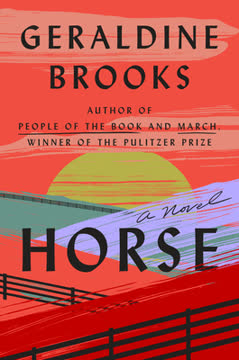

Plot Summary

Clouds Over Virginia

Chaplain March, the absent father from Little Women, writes home from the front lines of the Civil War, determined to shield his wife and daughters from the brutal realities he witnesses. The narrative opens with March's poetic letters, which mask the carnage and chaos of battle. He is quickly disillusioned by the violence and suffering around him, realizing that his ideals are no match for the grim truths of war. The Battle of Ball's Bluff is a turning point, as March is forced to confront his own helplessness and the limits of his faith. The trauma of watching men die, and his own narrow escape, begin to erode his sense of purpose and certainty.

The Peddler's Awakening

Years before the war, a young, idealistic March travels the South as a peddler, eager to trade books and notions. He is welcomed into the home of the Clements, a wealthy plantation family, where he is captivated by their cultured world and the beautiful, literate slave, Grace. March's initial blindness to the realities of slavery is shattered when he witnesses the brutal punishment of Grace for a minor transgression—a whipping he inadvertently causes. This experience plants the seeds of guilt and a lifelong commitment to abolition, but also leaves him with a deep, unresolved shame for his complicity and inaction.

Grace and the Whip

March's relationship with Grace deepens, marked by mutual respect, intellectual kinship, and a forbidden, fleeting intimacy. When their secret lessons for a slave child are discovered, Grace is whipped in front of March and the entire plantation. The trauma of this event haunts March, who is powerless to intervene. Grace's dignity in the face of suffering and her later forgiveness become a touchstone for March's understanding of moral courage and the complexities of human bondage. This episode cements his sense of responsibility and his lifelong struggle with guilt.

Letters Home, Truths Withheld

Throughout his service, March writes daily to his wife, Marmee, and their daughters, crafting letters that are lyrical and loving but omit the horrors he endures. He rationalizes this as protection, but the gap between his words and reality grows. The letters become a device for self-censorship and emotional distance, as March struggles with the burden of leadership, the suffering of soldiers, and his own failures. His inability to share the truth with Marmee foreshadows the emotional chasm that will later threaten their marriage.

Marmee's Fire

Back in Concord, Marmee manages the household and their four daughters with fierce love and a volatile temper. Her commitment to abolition and justice is as strong as March's, but she is often frustrated by the constraints of her gender and the sacrifices demanded by her husband's ideals. The family's financial ruin—caused by March's support of John Brown and failed utopian ventures—forces Marmee and the girls into poverty and work. Marmee's struggle for self-mastery and her outbursts of anger reveal the costs of principle and the emotional toll of war on those left behind.

The Cost of Ideals

March's unwavering commitment to abolition and nonviolence brings both moral authority and personal disaster. His financial support of John Brown's radicalism leads to the family's ruin, and his refusal to compromise his beliefs isolates him from fellow soldiers and superiors. As a chaplain, he is often at odds with the army's pragmatism and the racism of his peers. His idealism is tested by the realities of war, the suffering of black refugees, and his own inability to effect meaningful change. The narrative explores the tension between moral purity and practical action.

Oak Landing's Experiment

March is reassigned to Oak Landing, a former plantation now run as a "free labor" experiment by a young Northern entrepreneur, Canning. March is tasked with educating the freed slaves, but quickly discovers that emancipation has not brought justice or dignity. The workers are overworked, underfed, and still subject to arbitrary punishment. Canning's good intentions are undermined by economic desperation and ingrained prejudice. March's efforts to teach and uplift are met with both hope and frustration, as the experiment teeters between progress and collapse.

