Key Takeaways

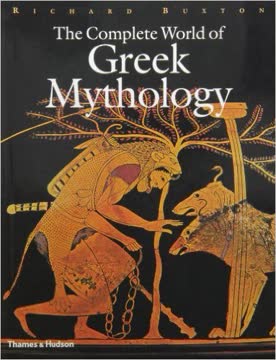

1. Greek Myths: Socially Powerful, Fluid Narratives

‘A myth is a socially powerful traditional story.’

Defining myth. Greek myths are narratives transmitted across generations, embodying and exploring the values of social groups and entire communities. Unlike simple misconceptions, they possess imaginative richness and profound social significance, shaping collective consciousness. Modern examples like Cuchulain or Frankenstein's monster demonstrate this enduring power.

Plurality and adaptation. A central characteristic of Greek myths is their inherent plurality; there was no single, canonical version of any tale. Each storyteller remade tradition to suit specific social and artistic contexts, allowing for constant invention and originality within intangible limits. This chameleon-like capacity for adaptation has been crucial to their survival and influence.

Diverse sources. Our understanding of Greek myths comes from a rich array of sources, both textual and visual.

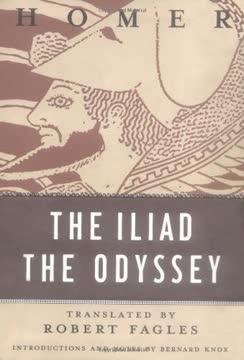

- Texts: Homer, Hesiod, tragedians (Aischylos, Sophokles, Euripides), lyric poets (Pindar), historians (Herodotos, Thucydides), and philosophers (Plato, Aristotle).

- Visuals: Sculptures, wall-paintings, mosaics, vase-paintings, coins, engraved gems, and decorated mirrors. These images often captured the richness and power of the stories, sometimes offering unique interpretations.

2. Origins: From Cosmic Chaos to Human Races

At the beginning of everything there was Chaos; this does not mean ‘Disorder’, but rather ‘Chasm’, in the sense of a dark, gaping space.

Cosmic beginnings. Hesiod's Theogony describes the universe's origin from Chaos, Gaia (Earth), and Eros (Sexual Love), followed by the emergence of Erebos, Night, Ouranos (Sky), Mountains, and Pontos (Sea). This initial phase is marked by violent struggles for succession among primordial deities. Ouranos, who prevented his offspring from emerging, was castrated by his son Kronos, leading to the birth of Aphrodite from his severed genitals.

Divine succession. Kronos, fearing overthrow, swallowed his own children, but Zeus was saved by Rheia, who tricked Kronos with a stone. Zeus eventually forced Kronos to vomit his siblings, establishing the Olympian order after a cosmic battle against the Titans and the monstrous Typhoeus. Zeus consolidated his power through strategic marriages and the birth of key Olympians like Athene (from his head) and Apollo.

Humanity's genesis. Greek myths also explored the origins of humankind, often through tales of decline or divine intervention.

- Five Races: Hesiod's Works and Days describes a decline from a Golden Race (under Kronos) to Silver, Bronze, Heroes, and finally, the present Iron Race, each progressively worse.

- Prometheus: The Titan Prometheus created humans from earth and water, and stole fire for them, enabling rituals like animal sacrifice.

- Pandora: As punishment for Prometheus's defiance, Zeus sent Pandora, the first woman, whose opening of a jar released evils into the world, leaving only Hope behind.

- The Flood: Deukalion and Pyrrha survived a great flood, repopulating the earth by throwing stones over their shoulders, which became men and women.

3. The Olympians: Flawed, Powerful, and Interconnected

There is a tension at the heart of the portrayal of the father of the gods, for he can be thought of as simultaneously the source of right and the source of everything.

Zeus: Sovereign and morally complex. Zeus, the sky god, wields terrifying power through thunderbolts and is symbolized by the eagle and sceptre. He is the "father of gods and men," heading the Olympian family. Despite being the source of justice (Dike, Themis), his personal conduct often defies human morality, marked by incest and serial adultery. His power, though immense, is not absolute, as seen when he bows to fate regarding his son Sarpedon's death.

