Key Takeaways

1. Science's Dual Legacy: Creation and Catastrophe

The Reich leadership, however, tasted something very different when the lightning war was extinguished by the firestorms of the Allied bombers, when the Russian winter froze the caterpillar tracks of their tanks and the Führer ordered everything of value within the Reich destroyed to leave nothing but scorched earth for the invading troops.

Dual-use discoveries. Scientific breakthroughs, while often intended for progress, frequently possess a terrifying duality, capable of both immense benefit and unimaginable destruction. This is starkly illustrated by the origins of Prussian Blue, a pigment that became the precursor to cyanide, a poison used in Nazi gas chambers. The same chemical structure that yielded a beautiful color for art also became the agent of mass extermination.

Haber's paradox. Fritz Haber, the Nobel laureate who developed the Haber-Bosch process to synthesize nitrogen from the air, simultaneously created chlorine gas, the first weapon of mass destruction used in World War I. His nitrogen fertilizers saved hundreds of millions from famine, fueling a demographic explosion, yet his gas caused unspeakable agony, leading his wife to commit suicide in protest of his perversion of science.

- Haber-Bosch process: Enabled artificial nitrogen fertilizer, feeding billions.

- Chlorine gas: Caused soldiers to drown in their own phlegm, leading to Clara Immerwahr's suicide.

Scheele's accidental poisons. Carl Wilhelm Scheele, a genius chemist, discovered cyanide by accident while working with Prussian Blue. Unaware of its toxicity, he also manufactured an arsenic-based pigment, Scheele's green, which adorned Napoleon's wallpaper and slowly poisoned him. Scheele himself died young from his habit of tasting new substances, a testament to the dangerous, often unforeseen, consequences of chemical exploration.

2. The Singularity: Where Reality Breaks Down

The problem arose when too much mass was concentrated in a very small area, as occurs when a giant star exhausts its fuel and begins to collapse.

Schwarzschild's impossible solution. Karl Schwarzschild, a physicist serving in the trenches of World War I, miraculously derived the first exact solution to Einstein's equations of general relativity. His calculations, however, revealed a deeply unsettling anomaly: if enough mass were concentrated in a small enough space, space-time would not merely bend but tear apart, creating an inescapable abyss of infinite density—the Schwarzschild singularity.

A monster of mathematics. Initially, Schwarzschild dismissed this singularity as a mathematical error, an "imaginary monster" that could not exist in the real world. Yet, the concept haunted him, spreading across his mind "like a stain," superimposed over the horrors of the trenches. He realized that if such a thing existed, it would be eternal and inescapable, located at both ends of time, defying common sense and the very foundations of physics.

The point of no return. Schwarzschild's final, agonizing calculations, made while his body was consumed by a rare disease, predicted that any object compressed beyond a certain limit (the Schwarzschild radius) would be trapped forever, disappearing from the universe. He feared that a similar "singularity" could arise from a sufficient concentration of human will, a "black sun dawning over the horizon," with a point of no return that would be crossed unknowingly.

3. The Inaccessible Universe of Pure Abstraction

If researchers want to apprehend my work, they must first deactivate the thought patterns that they have installed in their brains and taken for granted for so many years.

Mochizuki's incomprehensible proof. Shinichi Mochizuki, a Japanese mathematician, published a 600-page proof for the a+b=c conjecture, one of number theory's most important problems. However, his work was so bizarre, abstract, and unlike any known mathematics that, years later, no one has managed to fully comprehend it, leading to accusations of hoax or psychological imbalance.

A universe of his own. Mochizuki developed an entirely new branch of mathematics, Inter-Universal Teichmüller Theory, which he described as requiring mathematicians to "deactivate" their ingrained thought patterns. He created a complete mathematical universe, of which he remains the sole inhabitant, refusing to explain his work or engage with critics, eventually withdrawing his proof and stating that "certain things should remain hidden."

Grothendieck's curse. Mochizuki's master, Alexander Grothendieck, was a towering figure in 20th-century mathematics who revolutionized the understanding of space and time. He sought an "absolute understanding" of mathematics, creating intricate theoretical architectures and concepts like "schemes" and "topoi." His ultimate quest for the "motive," the "heart of the heart" of mathematics, led him to an abyss of abstraction, eventually causing him to abandon mathematics, burn his writings, and live as a hermit, fearing the "shadow of a new horror" his discoveries might unleash.

4. Quantum Reality: Beyond Human Intuition

What Schrödinger writes makes scarcely any sense. In other words, I think it’s bullshit.