Lessons in Freedom

March's school becomes a sanctuary for the plantation's children and adults, who hunger for literacy and self-determination. He is inspired by their resilience and intelligence, especially the mute girl Zannah and her son Jimse. Yet, the shadow of violence and betrayal looms. March's attempts to protect and empower his students are constantly threatened by disease, hunger, and the ever-present danger of Confederate raids. The chapter highlights the transformative power of education, but also the fragility of hope in a world still ruled by force.

Harvest and Betrayal

After months of toil, the plantation's first paid harvest is celebrated with joy and a sense of accomplishment. The freed people, for the first time, receive wages and a taste of autonomy. Yet, this fragile victory is short-lived. The withdrawal of Union protection and the return of Confederate guerrillas expose the experiment's vulnerability. Betrayal from within—by Zeke, a trusted worker—leads to the plantation's destruction. March's sense of failure and guilt deepens as he witnesses the collapse of everything he and the freed people have built.

The Red Moon Raid

Under the cover of the "red moon," Confederate raiders attack Oak Landing, burning fields, killing loyal workers, and capturing many of the freed people. March, paralyzed by fear, hides while others are tortured and murdered. His cowardice in this moment becomes a source of lifelong shame. He and Jesse, a former slave, attempt a desperate rescue, but are only partially successful. The violence culminates in the deaths of Canning, the child Jimse, and others. March is gravely wounded and left for dead, saved only by Zannah's courage.

Guilt and Grace

March is rescued by Zannah, who brings him to Union lines at great personal risk. He is transported, feverish and near death, to a Washington hospital. Haunted by guilt over his failures—his inability to save others, his moment of cowardice, his emotional betrayal of Marmee—March is consumed by self-loathing. The memory of Grace, and her example of forgiveness, becomes both a torment and a possible path to redemption. The chapter explores the limits of atonement and the possibility of grace in the aftermath of trauma.

Marmee's Vigil

When March's illness becomes dire, Marmee travels to Washington, accompanied by Mr. Brooke. She finds her husband emaciated, delirious, and haunted by the war. Marmee's own anger and grief surface as she confronts the reality of what war has done to her family and her marriage. She is forced to navigate the squalor of wartime hospitals, the indifference of overworked nurses, and her own feelings of betrayal and inadequacy. Marmee's voice reveals the hidden costs of war for women and the emotional labor of holding a family together.

Truths Unveiled

Marmee discovers the depth of March's connection to Grace Clement, now a skilled nurse in Washington. Consumed by jealousy and suspicion, Marmee confronts Grace, who reveals the truth of her past with March and her own burdens of guilt and survival. The encounter forces Marmee to reckon with the complexities of love, fidelity, and forgiveness. Both women are changed by their conversation, gaining a deeper understanding of each other and of March's struggles. The chapter explores the possibility of reconciliation and the necessity of compassion.

Reconstruction of the Heart

As March slowly recovers, he and Marmee must rebuild their relationship in the aftermath of war, betrayal, and loss. Both are scarred—physically, emotionally, and spiritually. Through honest conversation and mutual vulnerability, they begin to forgive each other and themselves. March is urged by Grace to return home and focus on his family, rather than seeking redemption through further sacrifice. The couple's reconstruction is mirrored by the nation's, as they face the challenge of living with the consequences of their choices and the hope of renewal.

Homecoming Shadows

March returns to Concord, physically diminished and emotionally changed. The reunion with his daughters and Marmee is joyful but fraught with unspoken pain and the weight of memory. The family's embrace offers comfort, but March is haunted by the ghosts of those he could not save and the knowledge that innocence is lost. The novel ends with a sense of hard-won grace: the possibility of healing, the enduring power of love, and the acceptance that life, like the nation, must be rebuilt from the ruins of war.