Hera: Queen of marriage and vengeance. As Zeus's sister and consort, Hera is the goddess of marriage, worshipped in cults that celebrate the transition from virgin to bride. However, her mythological role is largely defined by her relentless jealousy and vindictiveness towards Zeus's numerous lovers and their offspring, most notably Io, Semele, and Herakles. Her persecutions often lead to tragic outcomes for mortals.

Diverse divine powers. The other Olympians each command distinct spheres of influence:

- Poseidon: Rules the sea, earthquakes, and horses, wielding his trident with both serene authority and explosive violence.

- Demeter: Goddess of corn and fertility, profoundly linked to motherhood through the myth of Persephone's abduction.

- Apollo: Embodies youthful beauty, music, prophecy, healing, and purification, often associated with harmonious order but capable of lethal fury.

- Artemis: Virgin huntress, mistress of wild animals, and protector of young people, yet demands sacrifice if her honor is threatened.

- Athene: Wise, resourceful, and valiant warrior goddess, born fully armed from Zeus's head, patron of craftsmanship and cities like Athens.

- Hermes: Divine messenger, guide of souls, and trickster, adept at crossing boundaries between worlds and states.

- Dionysos: God of ecstasy, wine, and wild nature, bringing both delight and dangerous madness, often accompanied by maenads and satyrs.

4. Heroes: Testing Humanity's Limits through Quests and Combat

What characterizes the heroic mortals of Greek mythology is not any virtue which they may have – one should therefore avoid any analogy with ‘saints’ – but rather the conspicuousness and sometimes outrageousness of what they do and suffer.

Heroic archetypes. Greek heroes are extraordinary mortals who push the boundaries of human potential, achieving great successes and enduring profound disasters. Their stories often follow patterns of arduous quests for precious prizes or combat against terrifying, monstrous opponents, frequently with divine intervention.

Perseus's quest. Perseus, son of Zeus and Danae, survived early persecution, set adrift in a chest. He embarked on a quest for the head of Medusa, one of the monstrous Gorgons whose gaze turned men to stone. Aided by Hermes and Athene, and equipped with magical items like winged sandals and a cap of invisibility, he successfully decapitated Medusa by viewing her reflection. He later rescued Andromeda from a sea monster and accidentally fulfilled the oracle predicting he would kill his grandfather, Akrisios.

Herakles's labors. Herakles, Zeus's son, was relentlessly persecuted by Hera, yet displayed immense strength from infancy. His most famous feats were the Twelve Labors, imposed by the weaker Eurystheus as expiation for a fit of madness:

- Slaying the Nemean Lion and Lernaean Hydra.

- Capturing the Keryneian Hind and Erymanthian Boar.

- Cleansing the Augeian Stables and driving away Stymphalian Birds.

- Capturing the Cretan Bull and Mares of Diomedes.

- Obtaining the Belt of Hippolyte and Cattle of Geryon.

- Picking the Apples of the Hesperides and fetching Kerberos from the Underworld.

Despite his triumphs, Herakles's life was marked by personal tragedy, including killing his own family, before his eventual apotheosis to Olympos.

5. Family Sagas: Extreme Paradigms of Human Bonds and Conflicts

The extreme nature of the myth’s narrative pushes us ever further, until we can no longer imagine where it will all end.

Themes of domestic drama. Greek family myths explore intense themes of honor, sexual jealousy, and power struggles, often leading to catastrophic outcomes. They highlight conflicts between:

- Irreconcilable parental demands on children (e.g., Orestes).

- Kin allegiance versus civic duty (e.g., Antigone).

- A woman's loyalty to father versus husband/lover (e.g., Ariadne, Medea).

These stories magnify everyday pressures into extreme, unforgettable narratives.

The House of Pelops. This lineage is cursed by a cycle of violence and transgression, beginning with Tantalos's crime of serving his son Pelops to the gods. Pelops's own deceit in winning Hippodameia led to Myrtilos's curse. His sons, Atreus and Thyestes, engaged in a bitter power struggle over Mycenae, culminating in Atreus serving Thyestes his own children. This act set the stage for Agamemnon's murder by his wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aigisthos, a revenge for Agamemnon's sacrifice of their daughter Iphigeneia.