The clash of titans. The early 20th century saw a fundamental schism in physics regarding the nature of the atom. Erwin Schrödinger, with his elegant wave equation, offered a visualizable model where electrons behaved like waves, seemingly reining in the chaos of the quantum world. Werner Heisenberg, however, vehemently rejected this, arguing that the subatomic realm was "far stranger than you can imagine," defying all classical intuition and visualization.

Heisenberg's abstract truth. Tormented by pollen allergies, Heisenberg retreated to Heligoland, where he developed "matrix mechanics," an exceptionally abstract theory based solely on measurable data. He replaced visual models with complex tables of numbers, discovering that electrons were neither waves nor particles but existed in a realm of pure mathematical possibility. His method, though repulsive in its complexity, accurately described atomic phenomena without recourse to imagery.

Schrödinger's beautiful illusion. Schrödinger's equation, while mathematically equivalent to Heisenberg's, offered a comforting, intuitive picture of the atom. Yet, even Schrödinger himself struggled with the meaning of his "wave function" (ψ), which required imaginary numbers and moved in multidimensional space, making his waves "not a part of this world." He had hoped to simplify the atomic world but instead gave birth to a greater mystery, a "mathematical chimera" that was unsettlingly precise yet physically indecipherable.

5. The Uncertainty Principle: The End of Objective Reality

God does not play dice with the universe!

A fundamental limit. Heisenberg's profound insight, born from a hallucinatory night in Copenhagen, revealed an absolute limit to what can be known about the world. He discovered that certain complementary properties of quantum objects, such as position and momentum, cannot be simultaneously known with perfect precision. The more accurately one is measured, the more uncertain the other becomes, a principle that applies to all matter, though imperceptibly at macroscopic scales.

The Copenhagen Interpretation. This discovery, championed by Niels Bohr, formed the core of the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics. It posited that reality does not exist independently of observation; a quantum object has no intrinsic properties until it is measured. Between measurements, it exists in a "space of possibilities," a "spectrum of probabilities," challenging the very notion of an objective, independently existing physical world.

Einstein's defiance. Albert Einstein, a master of visualization and a staunch believer in a deterministic universe governed by rational laws, vehemently rejected this probabilistic view. His famous retort, "God does not play dice with the universe!", encapsulated his refusal to accept that chance could be enthroned at the heart of matter. Despite his efforts to find a "hidden variable" or a grand unified theory, he died alienated from a generation that had embraced the inherent uncertainty of the quantum realm.

6. The Psychological Toll of Radical Discovery

Often I have been unfaithful to the heavens. My interest has never been limited to things situated in space, beyond the moon, but has rather followed those threads woven between them and the darkest zones of the human soul, as it is there that the new light of science must be shone.

Schwarzschild's torment. Karl Schwarzschild, a brilliant astronomer, was consumed by his discovery of the singularity, which spread across his mind "like a stain" amidst the horrors of war. His physical illness, pemphigus, mirrored his internal struggle, as he cataloged his wounds while his mind raced to understand the void his equations had opened. He feared a correlation between extreme mass concentration and human will, leading to a "creeping madness."

Heisenberg's delirium. Werner Heisenberg's quest to understand the quantum world pushed him to the brink of a nervous breakdown. His allergic reaction, isolation, and feverish work in Heligoland led to vivid hallucinations and nightmares, blurring the lines between reality and delirium. He experienced a split personality, arguing with himself, and was drugged by a stranger in Copenhagen, leading to a profound, yet terrifying, epiphany about the nature of uncertainty.

Grothendieck's withdrawal. Alexander Grothendieck, after revolutionizing mathematics, underwent a radical metamorphosis, abandoning his career, family, and friends. He became obsessed with ecology and pacifism, founded a commune, and engaged in extreme self-mortification, convinced that scientists were "marching like sleepwalkers towards the apocalypse." His final years were spent in total isolation, burning his life's work, driven by a fear that his profound understanding of mathematics could unleash a "shadow of a new horror" upon mankind.

7. The Interwoven Fabric of Existence

In every creature sleeps an infinite intelligence, hidden and unknown, but destined to awaken, to tear the volatile web of the sensory mind, break the chrysalis of flesh, and conquer time and space.

Vedanta's influence. Erwin Schrödinger, during a period of personal and professional despair in post-WWI Vienna, found solace and profound insight in the philosophy of Vedanta. He embraced the idea that all individual manifestations are reflections of Brahman, the absolute reality underlying the world's phenomena. This philosophical lens allowed him to see the interconnectedness of all beings, from a dismembered horse to the women tearing its flesh, recognizing a shared essence.