Characters

March

March is the absent father from Little Women, reimagined as a complex, deeply principled man whose idealism is both his strength and his undoing. Raised in poverty, he becomes a self-taught intellectual, abolitionist, and Unitarian minister. His youthful naiveté is shattered by his experiences as a peddler in the South, where he witnesses the brutality of slavery and forms a lifelong bond—and guilt—with Grace. As a Civil War chaplain, March is driven by conscience but often paralyzed by self-doubt and the impossibility of living up to his ideals. His journey is one of disillusionment, guilt, and, ultimately, a search for grace and forgiveness. His relationships—with Marmee, Grace, and the freed people he tries to help—reveal his longing for moral purity and his struggle to accept his own limitations.

Marmee (Margaret March)

Marmee is March's wife and the mother of their four daughters. She is passionate, intelligent, and unafraid to speak her mind, but often struggles with her temper and the constraints of her role. Marmee's devotion to abolition and justice matches March's, but she is more pragmatic and attuned to the needs of her family. The war and March's absence force her into new roles—provider, disciplinarian, and emotional anchor. Her journey is one of self-mastery, resilience, and the painful work of forgiveness. Marmee's perspective reveals the hidden costs of war for women and the emotional complexity of marriage.

Grace Clement

Grace is a literate, enslaved woman on the Clement plantation, whose intelligence and poise captivate March. She endures unimaginable suffering with dignity, including a brutal whipping and later, sexual violence and loss. Grace's capacity for forgiveness and her refusal to be defined by victimhood make her a moral touchstone for March. As a nurse in Washington, she becomes a healer not only of bodies but of souls, guiding both March and Marmee toward understanding and grace. Her character embodies the resilience and agency of black women in the face of oppression.

Canning

Ethan Canning is the young Northern entrepreneur who leases Oak Landing as a free labor experiment. Ambitious but inexperienced, he is quickly overwhelmed by the realities of managing a plantation in wartime. His relationship with March is fraught—by turns adversarial and collegial—as both men struggle with the limits of their ideals. Canning's decline, both physical and moral, mirrors the collapse of the utopian project and the nation's struggle with emancipation.

Jesse

Jesse is a strong, intelligent former slave at Oak Landing, who becomes March's best student and a leader among the freed people. His mathematical aptitude and moral clarity make him a symbol of the potential unleashed by freedom. Jesse's loyalty and courage are tested by betrayal and violence, and his fate—recaptured and re-enslaved—underscores the precariousness of black autonomy during the war.

Zannah

Zannah is a young, mute woman at Oak Landing, whose son Jimse becomes the focus of March's affection and hope. Her silence is the result of a horrific act of violence, and her story embodies the suffering and endurance of enslaved women. Zannah's courage in saving March's life, and her loss of Jimse, highlight the personal costs of war and the limits of redemption.

Jimse

Jimse is Zannah's young son, a symbol of innocence and the future that emancipation promises. His eagerness to learn and his tragic death during the raid on Oak Landing represent the destruction of hope and the generational trauma inflicted by slavery and war.

Mr. Clement

Augustus Clement is the master of the plantation where March first encounters slavery. He is cultured and philosophical, yet rationalizes and perpetuates the system of bondage. His relationship with Grace and his eventual decline illustrate the moral rot at the heart of Southern gentility.

Aunt March

Aunt March is March's wealthy, judgmental aunt, whose offers of help are often barbed and conditional. She represents the social expectations and limitations placed on women and families, and her relationship with Marmee is a source of tension and eventual reconciliation.

Mr. Brooke

Mr. Brooke is the tutor to the Laurences and a friend to the March family. He accompanies Marmee to Washington and provides practical and emotional support. His own desire to serve in the war and his growing attachment to Meg add depth to his character as a man of quiet strength and evolving purpose.

Plot Devices

Epistolary Structure and Shifting Perspectives

The novel employs an epistolary structure, with March's letters home serving as both a narrative device and a symbol of self-censorship. The letters allow March to present an idealized version of himself and the war, while the narrative voice reveals the reality he cannot share. The shift to Marmee's perspective in the second half of the novel provides a counterpoint, exposing the emotional costs of silence and the necessity of honest communication. This duality deepens the psychological complexity of the characters and the story.