The House of Laios. The Theban royal house is similarly plagued by fate and transgression. Laios's abduction of Pelops's son Chrysippos brought a curse that his own child would kill him. Despite attempts to avert it, Oedipus unknowingly fulfilled this prophecy by slaying Laios at a crossroads and then marrying his mother Jocasta after solving the Sphinx's riddle. Upon discovering the truth, Oedipus blinded himself, and Jocasta committed suicide. His sons, Eteokles and Polyneikes, died in a mutual duel for Thebes, leading to Antigone's tragic defiance of Kreon's burial edict.

6. Mythical Landscape: Sacred Spaces Shaping Narrative

The landscape was a blend of the natural and the cultural.

Mountains: Divine abodes and mortal encounters. Mountains in Greek mythology are sacred spaces, often serving as homes for gods (Olympos) or sites of divine births (Zeus on Dikte/Ida, Hermes on Kyllene). They are also places where mortals encounter the divine, often with dire consequences, such as Aktaion being torn apart by his hounds on Kithairon for disturbing Artemis. Mount Pelion, however, was a benign place where heroes like Achilles were educated by the Centaur Cheiron.

Caves: Primitive, sacred, and secluded. Caves are pervasive features, symbolizing wildness, primitive origins, and access to the sacred. They were sites of worship for Nymphs and Pan, and places where infant gods like Zeus and Dionysos were nurtured. Odysseus's journey features various caves: Kalypso's idyllic but confining grotto, Polyphemos's savage lair, and the Nymphs' cave on Ithaca, which marked his true homecoming.

Rivers and springs: Life-giving divinities. Fresh water sources were vital and often personified as divinities. Rivers, typically male, provided seminal energy and sired nymphs, while springs, usually female, embodied refreshing allure. The river-god Acheloös, known for his shape-shifting, wrestled Herakles. Genealogies frequently link communities to river-gods, emphasizing their foundational importance. Nymphs like Daphne, pursued by Apollo, transformed into a laurel tree, while Arethousa fled the river-god Alpheios across the sea to become a spring in Sicily.

7. The Underworld: A Realm of Varied Post-Mortem Fates

The stories [muthos] that are told of the world of Hades, and of how a man who has done wrong here must be punished there, though he may have ridiculed these stories hitherto, then indeed torment his soul in case there may be some truth in them.

Homer's gloomy Hades. In the Odyssey, Odysseus journeys to the dark, gloomy edge of the world, where he summons the shades of the dead by sacrificing animals. These insubstantial souls temporarily regain speech by drinking blood. Achilles famously laments his fate, preferring servitude in life to kingship in death. Notable transgressors like Tityos, Tantalos, and Sisyphos endure eternal, exemplary punishments for crimes against divine honor, often overseen by Minos as a judge.

Aristophanes' comic Afterlife. A stark contrast to Homer's somber vision is Aristophanes' Frogs, a riotous farce where Dionysos travels to Hades. Here, the Underworld features a cantankerous ferryman Charon, a shape-shifting monster Empousa, and joyful Initiates who enjoy a flower-strewn paradise. Aiakos, usually a judge of the dead, appears as an exaggerated, blustering doorkeeper.

Rivers of the dead and varied destinies. The Underworld is traversed by mythical rivers:

- Lethe: Caused oblivion in the dead.

- Styx: "Hatefulness," a sacred river by which gods swore oaths, with a real-world counterpart in Arcadia.

- Acheron: "Groaning," the river ferried by Charon, also with a real-world location in northwest Greece near the Nekyomanteion (Oracle of the Dead).

Post-mortem fates varied: favored heroes like Menelaos and Helen might go to the paradisiacal Elysian Fields or Isles of the Blessed, while the wicked were confined to Tartaros, a deep abyss of eternal punishment.

8. The Trojan War: A Crucible for Human and Divine Drama

The conflict between Greeks and Trojans remained the definitive mythical crucible in which to examine the significance of humanity’s place in the world.

