaries. These acts were not just about punishment but about reinforcing the racial hierarchy through terror.

Public spectacle. Lynchings often became public spectacles, drawing large crowds, including women and children, in a carnival-like atmosphere. Victims were subjected to horrific torture, such as burning alive, dismemberment, and mutilation, with body parts sometimes distributed as "souvenirs." These events served as brutal public warnings, demonstrating the consequences of perceived transgressions against white supremacy.

Blurred lines. The distinction between lynching and legal execution was often blurred. Public executions, especially before state control, frequently resembled mob actions, with predetermined verdicts and gruesome displays of death. The legal system, influenced by racial bias, often expedited trials and sentences for black defendants accused of crimes against whites, ensuring that "the negro rapist must die," whether by mob or by law.

8. The "Other" Convicts: White Men and Black Women at Parchman

“One white convict gives me more trouble than three Negroes,” Superintendent Oliver Tann remarked in the 1930s. His belief was widely shared.

White male defiance. While Parchman was predominantly black, white male convicts, comprising about 10-30% of the population, were perceived differently. They were seen as more defiant and less amenable to the "nigger work" of field labor, often resisting orders and engaging in "strikes" or self-mutilations. Their presence challenged the racialized nature of the prison's discipline, as white opinion viewed white criminals as bolder but less threatening to the social order than black ones.

Black female vulnerability. Black women, though a small percentage of the state prison population, faced unique challenges. They were typically young, poor, and convicted of violent offenses, often domestic disputes. Their camp was segregated from men, but sexual exploitation and rape were common, often at the hands of male sergeants and trusties. Authorities largely ignored violence against black women, reflecting the broader societal indifference to their plight.

Unequal justice for women. White women were rarely sent to Parchman, and when they were, their numbers were minuscule. Their crimes were often treated with leniency, with judges reluctant to subject them to "nigger work" or the harsh conditions of the penal farm. This stark contrast highlighted the racial and gender biases embedded in Mississippi's criminal justice system, where chivalry was reserved for white women, regardless of their crimes.

9. The Illusion of Freedom: Pardons and the System's Caprice

“Wouldn’t it be the wisest course to grant Berry’s pardon, turn him out, and take chances on his killing another negro?”

Capricious clemency. Mississippi's lack of parole laws until 1944 meant that pardons were the primary path to early release, making the system highly arbitrary and susceptible to corruption. Inmates needed the backing of white patrons, sergeants, and superintendents, whose recommendations were crucial. The process was deeply paternalistic, with white "friends" vouching for a convict's "good character" or "humble" demeanor.

Racial bias in pardons. Pardons were often granted based on racial considerations, particularly for black-on-black crime. Murders committed "at a negro frolic" or where "one nigger killed another" were frequently dismissed as ordinary events among a "savage, impulsive race," leading to lenient treatment or early release. This indifference to black victims fueled high levels of violence within the black community and fostered a cynical disregard for the law.

Extreme examples. The Goldberger pellagra experiment exemplified the system's moral bankruptcy, where white convicts were promised pardons for risking their lives in a nutritional study. Similarly, the case of John Randolph, a black man framed for rape, revealed how innocent black individuals could languish for years due to judicial indifference and the absence of white advocates. These cases underscored the system's caprice and its profound racial inequities.

10. Civil Rights Confronts Parchman: Federal Intervention and Reform

While confinement, even at hard labor and without compensation, is not necessarily cruel and unusual punishment, it may be so when conditions and practices become so bad as to be shocking to conscience of reasonably civilized people.

Parchman as a weapon. In the 1960s, as the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum, Mississippi officials weaponized Parchman Farm, using it to house and "break down" activists challenging segregation. Freedom Riders, arrested for "breach of the peace," were subjected to harsh conditions in the Maximum Security Unit, including overcrowding, lack of basic amenities, and psychological torment, though physical violence was often restrained due to national scrutiny.

Legal challenges. The brutal treatment of civil rights activists, particularly the Natchez demonstrators, drew the attention of federal courts and civil rights lawyers. Organizations like the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under the Law filed landmark lawsuits, bypassing the biased state courts. These legal battles exposed the systemic abuses at Parchman and laid the groundwork for federal intervention.

Landmark ruling. In 1972, Federal District Judge William C. Keady's ruling in Gates v. Collier declared Parchman's conditions unconstitutional, citing violations of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. Keady condemned the prison's racial segregation, inadequate housing, medical care, and the brutal trusty system. His sweeping order mandated immediate desegregation, the abolition of trusties, the hiring of professional guards, and comprehensive plans for modernizing the prison.

11. Enduring Challenges: Parchman's Legacy and Modern Prisons

“I look around today and see a place that makes me sad.”

Slow reform, new problems. Despite Judge Keady's landmark ruling, reform at Parchman was slow and met with resistance, leading to endless compliance orders. While racial segregation ended and professional guards replaced trusties, new challenges emerged. The end of forced labor, coupled with inadequate vocational programs, led to widespread inmate idleness, contributing to a surge in gang activity and inmate-on-inmate violence.

Shifting landscape. Parchman transformed from a self-sufficient penal plantation into a modern correctional facility, albeit with lingering issues. The convict population tripled, and its budget soared, making it one of the largest prisons in the U.S. The staff diversified, with a majority of black guards and administrators, but the fundamental power dynamics and the challenges of managing a large, often violent, inmate population remained.

Modern Parchman's struggles. Today, Parchman is a mix of old and new, with modern facilities alongside remnants of its past. While lethal injection has replaced the gas chamber, and new programs like Regimented Inmate Discipline (boot camps) are in place, the core issues of inmate violence, idleness, and the struggle for meaningful rehabilitation persist. The sentiment of an old inmate, "I look around today and see a place that makes me sad," encapsulates the complex and often disheartening legacy of a prison deeply intertwined with Mississippi's racial history.

Last updated:

Review Summary

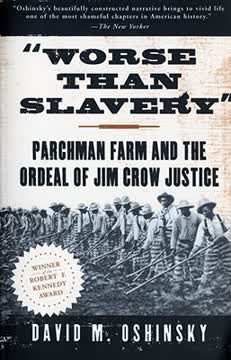

Worse Than Slavery examines Parchman Farm prison and Mississippi's convict leasing system following the Civil War. Reviews consistently describe the book as well-researched, devastating, and essential reading for understanding systemic racism and mass incarceration's origins. Readers emphasize how freed Black Americans were arrested for minor or fabricated offenses and worked to death under conditions reviewers compared to slavery and concentration camps. Many found the content horrifying yet necessary, noting the book contextualizes modern criminal justice issues within Jim Crow era brutality and racial violence that persisted through the twentieth century.

Similar Books