Flashbacks and Nonlinear Narrative

Brooks uses flashbacks to March's youth as a peddler and his early encounters with slavery to illuminate the origins of his ideals and guilt. The nonlinear structure allows the reader to see how past traumas and choices reverberate through the present, shaping March's actions and relationships. This device underscores the theme that history—personal and national—cannot be escaped, only confronted.

Foreshadowing and Irony

March's early confidence and moral certainty are repeatedly undercut by the realities he faces, a pattern foreshadowed in his initial blindness to the suffering around him. The irony of his efforts—meant to liberate and uplift—often resulting in unintended harm, highlights the limits of good intentions and the complexity of social change.

Symbolism

Recurring symbols—such as the locks of hair March carries, the red moon, and the ruined plantation—embody themes of memory, loss, and the possibility of renewal. The act of teaching, the schoolroom, and the written word symbolize both hope and the dangers of knowledge in a world built on oppression.

Analysis

March is a profound reimagining of the absent father from Little Women, transforming him from a symbol of virtue into a fully realized, flawed human being. Through March's journey—from naive idealist to haunted survivor—Brooks interrogates the limits of moral purity in a world riven by violence and injustice. The novel explores the psychological toll of war, the complexities of race and gender, and the ways in which good intentions can lead to unintended harm. By giving voice to Marmee and Grace, Brooks expands the narrative to include the often-silenced experiences of women and the enslaved, challenging the myth of redemptive suffering. Ultimately, March is a story of forgiveness—of others and of oneself—and the hard, ongoing work of rebuilding lives and relationships in the aftermath of trauma. It asks whether grace is possible in a broken world, and suggests that, while innocence may be lost, the struggle for justice and love endures.

Last updated:

FAQ

0. Synopsis & Basic Details

What is March about?

- Idealism meets brutal reality: March reimagines the absent father from Louisa May Alcott's Little Women, Mr. March, as a Union chaplain during the American Civil War. The novel follows his journey from an idealistic abolitionist to a man deeply scarred by the war's horrors, his own moral compromises, and the profound suffering he witnesses.

- A hidden past revealed: The narrative delves into March's youth as a peddler in the antebellum South, where a formative, forbidden relationship with an enslaved woman named Grace Clement shapes his abolitionist convictions and burdens him with lifelong guilt. This past intertwines with his wartime experiences, revealing the complex origins of his principles and his personal failures.

- War's toll on family: While March endures the physical and psychological devastation of the front lines, his wife, Marmee, and their daughters face their own struggles with poverty, societal expectations, and the emotional strain of his absence and the war's impact on their lives in Concord. The story explores the hidden costs of conflict, both on the battlefield and at home.

Why should I read March?

- Deepens a literary classic: For fans of Little Women, March offers a rich, complex, and often dark counter-narrative, filling in the untold story of a beloved but enigmatic character. It challenges the idealized portrayal of the March family, adding layers of moral ambiguity and human frailty.

- Unflinching historical realism: Geraldine Brooks provides a meticulously researched and unflinching portrayal of the Civil War, moving beyond romanticized notions to expose the brutal realities of combat, the complexities of emancipation, and the pervasive racism that permeated even the Union cause.

- Explores profound moral questions: The novel grapples with timeless themes of idealism versus pragmatism, the nature of courage and cowardice, the burden of guilt, and the possibility of redemption and forgiveness in the face of immense suffering and personal failure.

What is the background of March?

- Alcott family inspiration: The novel draws heavily from the life of A. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May Alcott's father, a transcendentalist philosopher, educator, and radical abolitionist. Brooks uses his journals and letters as a "scaffolding" to build March's character, incorporating his vegetarianism, utopian ideals, and complex relationship with John Brown.