Historicity and shifting perspectives. For ancient Greeks, the Trojan War was a historical event, precisely dated on inscriptions like the Parian Marble. Historians like Thucydides and Pausanias rationalized Homer's accounts, but never doubted the war's occurrence. While Homer presented Greeks and Trojans with even-handedness, later Athenian myth-tellers, especially after the Persian Wars, demonized Trojans as "barbarians" to serve political ideologies.

Troy's mythical foundations. The city of Troy (Ilion) was founded by Dardanos and later Ilos, with its walls built by Apollo and Poseidon. King Laomedon's betrayal of the gods led to Herakles sacking the city. Priam, Laomedon's son, ruled during the war. His wife Hekabe's dream of a firebrand led to the exposure of their son Paris, who, upon returning, caused the war by choosing Aphrodite in the Judgment of Paris and abducting Helen.

The war's unfolding. The Greek expedition, assembled under Agamemnon, faced delays and omens, including the sacrifice of Iphigeneia to appease Artemis. The Iliad focuses on Achilles's wrath, his withdrawal from battle, Patroklos's death, and Achilles's vengeful return, culminating in his duel with Hektor and Priam's plea for his son's body. After Achilles's death, Odysseus's cunning became paramount, leading to the theft of the Palladion and the stratagem of the Wooden Horse. The sack of Troy was marked by brutal acts against the Trojan royal family, including the deaths of Astyanax and Polyxena, and Aias's rape of Cassandra.

9. Odysseus' Nostos: A Journey of Wiles and Endurance

His awe-inspiring journey back to Ithaca was in some ways comparable with the voyage of the Argo, yet differed from it in crucial respects: its focus was not a vessel, but an individual man, and the objective was not a far-off, golden treasure, but simply the prize of going home.

A hero's arduous return. Odysseus, known for his crafty intelligence, initially feigned madness to avoid the Trojan War, which an oracle predicted would lead to a twenty-year absence. His journey home, or nostos, is a central narrative of endurance and cunning, detailed in Homer's Odyssey with a complex, non-linear chronology.

Encounters with the strange. After leaving Troy, Odysseus and his men faced numerous perils:

- Kikonians: Their imprudence led to losses.

- Lotus Eaters: Their fruit caused forgetfulness of home.

- Polyphemos: The one-eyed Cyclops, blinded by Odysseus's cunning, invoked Poseidon's wrath.

- Aiolos: God of winds, whose gift was squandered by the crew's curiosity.

- Laistrygonians: Giant cannibals who destroyed all but Odysseus's ship.

- Circe: The enchantress who turned men into swine, overcome by Odysseus with Hermes's help.

These encounters tested Odysseus's leadership and resourcefulness.

The final leg home. Odysseus's journey included a visit to the Underworld, where he consulted the seer Teiresias and spoke with the shades of Achilles and Agamemnon. He then navigated past the alluring Sirens, the monstrous Skylla and Charybdis, and endured the crew's transgression of eating Helios's sacred cattle, leading to their demise. Detained by Kalypso, he eventually rejected immortality for his longed-for home. Finally, conveyed by the Phaeacians, he returned to Ithaca in disguise, meticulously planned his vengeance against the suitors, and reunited with his loyal wife Penelope and father Laertes, restoring order to his household.

10. Myth's Enduring Pluralism and Adaptability

The tradition of Greek mythology will only survive if it never stops adapting to new needs, and, by adapting, continues to stimulate, to unsettle and to inspire.

Fluidity and reinterpretation. Greek mythology is characterized by its inherent fluidity, lacking a fixed orthodoxy. Myths were constantly reinterpreted and adapted across different authors, genres, historical periods, and geographical localities. For instance, Aphrodite's parentage varies between Homer (Zeus and Dione) and Hesiod (Ouranos's castration), demonstrating how narratives were shaped to emphasize different aspects of her divine nature.

Political and social utility. Myths served as flexible frameworks for exploring and asserting social and political values. Athenian myth-tellers, for example, used the figure of Theseus to embody their city's ideals of justice and hospitality, even manipulating genealogies to assert Athenian autochthony over Dorian claims. This adaptability allowed myths to remain relevant and powerful in changing cultural contexts.

