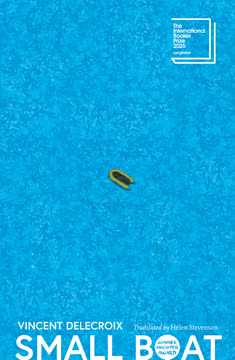

Plot Summary

Nightfall on the Channel

Under the cover of darkness, a group of migrants—Kurds, Africans, women, and a little girl—gather on a French beach, preparing to cross the Channel in a flimsy inflatable boat. They are strangers, united only by hope and desperation, each carrying the weight of their pasts and the uncertain promise of a future in England. The traffickers, indifferent and ignorant of the sea's dangers, send them off and disappear. The sea is calm but ominous, the sky starless, and the boat overloaded. As the engine sputters and the boat struggles, the migrants' anxiety grows. The journey is fraught with silence, fear, and the unspoken knowledge that the sea is both a barrier and a grave.

Voices in the Dark

As the boat drifts further from shore, the engine fails, and the migrants are left at the mercy of the waves. In the darkness, they use their phones to call for help, first the British, then the French rescue services. Communication is hampered by language barriers, poor signals, and the cold. The young man at the front becomes the voice of the group, relaying their desperate situation. The responses from authorities are procedural, detached, and increasingly frustrating. The migrants' fear intensifies as the boat begins to take on water, and the night seems endless, filled with the sound of waves and the rising panic of those on board.

The Call for Help

The migrants' calls for help are met with requests for geolocation and reassurances that help is coming. The French and British authorities debate jurisdiction, each reluctant to take responsibility as the boat drifts between their waters. The migrants, cold and wet, cling to hope as they wait for rescue that never arrives. The young man calls repeatedly, his pleas growing more urgent as the situation deteriorates. The official voices on the other end remain calm, almost mechanical, their empathy dulled by routine and the sheer volume of such emergencies. The migrants' fate hangs in the balance, suspended between two nations and the indifferent sea.

Boundaries and Blame

As the boat crosses from French to British waters, the responsibility for rescue shifts. The authorities on both sides cite rules and protocols, each deferring action to the other. The migrants, unaware of these invisible boundaries, continue to plead for help. The sea, meanwhile, knows no borders. The bureaucratic dance of blame and avoidance becomes a silent accomplice to tragedy. The official logs record the incident as "rescued," even as bodies later wash ashore. The question of who is to blame—individuals, institutions, or the system itself—remains unresolved, lost in the fog of procedure and moral ambiguity.

The Interrogation Begins

In the aftermath, the narrative shifts to the perspective of the French radio operator at Cap Gris-Nez, now under investigation. She is confronted by a police inspector—a woman who eerily resembles her—who plays back the recordings of that night. The operator is forced to relive her words, her tone, and her decisions. The interrogation is not just legal but moral, probing the boundaries between professional detachment and human empathy. The operator insists she was following protocol, trained to treat all distress calls equally, without judgment or emotion. Yet the inspector presses her to confront the deeper implications of her actions and inactions.

Mirror of Responsibility

The operator sees herself in the inspector, both literally and figuratively. Their similarities—appearance, demeanor, even their professional detachment—create a sense of being judged by a mirror image. The interrogation becomes an internal dialogue about guilt, responsibility, and the nature of moral failure. The operator questions whether she could have done more, or whether the system itself is designed to produce such outcomes. She is haunted by the phrase, "You will not be saved," uttered in a moment of frustration, now echoing as a possible condemnation of herself and society at large.

The Sinking Boat

Back on the boat, the situation becomes dire. The inflatable tubes deflate, water rises, and panic spreads. Some fall into the sea, clinging desperately to the wreckage. The young man continues to call for help, but the responses grow shorter, more perfunctory. The cold numbs their bodies and minds; hope fades with each passing minute. A cargo ship appears, its searchlight sweeping the water, but it does not stop. The migrants are left to the mercy of the elements, their final moments marked by exhaustion, resignation, and the slow, silent approach of death.