- Civil War context: Set during the early years of the American Civil War (Brooks shifts the timeline of Little Women forward a year to 1861-1862), the story immerses readers in specific historical events like the Battle of Ball's Bluff, the Union's "contraband" policy, and the challenges of establishing "free labor" plantations in the occupied South.

- Exploration of abolitionism's nuances: The book delves into the varied and often contradictory facets of the abolitionist movement, from the pacifist Quakers to the violent radicalism of John Brown, and the pragmatic, sometimes cruel, realities of Union efforts to manage freed slaves.

What are the most memorable quotes in March?

- "I never promised I would write the truth.": This opening line from March's letter (Chapter 1) immediately establishes the novel's central theme of concealed reality and the burden of self-censorship, foreshadowing the emotional distance and lies that will plague his marriage and his internal life.

- "If you live with your head in the lion's mouth, it's best to stroke it some.": Grace Clement's poignant and pragmatic advice to March (Chapter 2) encapsulates the survival strategies of enslaved people, highlighting her profound wisdom and resilience in the face of overwhelming oppression, and March's naive idealism.

- "He has been dipped in the river of fire, Mrs. March. I am afraid that there may not be very much left of the man we knew.": Grace's stark assessment of March's psychological state to Marmee (Chapter 16) powerfully conveys the transformative and destructive impact of war and trauma, suggesting a profound, perhaps irreversible, loss of his former self.

What writing style, narrative choices, and literary techniques does Geraldine Brooks use?

- Dual narrative perspective: The novel primarily employs a first-person narrative from March's perspective, offering intimate access to his thoughts, struggles, and self-deception. A significant shift to Marmee's first-person voice in Part Two provides a crucial counterpoint, revealing the emotional toll of March's absence and the complexities of their marriage from her viewpoint.

- Rich sensory detail and historical immersion: Brooks's prose is highly descriptive, immersing the reader in the sights, sounds, and smells of the Civil War era—from the stench of field hospitals to the beauty of the Southern landscape and the squalor of Washington D.C. This meticulous detail grounds the historical fiction in a vivid, tangible reality.

- Intertextual dialogue and allusion: The novel is in constant conversation with Little Women, drawing characters and plot points while subverting expectations. Brooks also weaves in allusions to classical literature, philosophy, and historical figures (Emerson, Thoreau, John Brown), enriching the thematic depth and intellectual landscape of the story.

1. Hidden Details & Subtle Connections

What are some minor details that add significant meaning?

- The ambrotype of Marguerite Jamison: When March finds Canning's hidden personal effects, the ambrotype of a young, dark-haired girl (Chapter 12) reveals Canning's secret grief and motivation. This subtle detail humanizes the often-harsh Canning, showing his vulnerability and the personal losses that drive his relentless pursuit of profit, mirroring March's own hidden sorrows.

- March's physical reactions to trauma: Throughout the novel, March's body betrays his internal turmoil, from his "aching eye" and "tremor of exhaustion" after Ball's Bluff (Chapter 1) to his nausea at the smell of meat (Chapter 1) and his physical collapse from fever. These somatic responses subtly underscore the psychological weight of his experiences, demonstrating how deeply the war and his guilt affect him beyond mere mental distress.

- The "wooden nutmeg" anecdote: The story of the Connecticut peddler selling wooden nutmegs (Chapter 2) serves as a subtle commentary on Yankee cunning and the South's perception of Northern deceit. It foreshadows March's own initial naiveté and later, his complicity in a system he claims to oppose, highlighting the pervasive nature of deception and self-interest.

What are some subtle foreshadowing and callbacks?

- March's early aversion to meat: His childhood refusal to eat salt pork and his revulsion at the screams of slaughtered pigs (Chapter 1) foreshadow his later vegetarianism and deep-seated pacifism, linking his personal moral code to his early experiences with suffering and violence, long before the war.