Chameleon-like survival. The "chameleon-like capacity for adaptation" is key to the myths' survival. From their ancient Greek origins, they were re-imagined by the Romans, reinterpreted allegorically in the Middle Ages to fit Christian frameworks, and continually renewed by artists and writers from the Renaissance to the present day. This ongoing process of adaptation ensures their continued stimulation and inspiration across diverse cultures and eras.

11. From Greece to Global Influence: Myth's Constant Rebirth

It is in Roman clothing, and from Roman myth-tellers, that the modern world has inherited its ‘Greek’ mythology.

Roman appropriation and transformation. Greek myths profoundly influenced Roman civilization, with early evidence found in Etruria and Rome. Romans established "equivalences" between Greek and Roman deities (e.g., Zeus/Jupiter, Ares/Mars), often imbuing them with distinct Roman emphases. Roman poets like Plautus, Catullus, Virgil (Aeneid), and Ovid (Metamorphoses) masterfully re-imagined these tales, making them central to Roman identity and literature, effectively transmitting "Greek" mythology in a Roman guise to later generations.

Christian reinterpretation. The rise of Christianity challenged pagan myths, with early apologists like Clement of Alexandria and Lactantius ridiculing their immorality and absurdity. However, allegorical interpretations (e.g., Bishop Fulgentius, Ovide moralisé) transformed myths into moral lessons or cosmic symbols, making them acceptable within a Christian framework. Euhemerism, the belief that gods were deified mortals, also helped integrate pagan figures into Christian chronology.

Modern renewal. From the Renaissance onwards, classical myths experienced a "rebirth," dominating European art and literature. Artists like Botticelli and Titian explored their sensuality, while writers like Shakespeare and Milton drew deep inspiration. The German Romantics (Goethe, Schiller, Nietzsche) saw in them intense life, while Victorian moralists (Kingsley) used them for ethical instruction. In the 20th century, anthropology (Harrison, Frazer) and psychology (Freud's Oedipus Complex) offered new lenses, leading to diverse adaptations in theatre, film, and literature, ensuring their continued relevance.

12. The Interplay of Myth and Ritual

In the case of many rituals, we can point to myths which in some sense ‘went with’ the action dramatized in the ceremony.

Symbiotic relationship. Greek myths and rituals were deeply intertwined, each providing context and meaning for the other. Rituals often dramatized or commemorated events narrated in myths, while myths could explain the origins or significance of ritual practices. This dynamic interplay highlights how the Greeks integrated the sacred into their daily lives.

Rituals reflecting myths. Numerous examples illustrate this connection:

- Eleusinian Mysteries: The myth of Persephone's abduction and return mirrored the initiatory experience of death and rebirth.

- Kronia festival: Celebrated a topsy-turvy world, reflecting the myth of Kronos's chaotic rule before Zeus.

- Lemnian women: Their ritual of extinguishing and rekindling fire resonated with the Argonauts' visit and their role in regeneration.

- Lykaon cult: The myth of Lykaon's transformation into a wolf after human sacrifice was linked to initiation rites on Mount Lykaion.

- Hero cults: Worship at the burial sites of heroes like Pelops concentrated their enduring power, reinforcing their mythical significance.

Myths explaining rituals. Conversely, myths often provided etiological explanations for rituals or cultural practices. The story of Prometheus's trickery at Mekone, for instance, explained the division of sacrificial spoils between gods and mortals. The pervasive nature of this myth-ritual complex demonstrates that Greek religion was not merely a set of beliefs, but a lived experience, where stories and actions mutually reinforced a profound understanding of the world.

Last updated:

Review Summary

The Complete World of Greek Mythology receives overwhelmingly positive reviews with a 4.23/5 rating. Readers praise its accessibility, beautiful pictures, and comprehensive coverage of Greek myths, deities, heroes, and monsters. Many found it excellent for students and researchers, noting its well-organized format and contextual approach. Some reviewers appreciated its entertainment value and informative content. Common criticisms include bare-bones storytelling, lack of depth in myth variations, and textbook-like writing style. Several readers desired more detailed narratives rather than overview summaries. Despite minor shortcomings, most recommend it as an engaging introduction to Greek mythology.