Bureaucracy and the Abyss

The aftermath is a tangle of investigations, reports, and public outrage. The French and British authorities each point to the other's failures. The operator is suspended, her actions scrutinized in minute detail. The inquiry becomes less about finding truth and more about assigning blame, protecting reputations, and maintaining the illusion of order. The operator reflects on the machinery of bureaucracy, which demands detachment and efficiency but is quick to scapegoat individuals when tragedy strikes. The abyss is not just the sea, but the moral void at the heart of the system.

The Weight of Words

The operator's words—recorded, replayed, dissected—become the focal point of the investigation. Did she say the right things? Was her tone appropriate? The distinction between action and speech blurs; her failure is measured not just by what she did, but by what she said and how she said it. The expectation that she should have offered comfort, even if it was a lie, becomes a new standard of humanity. The operator resists this demand, insisting that empathy is a luxury she cannot afford in her role. Yet she is haunted by the possibility that words alone can condemn or absolve.

The Sea's Indifference

The sea is a constant presence—beautiful, ancient, and utterly indifferent. The operator, once in love with the sea, now sees it as a monstrous force, glutted with the bodies of the drowned. The sea becomes a symbol of evil, chaos, and the limits of human agency. It is both the literal cause of death and a metaphor for the world's indifference to suffering. The operator's daily runs along the shore, her memories of childhood, and her reflections on the sea's power all reinforce the sense that some forces are beyond control or comprehension.

Survivors and Spectators

The narrative expands to include not just the direct participants but the wider world—the spectators on the shore, the public watching from a distance, the media, and the readers themselves. The operator argues that there is no shipwreck without spectators, that everyone is implicated by their inaction or indifference. The survivors, too, are haunted by what they have witnessed and endured. The line between victim and bystander blurs, raising uncomfortable questions about collective responsibility and the limits of empathy.

The Monster Within

The operator is accused of lacking empathy, of being a "monster." She rejects this label, arguing that her detachment is a professional necessity, not a moral failing. Yet she is forced to confront the possibility that the system itself produces monsters—ordinary people who, through routine and repetition, become numb to suffering. The investigation becomes a search for the origins of inhumanity, whether in personal trauma, institutional culture, or the demands of the job. The operator's struggle to define herself against these accusations is both a defense and an admission of vulnerability.

The Question of Justice

The survivors and the dead seem to demand justice, but what form can it take? The operator is haunted by the idea that saving some while others die is inherently unjust, that every act of rescue is shadowed by those who are left behind. The legal inquiry seeks to assign blame, but the deeper question is whether justice is even possible in a world where suffering is so widespread and arbitrary. The operator's reflections on justice, guilt, and the impossibility of saving everyone reveal the tragic limitations of human agency.

The Shoreline of Guilt

The operator's sense of guilt is both personal and universal. She feels the weight of her own actions, but also recognizes that she is part of a larger system—one that implicates everyone who watches, judges, or turns away. The shoreline becomes a metaphor for the boundary between action and inaction, between those who drown and those who survive. The operator's internal struggle mirrors the broader societal reluctance to confront uncomfortable truths about migration, responsibility, and the value of human life.

The Drowned and the Living

The dead do not simply vanish; they linger in memory, in dreams, and in the collective conscience. The operator imagines the drowned walking on the sea bed, joined by others lost to the waves. Her daughter, Léa, offers a child's hope that perhaps the lost are not truly gone. The narrative blurs the line between reality and imagination, between mourning and myth. The living are haunted by the dead, and the act of remembering becomes both a burden and a form of resistance against forgetting.

The Circle of Innocence

The operator reflects on the impossibility of proving innocence in a world where everyone is, in some sense, guilty. The legal presumption of innocence is revealed as a comforting illusion, masking the deeper reality that all are complicit in the suffering of others. The investigation circles endlessly, unable to resolve the fundamental questions of blame and responsibility. The operator's struggle to assert her innocence becomes a meditation on the human condition, where the boundaries between victim, perpetrator, and bystander are always shifting.