- The recurring motif of "holes": From Jo's "hidey-hole" for runaways (Chapter 7) to March's "hiding hole" in the cotton seed (Chapter 12) and the well where Zeke was imprisoned (Chapter 6), these enclosed spaces subtly represent both sanctuary and confinement, safety and shame, reflecting the characters' attempts to escape or endure their circumstances.

- The "river of fire" metaphor: Grace's description of March being "dipped in the river of fire" (Chapter 16) is a powerful callback to his near-drowning in the Potomac after Ball's Bluff (Chapter 1). This recurring image symbolizes his traumatic immersion in the horrors of war and guilt, suggesting a baptism by fire that profoundly alters his spirit.

What are some unexpected character connections?

- March's indirect connection to John Brown's violence: March's financial support for Brown, initially intended for land speculation, is later revealed to have funded Brown's secret arms caches for insurrection (Chapter 7). This unexpected connection implicates March directly in the violence he morally abhors, deepening his guilt and challenging his pacifist ideals.

- Grace Clement's true parentage: The revelation that Grace is Mr. Clement's daughter (Chapter 3) and thus March's former lover's half-sister, adds a layer of tragic irony and complexity to their relationship. It underscores the pervasive sexual exploitation inherent in slavery and explains Grace's unique position and later, her profound, hidden trauma.

- Beth's quiet courage and Flora's story: Beth, the "Mouse" of the family, unexpectedly demonstrates immense courage by confronting the constable and protecting Flora (Chapter 11). This quiet act of defiance, inspired by her father's teachings and her compassion for Flora, highlights the unexpected strength found in seemingly delicate characters and foreshadows her later influence on March's healing.

Who are the most significant supporting characters?

- Ptolemy, the elderly manservant: Ptolemy's quiet dignity and eventual brutal murder (Chapter 12) serve as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of even the most seemingly protected enslaved individuals. His death, directly caused by March's inaction, becomes a profound source of March's self-loathing and a symbol of the war's indiscriminate cruelty.

- Jesse, the natural leader: Jesse's intelligence, mathematical aptitude, and leadership among the freed people (Chapter 8) highlight the immense potential suppressed by slavery. His eventual re-enslavement and March's failure to save him underscore the precariousness of freedom and the limits of March's individual efforts.

- Cephas White, the dying soldier-poet: Cephas White, the young amputee who writes a poignant poem about resignation ("I am ready not to do," Chapter 18), offers a profound philosophical counterpoint to March's relentless self-blame and desire for action. His quiet acceptance of fate challenges March's transcendentalist ideals and provides a moment of unexpected wisdom.

2. Psychological, Emotional, & Relational Analysis

What are some unspoken motivations of the characters?

- March's need for external validation: Beyond his genuine idealism, March is subtly driven by a deep-seated need for approval, particularly from Marmee and figures like John Brown. His decision to go to war, his financial ruin, and his self-censorship in letters are partly motivated by a desire to be seen as a hero or a man of unwavering principle, even at great personal cost.

- Marmee's suppressed rage and control: Marmee's "volatile temper" (Chapter 5) is not merely a character flaw but a manifestation of her suppressed anger and frustration at the constraints placed upon her as a woman in a patriarchal society. Her efforts at "self-mastery" (Chapter 7) are a constant battle against the emotional burdens she carries, particularly March's absence and their financial ruin.

- Grace's complex loyalty and self-preservation: Grace's decision to stay with Mr. Clement despite his past cruelty (Chapter 3) is driven by a complex mix of duty, compassion, and a profound, unspoken trauma related to her brother's death and her own violation. Her "modesty" (Chapter 3) in revealing her scars is a form of self-preservation, controlling the narrative of her suffering.

What psychological complexities do the characters exhibit?

- March's self-flagellation and survivor's guilt: March is consumed by an almost pathological self-blame, particularly after Ball's Bluff and the Oak Landing raid. His delirium reveals a mind tormented by perceived failures and cowardice, leading to a profound sense of unworthiness that prevents him from accepting comfort or returning home.