Grothendieck's schemes. Alexander Grothendieck's mathematical genius lay in his ability to perceive underlying relationships and unify disparate branches of mathematics. He expanded the notion of a "point" into a complex inner structure and created "schemes" that revealed a grander reality behind every algebraic equation. He believed that true vision involved combining complementary views to understand that "all are, in actuality, part of the same thing," aspiring to illuminate the "motive" at the crux of the mathematical universe.

The cosmic uterus. Miss Herwig, a young tuberculosis patient who deeply influenced Schrödinger, shared his fascination with Eastern philosophy. She interpreted his Kali nightmare not as a horror but as a blessing, a symbolic castration necessary for the birth of a new consciousness. She described Kali's black skin as the "cosmic uterus in which all phenomena gestated," echoing the Vedantic idea of an underlying unity from which all forms emerge and to which they return.

8. The Unforeseen Consequences of Knowledge

What new horrors would spring forth from the total comprehension that he sought? What would mankind do if it could reach the heart of the heart?

Haber's ecological guilt. Fritz Haber, the "man who pulled bread from air," confessed in a letter to his wife an "unbearable guilt" not for the human lives his gas had taken, but because his nitrogen extraction method had so altered the planet's natural equilibrium that he feared the future belonged not to mankind but to plants. He envisioned a world suffocated by "terrible verdure," a chilling prophecy of unintended ecological consequences.

Grothendieck's fear of total comprehension. Alexander Grothendieck, at the peak of his mathematical powers, became consumed by the destructive potential of science. He warned his students that they were "marching like sleepwalkers towards the apocalypse," fearing what mankind would do if it could reach the "heart of the heart" of mathematics. His subsequent withdrawal from society was an act of "protection of mankind," driven by a refusal to contribute to a "shadow of a new horror."

Heisenberg's suppressed vision. During his hallucinatory night in Copenhagen, Heisenberg glimpsed not only the fireflies of quantum leaps but also "thousands of figures who had surrounded him in the forest, as if wishing to warn him of something, before they were carbonized in an instant by that flash of blind light." This terrifying vision of mass destruction, which he could not bring himself to confess, foreshadowed the atomic bomb, a weapon whose feasibility he would later investigate for the Nazis, unaware of its true destructive power until Hiroshima.

9. The Human Element in Scientific Progress

The physicist—like the poet—should not describe the facts of the world, but rather generate metaphors and mental connections.

Bohr's poetic approach. Niels Bohr, Heisenberg's mentor, believed that when discussing atoms, language could serve as nothing more than a kind of poetry, generating metaphors and mental connections rather than literal descriptions. This philosophical stance influenced Heisenberg to abandon classical concepts and embrace the "radical otherness" of the subatomic world, highlighting how personal perspectives and mentorship shape scientific paradigms.

Schrödinger's personal catalysts. Schrödinger's groundbreaking wave equation was born from a confluence of personal struggles and unexpected encounters. His professional humiliation by Peter Debye, a violent attack of tuberculosis, and his intense infatuation with Miss Herwig, a young patient in a sanatorium, all fueled his manic creative outburst. His dreams, his guilt, and his philosophical discussions with the girl profoundly shaped his intuitive leap into wave mechanics.

Eccentricity and genius. The lives of these scientists were marked by profound eccentricities that often intertwined with their genius. Alan Turing, the father of computing, chained his mug to a radiator and wore a gas mask for allergies. Grothendieck slept on a door and spread his own excrement as fertilizer. Heisenberg, in his delirium, saw yellow spots on dervishes' tunics as the secret to his matrices. These personal quirks underscore that scientific progress is not a sterile, objective process, but a deeply human endeavor, often born from the most unusual corners of the mind.

Last updated:

Review Summary

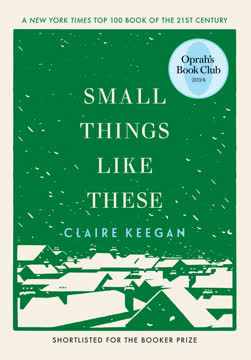

When We Cease to Understand the World blends fact and fiction to explore the lives of scientists and mathematicians who made groundbreaking discoveries. Readers praise Labatut's masterful writing and ability to make complex scientific concepts accessible. The book examines the dark side of scientific progress and the fine line between genius and madness. While some critics find the fictional elements problematic, many appreciate the unique approach to storytelling. The work is lauded for its thought-provoking nature and has been shortlisted for prestigious literary awards.