The Voice of All

In the end, the operator's voice is not just her own, but that of everyone who witnesses suffering and does nothing. Her words—"You will not be saved"—become a collective admission of failure, a recognition that the world's indifference is shared by all. The narrative closes with the operator standing on the shore, shouting into the wind, her voice carrying the weight of all those who watch but do not act. The tragedy is not just the loss of life, but the loss of the illusion that anyone is truly innocent.

No One Is Saved

The story ends not with resolution, but with the recognition that the cycle of suffering, blame, and inaction continues. The operator, the survivors, the dead, and the spectators are all caught in the same web. The sea remains, vast and indifferent, swallowing the hopes and lives of those who dare to cross it. The final message is stark: in a world where boundaries, bureaucracy, and indifference prevail, no one is truly saved—not the migrants, not the rescuers, not the spectators. The tragedy is not just an event, but a condition of modern existence.

Characters

The Radio Operator (Narrator)

The unnamed French radio operator is the novel's central consciousness, a woman trained to respond to maritime emergencies with detachment and efficiency. She is a single mother, balancing her demanding job with caring for her daughter, Léa. Her psyche is marked by exhaustion, self-doubt, and a growing sense of alienation from both her work and her own emotions. The operator's journey is one of self-interrogation: she is forced to confront the gap between her professional role and her moral responsibilities, especially after her words and actions are scrutinized in the wake of the tragedy. Her development is a descent into self-examination, as she questions not only her own culpability but the very nature of empathy, responsibility, and humanity in a bureaucratic system.

The Police Inspector

The inspector is both a literal and figurative double for the operator—similar in appearance, demeanor, and professional detachment. She serves as the voice of societal judgment, pressing the operator to account for her actions and, more crucially, her apparent lack of empathy. The inspector's probing is not just legal but existential, forcing the operator to confront uncomfortable truths about herself and the system she serves. Their dynamic is fraught with tension, as the inspector oscillates between sympathy and condemnation, ultimately embodying the collective demand for accountability and the impossibility of true absolution.

The Young Migrant (Telephone Man)

The young man who repeatedly calls for help from the sinking boat becomes the human face of the tragedy. His pleas—urgent, persistent, and ultimately futile—are the emotional core of the narrative. He is both an individual and a stand-in for countless others who risk everything for a chance at a better life. His relationship to the operator is mediated by technology and bureaucracy, yet his voice pierces the narrative's detachment. His fate—drowning after hours of waiting—haunts the operator and serves as a constant reminder of the human cost of indifference.

Léa

Léa, the operator's young daughter, represents innocence and the possibility of redemption. Her presence grounds the operator, offering moments of tenderness and vulnerability amid the surrounding bleakness. Léa's questions and imaginings—her hope that the drowned might have survived, her concern for her mother—highlight the contrast between a child's empathy and the adult world's rationalizations. She is both a source of comfort and a mirror reflecting the operator's own lost innocence.

Julien

Julien, the operator's partner on night duty, embodies a different form of detachment—one that is intellectual, even performative. He distances himself from the suffering he witnesses by quoting philosophers and maintaining an air of ironic resignation. His attitude both irritates and reassures the operator, offering a model of how to survive emotionally in a job that demands constant exposure to tragedy. Julien's presence underscores the novel's exploration of coping mechanisms and the thin line between self-preservation and indifference.

Eric

Eric, Léa's father and the operator's ex-partner, is a background presence whose attitudes reflect the broader societal ambivalence toward migrants. He is openly hostile to the operator's work, questioning its value and cost, and urging her to leave the job. His relationship with the operator is strained, marked by mutual disappointment and conflicting values. Eric's views serve as a counterpoint to the operator's internal struggles, highlighting the prevalence of prejudice and the difficulty of maintaining compassion in a hostile environment.

The Survivors

The two migrants who survive the sinking are spectral figures, appearing at the narrative's end as both real people and symbols of endurance. Their survival is ambiguous—both a testament to human resilience and a reminder of the randomness of fate. They represent the ongoing demand for justice and recognition, haunting the operator and the society that failed them. Their presence blurs the line between the living and the dead, the saved and the lost.