- Marmee's "morbid sympathy" and resilience: Marmee possesses an "uncommon ability to feel within herself what others must be feeling" (Chapter 7), which, while a source of her compassion, also makes her vulnerable to profound emotional distress. Her resilience lies in her ability to channel this intense empathy into practical action and to maintain the family's emotional core despite immense hardship.

- Canning's youthful arrogance masking vulnerability: Canning's initial "overzealous handshake" and "bluff manner" (Chapter 6) are a facade for his inexperience and deep financial anxiety. His physical decline and eventual confession of his fiancée's death (Chapter 13) reveal a man overwhelmed by circumstances, whose outward harshness is a coping mechanism for his own vulnerability and grief.

What are the major emotional turning points?

- The whipping of Grace: This event (Chapter 3) is March's first profound emotional turning point, shattering his youthful naiveté about slavery and imprinting him with a deep sense of guilt and complicity that fuels his later abolitionist fervor and self-reproach.

- Marmee's confrontation with Aunt March: Marmee's explosive reaction to Aunt March's offer to adopt Meg (Chapter 7) is a pivotal moment where her suppressed anger and the emotional toll of their poverty erupt. March's physical restraint of her marks a painful shift in their relationship, forcing them to confront the limits of their ideals and the raw emotions beneath their composure.

- March's cowardice during the Red Moon Raid: His paralysis by fear and subsequent hiding while Ptolemy and others are murdered (Chapter 12) is the nadir of March's moral journey. This act of self-preservation becomes the central source of his profound self-loathing and the "shame blazoned upon me like a brand" that he struggles to overcome.

How do relationship dynamics evolve?

- March and Marmee: From idealized union to fractured honesty: Their marriage begins as an intellectual and spiritual partnership, but March's self-censorship in his letters creates a chasm. Marmee's journey to Washington forces a painful reckoning, culminating in her confrontation with Grace and the slow, arduous process of rebuilding their relationship on a foundation of difficult truths and mutual forgiveness.

- March and Grace: A bond of shared trauma and moral reckoning: Their initial forbidden attraction evolves into a complex connection rooted in shared trauma and moral understanding. Grace becomes March's confessor and moral guide, her own profound suffering and resilience offering him a path to self-acceptance, even as their physical intimacy remains a source of Marmee's pain.

- March and Canning: From antagonism to reluctant respect: Their relationship begins with mutual disdain, March viewing Canning as a cruel pragmatist and Canning seeing March as a naive idealist. Through shared hardship and the revelation of their hidden vulnerabilities, their dynamic shifts to one of grudging respect and a shared, if often unspoken, understanding of the war's brutal realities.

4. Interpretation & Debate

Which parts of the story remain ambiguous or open-ended?

- The extent of March's healing: While March returns home and is embraced by his family, the novel leaves ambiguous the full extent of his psychological and spiritual recovery. He acknowledges the "ghosts of the dead" will be "ever at hand" (Chapter 19), suggesting that the trauma and guilt are not fully resolved but rather integrated into his new, diminished self.

- The future of the nation's ideals: The novel ends before the Civil War concludes, leaving the ultimate success of Reconstruction and the true realization of racial equality uncertain. March's journey reflects the nation's struggle, and the ending implies that the "river of fire" (Chapter 16) has irrevocably changed the landscape, with no easy path to a perfect future.

- The nature of March's "sin" with Grace: While Marmee confronts March about his "betrayal" and Grace reveals the depth of their connection, the precise nature and extent of their physical intimacy remain somewhat

Review Summary

March received mixed reviews, with many praising Brooks' writing and historical detail but criticizing her portrayal of characters from Little Women. Some found the novel deeply moving and thought-provoking, particularly in its exploration of Civil War themes and moral dilemmas. Others felt it betrayed the spirit of Alcott's original work, especially in its depiction of Marmee. The book's examination of idealism, slavery, and the human cost of war resonated with many readers, while some found the protagonist frustratingly naive.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.