The Drowned

The twenty-seven migrants who perish in the Channel are both individuals and a collective presence. Their deaths are the novel's central tragedy, but they also become symbols of all those lost to the sea, forgotten by history and bureaucracy. The operator imagines them walking on the sea bed, joined by others from past tragedies—a procession of the drowned that haunts the living. They embody the novel's themes of memory, mourning, and the impossibility of closure.

The Traffickers

The traffickers who organize the crossing are shadowy figures, motivated by profit and unconcerned with the migrants' fate. They represent the impersonal forces that drive people into danger, as well as the broader systems of exploitation and neglect that underpin the migration crisis. Their absence from the narrative's moral reckoning highlights the difficulty of assigning blame in a world where responsibility is diffuse and consequences are borne by the most vulnerable.

The Spectators

The novel's final, most unsettling character is the collective "we"—the spectators on the shore, the public, the readers. The operator insists that there is no shipwreck without spectators, implicating everyone in the tragedy. This diffuse character blurs the boundaries between individual and collective guilt, challenging the reader to confront their own role in systems of suffering and indifference.

Plot Devices

Dual Narrative Perspective

The novel alternates between the operator's introspective, often claustrophobic account of her interrogation and the harrowing, external perspective of the migrants' journey and demise. This structure creates a powerful juxtaposition between the detached, procedural world of bureaucracy and the visceral, immediate suffering of those at sea. The dual narrative heightens the emotional impact, forcing readers to inhabit both the position of the rescuer and the rescued, the judge and the judged.

The Mirror Motif

The operator's encounter with the inspector—her near-double—serves as a literal and metaphorical mirror, reflecting her own doubts, fears, and potential for inhumanity. This device blurs the line between self and other, guilt and innocence, and transforms the interrogation into an existential reckoning. The motif recurs throughout the novel, emphasizing the difficulty of escaping self-judgment and the universality of moral ambiguity.

Recorded Voices and Repetition

The repeated playback of the operator's recorded words, especially the phrase "You will not be saved," becomes a central plot device. The recordings serve as both evidence and accusation, forcing the operator—and the reader—to confront the gap between intention and effect, action and speech. The motif of repetition—of calls for help, official responses, and internal monologues—underscores the numbing effect of routine and the persistence of unresolved trauma.

Bureaucratic Fragmentation

The novel meticulously details the procedural steps, jurisdictional boundaries, and institutional evasions that shape the tragedy. This device exposes the ways in which systems designed to save lives can also enable neglect and dehumanization. The fragmentation of responsibility—between individuals, departments, and nations—becomes both a narrative technique and a thematic concern, highlighting the moral void at the heart of modern bureaucracy.

Symbolism of the Sea

The sea is more than a setting; it is a character, a symbol of chaos, evil, and the limits of human control. Its vastness and indifference dwarf the struggles of both migrants and rescuers, serving as a constant reminder of mortality and the fragility of hope. The sea's presence in the operator's daily life, memories, and nightmares reinforces the novel's exploration of trauma, guilt, and the search for meaning in the face of overwhelming loss.

Analysis

Vincent Delecroix's Small Boat is a searing meditation on responsibility, guilt, and the limits of empathy in the face of systemic tragedy. By weaving together the perspectives of a beleaguered rescue operator and the doomed migrants she fails to save, the novel exposes the moral ambiguities and bureaucratic evasions that define contemporary responses to migration crises. The operator's insistence on professional detachment—her refusal to offer false comfort or feigned empathy—becomes both a shield and a source of condemnation, raising uncomfortable questions about the nature of humanity in a world governed by rules, protocols, and shifting boundaries. The novel's relentless interrogation of innocence and blame implicates not just individuals, but institutions and societies, challenging readers to confront their own complicity as spectators. The sea, as both setting and symbol, embodies the indifference of nature and the abyss at the heart of modern life. Ultimately, Small Boat refuses easy answers or redemption, insisting that the tragedy of the drowned is not an isolated event but a condition of our shared existence—one in which no one is truly saved, and the voice of the operator becomes the voice of all.

Last updated: