Plot Summary

The Gesture That Lingers

The novel opens with the narrator observing an elderly woman at a Parisian pool. She waves to a lifeguard with a youthful, enchanting gesture, momentarily transcending her age. This gesture becomes the seed for the character of Agnes, the novel's central figure. The narrator muses on how gestures outlive individuals, suggesting that our actions, more than our identities, achieve a kind of immortality. This moment sets the tone for the book's exploration of the tension between the ephemeral and the eternal, the personal and the universal, and how a single, seemingly trivial act can echo through lives and stories.

Faces and the Self

Agnes, imagined from the poolside gesture, is introduced as a woman whose life is shaped by the accidental nature of her face and the roles she plays. The narrative explores how faces, like names, are arbitrary markers—serial numbers assigned by the "Creator's computer." Agnes's daily life is filled with routines, frustrations, and a longing for solitude, all while she is haunted by the sense that her self is not truly her own. The omnipresence of cameras and the gaze of others further erode the boundary between self and image, making privacy and authenticity nearly impossible. The chapter questions whether anyone can truly possess a unique self, or if we are all just bearers of recycled gestures and faces.

Sisters in Shadow

Agnes's relationship with her younger sister, Laura, is defined by imitation, competition, and unspoken resentment. Laura idolizes Agnes but also feels perpetually overshadowed and unlucky. Their lives diverge—Agnes chooses stability and marriage, Laura pursues artistic ambition and romantic adventure, yet both are dissatisfied. The sisters' bond is tested by family tragedies, inheritance secrets, and the struggle to define themselves outside of each other's influence. Their dynamic is a microcosm of the novel's larger themes: the search for meaning, the pain of comparison, and the impossibility of escaping the roles assigned by family and fate.

The Invention of Agnes

Agnes is not just a person but a literary creation, a vessel for the narrator's nostalgia and philosophical inquiry. Her existence blurs the line between fiction and reality, as the narrator openly discusses her artificial origins. Agnes's life is a series of gestures, routines, and memories—her father's death, her longing for solitude, her ambivalence toward her husband and daughter. The chapter delves into the idea that characters (and people) are less unique than the gestures they perform, and that our deepest yearnings are often for something outside of time, something immortal. Agnes's story becomes a meditation on the limits of individuality and the longing for transcendence.

The Tyranny of Images

The novel shifts to a critique of contemporary society, where images, not ideas, dominate. The rise of journalism, advertising, and public opinion polls has created a world where reality is mediated by imagology—the science of images. Politicians, journalists, and even ordinary people are trapped in a cycle of self-presentation and surveillance. The omnipresence of cameras and the demand for transparency erode privacy and authenticity. Agnes and her family are caught in this web, their lives shaped by how they are seen rather than who they are. The chapter explores the anxiety and alienation that result from living in a world where image is everything and substance is nothing.

Love, Marriage, and Escape

Agnes's marriage to Paul is marked by routine, affection, and a growing sense of estrangement. Their love is sustained more by will than passion, and both are haunted by the illusion of togetherness. Agnes dreams of escaping to Switzerland, seeking solitude and freedom from the gaze of others. Yet even in her fantasies, she cannot fully sever ties with her family. The chapter examines the paradox of intimacy: the desire to be known and the simultaneous need for privacy. It also explores the ways in which love can become a form of self-deception, a story we tell ourselves to give life meaning.

The Pursuit of Immortality

The narrative expands to consider the lives of historical figures—Goethe, Bettina von Arnim, Hemingway—and their quests for immortality. Through a blend of fiction and essay, the novel explores how the desire to be remembered shapes lives and legacies. Immortality is depicted as both a blessing and a curse, subjecting the famous to endless scrutiny and misinterpretation. The stories of Goethe and Bettina illustrate the futility of trying to control one's image after death, as well as the ways in which love, art, and ambition are all entangled in the longing to leave a mark on the world.

Goethe, Bettina, and Fame

The relationship between Goethe and Bettina becomes a case study in the complexities of fame, love, and historical memory. Bettina's obsessive love for Goethe is less about the man himself than about her own longing for significance. Their correspondence, real and imagined, becomes a battleground for competing narratives and interpretations. The chapter explores how stories are rewritten, how reputations are made and unmade, and how even the greatest lives are ultimately reduced to anecdotes, images, and misunderstandings. Immortality, the novel suggests, is not a reward but a perpetual trial in the court of public opinion.

The Age of Imagology

The novel returns to the present, analyzing how imagology has supplanted ideology as the organizing principle of society. Advertising, media, and public relations shape not only politics and culture but also personal identity. The distinction between reality and appearance collapses, and people become obsessed with their own images, seeking validation through visibility rather than substance. The chapter critiques the emptiness of modern fame, the commodification of selfhood, and the loss of genuine individuality. It also highlights the ways in which resistance to this system is co-opted and neutralized, leaving little room for authentic rebellion.

The Battle for Identity

Agnes, Laura, Paul, and their circle struggle to assert their identities in a world that constantly undermines them. Careers, relationships, and even acts of rebellion are filtered through the lens of public perception. The characters grapple with humiliation, envy, and the fear of being reduced to caricatures. The novel explores the psychological toll of living under constant observation and judgment, as well as the ways in which people internalize the expectations of others. The battle for identity becomes a performance, a negotiation between self and image, authenticity and artifice.

The Weight of the Body

The body, especially the female body, is a recurring source of anxiety, shame, and desire. Agnes and Laura experience their bodies as sites of vulnerability and power, subject to aging, illness, and the gaze of others. The novel examines the ways in which physicality shapes identity, relationships, and self-perception. Sexuality is depicted as both a means of connection and a source of alienation, with characters seeking redemption, affirmation, or oblivion through erotic encounters. The body becomes a metaphor for the self: mutable, fragile, and ultimately mortal.

The End of Love

As relationships unravel—Agnes's marriage, Laura's affair, the sisters' bond—the novel confronts the inevitability of loss and the inadequacy of love to overcome it. Death, separation, and misunderstanding expose the limits of intimacy and the persistence of solitude. The characters are left to grapple with regret, nostalgia, and the realization that even the deepest connections are provisional and incomplete. The end of love is not just a personal tragedy but a reflection of the broader human condition: the impossibility of fully knowing or possessing another person.

The Dial of Life

The metaphor of the dial—a clock, a horoscope, a cycle—structures the novel's meditation on time, fate, and repetition. Lives are depicted as variations on a theme, with patterns repeating across generations and relationships. Attempts to start anew or escape the past are shown to be illusory; the same issues, desires, and failures recur in different forms. The chapter weaves together stories of love, art, and memory, suggesting that meaning is found not in novelty but in the recognition of familiar motifs. The dial becomes a symbol of both limitation and continuity.

The Power of Chance

Chance events—missed connections, accidents, random encounters—play a decisive role in the characters' lives. The novel challenges the idea of a coherent, causally ordered narrative, emphasizing instead the unpredictability and contingency of existence. Coincidences are both meaningless and fateful, capable of transforming episodes into stories and shaping the course of lives. The chapter reflects on the limits of reason and the role of metaphor in making sense of experience, ultimately embracing the mystery and ambiguity of chance.

The Celebration and the End

The novel concludes with a scene of reunion and celebration at the health club, where the characters' stories intersect one last time. Agnes is gone, but her presence lingers in memory and gesture. Laura's wave—a reprise of the opening gesture—becomes a symbol of hope, continuity, and the possibility of transcendence. The characters are left to contemplate the meaning of their lives, the inevitability of loss, and the enduring power of small, beautiful acts. The final message is both melancholic and uplifting: immortality is not found in fame or achievement, but in the fleeting moments and gestures that connect us to others and to the world.

Characters

Agnes

Agnes is the novel's central figure, both a character and a literary invention. She is introspective, sensitive, and quietly dissatisfied with her life as a wife and mother. Haunted by the sense that her self is accidental and her gestures borrowed, Agnes longs for solitude and authenticity. Her relationships—with her husband Paul, her daughter Brigitte, and her sister Laura—are marked by ambivalence and yearning. Agnes's psychological depth lies in her acute awareness of the gap between appearance and reality, self and image. Her development is a gradual movement toward self-assertion, culminating in her decision to leave for Switzerland, seeking a kind of secular cloister. Her death is both a personal tragedy and a meditation on the limits of individuality and the persistence of memory.

Laura

Laura is Agnes's younger sister, defined by imitation, rivalry, and a sense of being perpetually unlucky. She is emotional, impulsive, and prone to melodrama, using her suffering as both a weapon and a badge of identity. Laura's relationships—with men, with Agnes, with her own body—are intense and often self-destructive. She seeks validation through love, sex, and acts of charity, yet remains fundamentally dissatisfied. Laura's psychological complexity lies in her oscillation between vulnerability and aggression, dependence and rebellion. Her development is marked by cycles of hope and despair, culminating in a near-suicidal crisis and a fraught reconciliation with Agnes.

Paul

Paul is Agnes's husband, a lawyer and commentator who prides himself on his wit, intelligence, and adaptability. He is both a product and a critic of modernity, embracing change while mourning the loss of tradition. Paul's relationships—with Agnes, Laura, his daughter Brigitte, and his colleagues—are shaped by his need for approval and his fear of obsolescence. He is psychologically torn between the desire for relevance and the anxiety of being reduced to an image. Paul's development is a journey from confidence to vulnerability, as he confronts professional setbacks, family conflicts, and the limits of his own adaptability.

Brigitte

Brigitte is Agnes and Paul's daughter, embodying the values and attitudes of a new generation. She is pragmatic, self-assured, and largely indifferent to the ideals and anxieties of her parents. Brigitte's relationship with her family is affectionate but detached; she is more interested in the present than the past, in image than substance. Psychologically, she represents the triumph of imagology over ideology, the replacement of depth with surface. Her development is less a personal journey than a reflection of broader cultural shifts.

Bernard Bertrand

Bernard is a radio commentator whose life is upended when he is publicly declared a "complete ass." He is ambitious, sensitive to criticism, and ultimately undone by the power of image and reputation. Bernard's relationships—with Laura, his father, and his colleagues—are marked by insecurity and a desperate need for validation. Psychologically, he is emblematic of the modern individual trapped in the web of public perception, unable to control or escape his own image. His development is a cautionary tale about the dangers of fame and the fragility of identity.

Professor Avenarius

Avenarius is a philosopher, provocateur, and friend to the narrator. He is skeptical, playful, and deeply alienated from the world he inhabits. Avenarius's relationships are marked by irony and detachment; he delights in subverting expectations and exposing the absurdities of modern life. Psychologically, he is both a critic and a participant in the games of image and identity, using humor and mischief as defenses against meaninglessness. His development is a movement toward acceptance of the world as a game, finding solace in play rather than purpose.

Goethe

Goethe appears both as a historical figure and a character in the novel's philosophical dialogues. He is reflective, proud, and increasingly weary of the demands of fame and legacy. Goethe's relationships—with Bettina, Christiane, and other immortals—are shaped by the tension between public image and private self. Psychologically, he embodies the paradox of immortality: the desire to be remembered and the horror of being endlessly scrutinized and misunderstood. His development is a gradual acceptance of mortality and the futility of controlling one's image.

Bettina von Arnim

Bettina is portrayed as a passionate, ambitious woman whose love for Goethe is less about the man himself than about her own longing for immortality. She is manipulative, theatrical, and driven by a need to be part of history. Bettina's relationships—with Goethe, her family, and other famous men—are marked by intensity and self-dramatization. Psychologically, she represents the dangers of conflating love with ambition, and the ways in which the pursuit of significance can become self-destructive. Her development is a relentless quest for recognition, ultimately achieving a kind of immortality through myth and legend.

Rubens

Rubens is a secondary protagonist whose life is traced through his relationships with women, his failed artistic ambitions, and his reflections on memory and desire. He is introspective, nostalgic, and increasingly obsessed with the past. Rubens's relationships are episodic, marked by longing and disappointment. Psychologically, he embodies the tension between experience and memory, the desire for meaning and the inevitability of loss. His development is a movement from hope to resignation, as he comes to terms with the limits of memory and the impossibility of recapturing the past.

The Narrator

The narrator is both a character and a meta-narrative presence, shaping the story and reflecting on its meaning. He is analytical, self-aware, and deeply engaged with the themes of identity, immortality, and the nature of fiction. His relationships—with his characters, with Avenarius, with the reader—are marked by irony and intimacy. Psychologically, he is both creator and creation, struggling with the boundaries between reality and imagination. His development is a journey toward acceptance of ambiguity, chance, and the limits of storytelling.

Plot Devices

Metafiction and Narrative Play

Kundera employs a self-referential narrative, frequently breaking the fourth wall to discuss the process of writing, the artificiality of characters, and the construction of meaning. The narrator openly invents and revises characters, blurring the line between author and creation. This device allows for philosophical digressions, commentary on the nature of fiction, and a constant questioning of reality versus imagination. The narrative structure is non-linear, episodic, and recursive, mirroring the themes of repetition and variation.

Gestures as Symbols of Immortality

The motif of the gesture—especially the wave—serves as a symbol of the enduring power of small, beautiful acts. Gestures outlive individuals, becoming part of a collective repertoire that transcends personal identity. This device underscores the novel's exploration of immortality, suggesting that what persists is not the self but the actions and images we leave behind. Gestures become a form of communication across generations, linking characters and stories.

Imagology and the Tyranny of Image

The concept of imagology—the science of images—serves as both a plot device and a thematic framework. Characters are obsessed with their public images, and their lives are shaped by the demands of visibility, surveillance, and self-presentation. The novel critiques the replacement of ideology with image, the commodification of identity, and the loss of authenticity in a world ruled by appearances. This device is reinforced by the omnipresence of cameras, mirrors, and public opinion polls.

Interwoven Historical and Fictional Narratives

The novel weaves together the stories of contemporary characters with those of historical figures like Goethe and Bettina. These parallel narratives serve to illustrate the universality of the search for immortality, the persistence of human folly, and the cyclical nature of history. The interplay between fiction and history allows for a rich exploration of memory, myth, and the construction of legacy.

The Dial and the Theme of Repetition

The metaphor of the dial—a clock, a horoscope, a cycle—structures the novel's meditation on time, fate, and recurrence. Characters' lives are depicted as variations on a theme, with patterns repeating across generations and relationships. This device challenges the idea of linear progress, emphasizing instead the inevitability of repetition and the limits of change.

Coincidence and the Limits of Reason

The novel frequently invokes coincidence, accident, and chance as forces that shape destinies and undermine the illusion of control. Characters' lives are altered by random events, missed connections, and unpredictable encounters. This device serves to question the adequacy of reason and causality in making sense of experience, highlighting the role of metaphor, ambiguity, and mystery.

Analysis

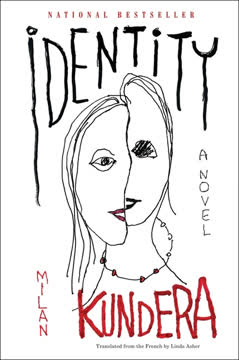

Immortality is Milan Kundera's most ambitious meditation on the nature of self, love, memory, and the longing for significance in a world dominated by images and chance. Through a blend of narrative, essay, and philosophical reflection, the novel interrogates the very possibility of individuality and authenticity in an age where gestures, faces, and stories are endlessly recycled and commodified. Kundera suggests that true immortality is not found in fame, achievement, or even love, but in the fleeting, beautiful moments and gestures that connect us to others and to the world. The novel is deeply skeptical of the promises of modernity—progress, transparency, self-invention—arguing instead for the acceptance of ambiguity, the inevitability of loss, and the enduring power of small acts. In the end, Immortality is both a lament for what has been lost and a celebration of what remains: the capacity for wonder, the persistence of memory, and the hope that even in a world of images, something real can endure.

Last updated:

FAQ

```markdown

0. Synopsis & Basic Details

What is Immortality about?

- A Philosophical Tapestry: Milan Kundera's Immortality weaves together the fictional lives of Agnes and Laura, two sisters in contemporary Paris, with philosophical essays and historical narratives featuring figures like Goethe and Bettina von Arnim. The novel explores the human longing for lasting significance, examining how individuals strive for "immortality" through fame, love, or memory in a world increasingly dominated by fleeting images and superficiality.

- The Birth of a Character: The story is sparked by the narrator's observation of an elderly woman's youthful gesture, which inspires the creation of Agnes. Her inner world, marked by a profound desire for solitude and authenticity, contrasts sharply with her sister Laura's dramatic pursuit of attention and love, setting up a central dynamic of the novel.

- Critique of Modernity: Beyond personal stories, the book offers a sweeping critique of modern European society, particularly the rise of "imagology"—the pervasive influence of media, advertising, and public opinion in shaping identity and reality. It questions the nature of the self, the meaning of love, and the possibility of genuine connection in an age where everything is mediated by image.

Why should I read Immortality?

- Deep Existential Inquiry: Immortality offers a profound exploration of what it means to be human, grappling with universal questions of identity, memory, and the desire to leave a lasting mark. Readers seeking intellectual stimulation and a novel that challenges conventional notions of self and society will find it deeply rewarding.

- Unique Narrative Structure: Kundera masterfully blends fiction, essay, and meta-commentary, creating a multi-layered reading experience that is both intellectually rigorous and emotionally resonant. The novel's unconventional form allows for rich philosophical digressions without sacrificing compelling character development.

- Timeless Relevance: Despite being written in 1990, the book's critique of image-driven culture, the erosion of privacy, and the pursuit of superficial fame feels remarkably prescient. It offers a powerful lens through which to understand contemporary anxieties about social media, celebrity culture, and the performance of self.

What is the background of Immortality?

- Post-Communist European Context: Written shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Immortality reflects Kundera's ongoing engagement with European history and culture, particularly the shift from ideological struggles to a new era dominated by media and consumerism. The novel implicitly contrasts the grand narratives of the past (e.g., Goethe's era, communist ideals) with the fragmented, image-saturated present.

- Kundera's Philosophical Concerns: The book continues Kundera's signature themes, such as the "unbearable lightness of being," the nature of kitsch, the role of chance, and the tension between public and private life. It builds upon his earlier works by introducing "imagology" as a key concept for understanding modern society's obsession with appearances.

- Autobiographical Echoes: While fictional, the narrator's voice often mirrors Kundera's own, particularly in his reflections on writing, the creation of characters, and his observations of Parisian life. The inclusion of a character named "Kundera" within the narrative further blurs the lines between author and creation, adding a meta-fictional layer.

What are the most memorable quotes in Immortality?

- "A gesture is more individual than an individual.": This aphorism, introduced early in the novel (Part One, Chapter 1), encapsulates Kundera's radical idea that our actions and expressions possess a life and meaning independent of the people who perform them. It challenges the notion of unique personal identity, suggesting that we are merely "bearers and incarnations" of universal gestures, a core Immortality theme.

- "Man doesn't know how to be mortal. And when he dies, he doesn't even know how to be dead.": Spoken by Goethe in his dialogue with Hemingway (Part Four, Chapter 16), this quote profoundly captures humanity's struggle with its own finitude. It highlights the inherent paradox of seeking immortality while being fundamentally incapable of accepting death, revealing a central Immortality meaning.

- "What is unbearable in life is not being but being one's self.": Agnes's profound realization (Part Five, Chapter 16) articulates her deep yearning to escape the burden of individual identity. This quote distills her quest for a "primordial being" beyond the confines of the self, offering a key insight into Agnes's motivations and the novel's exploration of existential freedom.

What writing style, narrative choices, and literary techniques does Milan Kundera use?

- Metafictional Interventions: Kundera frequently breaks the fourth wall, with the narrator directly addressing the reader, discussing the creation of characters (like Agnes), and reflecting on the novel's own construction. This technique, central to Immortality's narrative choices, blurs the lines between author, character, and reader, inviting active participation in the philosophical inquiry.

- Essayistic Digressions: The narrative is interspersed with philosophical essays on themes such as gestures, immortality, imagology, and the nature of love. These sections, often presented as the narrator's personal reflections or dialogues with Professor Avenarius, provide a theoretical framework for the fictional events, enriching the Immortality analysis with intellectual depth.

- Juxtaposition and Parallelism: Kundera employs a contrapuntal structure, weaving together seemingly disparate storylines—contemporary Parisian life, historical accounts of Goethe and Bettina, and the narrator's own observations. This literary technique highlights recurring patterns and themes across different eras and individuals, emphasizing the cyclical nature of human experience and the "dial of life."

1. Hidden Details & Subtle Connections

What are some minor details that add significant meaning?

- The Elevator's Moods: Agnes's capricious elevator (Part One, Chapter 2) that "twitched like a person afflicted with Saint Vitus' dance" and "refused to open" is more than a mere inconvenience. It subtly symbolizes her feeling of being trapped and controlled by external forces, mirroring her struggle for autonomy and her desire to escape the predetermined "program" of her life. This seemingly trivial detail foreshadows her later longing for freedom and solitude.

- Paul's Mother's Likeness: The narrator notes that Paul "looked incorrigibly like his mother" and that Agnes found this likeness "painfully unpleasant," even imagining "an old woman... distorted with lust" during lovemaking (Part One, Chapter 7). This detail subtly reveals Agnes's deep-seated discomfort with the physical aspects of aging and the loss of individual distinctiveness, linking her personal anxieties to the novel's broader themes of faces, bodies, and the erosion of the unique self.

- The "Crazy Woman with the Forget-Me-Not": Agnes's fantasy of walking through Paris holding a single forget-me-not to shield herself from ugliness (Part One, Chapter 5) is a poignant, almost desperate act of aesthetic resistance. This detail symbolizes her profound alienation from modern society's visual and auditory assault, highlighting her yearning for a singular, pure beauty in a world overwhelmed by noise and vulgarity, a key aspect of Agnes's psychological complexities.

What are some subtle foreshadowing and callbacks?

- Goethe's "Annoying Gadfly" and Paul's "Gravediggers": Goethe's eventual outburst against Bettina as an "annoying gadfly" (Part Two, Chapter 10) is subtly echoed when the Bear calls Paul the "brilliant ally of his own gravediggers" (Part Three, Chapter 10). This parallelism foreshadows Paul's professional downfall and his unwitting complicity in the very forces (imagology, superficiality) that undermine his intellectual values, linking his fate to the historical figures' struggles with immortality and fame.

- The "Creator's Computer" and Predestination: Agnes's father's belief in the "Creator's computer" (Part One, Chapter 3) that sets "limits of possibilities" but leaves "power of decision... to chance" subtly foreshadows the novel's later exploration of fate and free will. This concept recurs in the "dial of life" metaphor, suggesting that while individual choices exist, they operate within a predetermined "theme," a crucial element in Immortality's themes.

- Laura's "Vomiting" Metaphor: Laura's frequent declaration, "The moment he left I had to throw up," to express desperation (Part Three, Chapter 4) is a callback to Gala Dali's literal act of vomiting her beloved pet rabbit. This connection subtly highlights Laura's intense, visceral identification with her body and emotions, contrasting with Agnes's more detached, intellectual approach, and foreshadowing Laura's later dramatic, body-centric actions, revealing Laura's motivations.

What are some unexpected character connections?

- Paul's Lawyer and Avenarius's Tire Slashing: The lawyer who offers Avenarius his card after the "rape" accusation is later seen kneeling by a car wheel (Part Five, Chapter 18), implying he is also slashing tires. This unexpected connection reveals a hidden network of individuals engaged in seemingly irrational acts of rebellion against modern society, suggesting a shared, albeit eccentric, resistance to "Diabolum" that transcends social roles. It adds a layer of dark humor and solidarity among the novel's outsiders.

- Laura's "Something" Gesture and Bettina's Longing: Laura's gesture of placing her hands on her chest and flinging them forward when speaking of doing "something" (Part Three, Chapter 17) is explicitly identified as identical to Bettina's "gesture of longing for immortality" (Part Three, Chapter 17). This direct link, though separated by centuries, reveals a shared, primal human drive for self-transcendence and recognition, connecting Laura's personal drama to the grand historical quest for immortality explained.

- Rubens's "Lute Player" and Goethe's "Bed-Treasure": Rubens's idealized "lute player" (Part Six, Chapter 9), whom he meets after years, is a woman he had once touched intimately. This echoes Goethe's "bed-treasure" Christiane, who was excluded from his "love" narratives because she was his sexual partner. This connection subtly critiques the historical separation of physical intimacy from idealized love, suggesting that Rubens, like Goethe, struggles with the dichotomy between erotic reality and romantic illusion, a key aspect of Rubens's psychological complexities.

Who are the most significant supporting characters?

- Professor Avenarius: More than just the narrator's friend, Avenarius embodies the novel's spirit of playful, melancholic rebellion. His "fight against Diabolum" through absurd acts like tire-slashing and his philosophical dialogues with the narrator provide a crucial meta-commentary on the themes of meaninglessness, freedom, and the limits of organized resistance. He is a living embodiment of the novel's intellectual and ironic core, offering a unique perspective on Immortality's themes.

- The Narrator (Milan Kundera): As the author-character, the narrator is arguably the most significant "supporting" character, as he orchestrates the entire narrative, openly discussing his creative process and philosophical intentions. His presence constantly reminds the reader of the constructed nature of reality and fiction, making him a central figure in the novel's metafictional exploration of storytelling and identity.

- The "Girl on the Highway": Though unnamed and appearing only in a news report and the narrator's imagination, this suicidal girl (Part Three, Chapter 1) becomes a powerful symbol of extreme alienation and the destructive potential of a "reason deprived of reason." Her story, analyzed by the narrator and Avenarius, serves as a stark counterpoint to the characters' quests for immortality, highlighting the profound despair that can arise from a lost connection to the world, offering a deep analysis of Immortality's symbolism.

2. Psychological, Emotional, & Relational Analysis

What are some unspoken motivations of the characters?

- Agnes's Escape from the "Gaze": Agnes's deep longing for solitude and her decision to move to Switzerland are driven by an unspoken desire to escape the constant "looks" of others, which she perceives as "weights that pressed her down" and "needles that etched the wrinkles in her face" (Part One, Chapter 6). Her motivation is not just for peace, but for an erasure of the external self, a retreat from the tyranny of image that she feels is consuming her, revealing Agnes's motivations.

- Paul's Pursuit of Youthful Validation: Paul's enthusiastic embrace of "absolute modernity" and his reliance on Brigitte's opinions (Part Three, Chapter 12) are subtly motivated by a fear of obsolescence and a desperate need to remain relevant and "young." His intellectual arguments for frivolity and the end of high culture serve as a defense mechanism against his own aging and the perceived loss of his "image" in the eyes of the world, a key aspect of Paul's psychological complexities.

- Laura's Weaponization of Suffering: Laura's melodramatic pronouncements of suffering, her dark glasses, and her suicidal threats are not merely expressions of pain but a calculated, albeit unconscious, strategy to gain attention and exert control over others, particularly Bernard and Agnes. Her "hypertrophy of the soul" (Part Four, Chapter 11) is a means of demanding emotional engagement and proving her own significance, offering insight into Laura's motivations and her complex emotional landscape.

What psychological complexities do the characters exhibit?

- Agnes's Existential Shame: Agnes experiences a profound "basic shame" (Part Five, Chapter 12) not tied to personal mistakes, but to the "ignominy... that we must be what we are without any choice in the matter." This shame, linked to her physical body and the accidental nature of her face, reveals a deep existential discomfort with her own given existence, driving her quest for a self beyond physical and social constraints, a core aspect of Agnes's psychological complexities.

- Goethe's Vanity and Self-Deception: Despite his intellectual prowess, Goethe is shown to be susceptible to vanity, particularly regarding his image and legacy. His "tear" over Bettina's monument sketch is later recognized as a "banal truth of his own vanity" (Part Four, Chapter 12), highlighting the human tendency to interpret events through a self-serving lens, even for historical giants. This reveals the psychological complexities of Goethe and the universal struggle with self-perception.

- Bernard's Fragile Identity and Public Humiliation: Bernard's reaction to being declared a "complete ass" (Part Three, Chapter 8) is a deep psychological wound, not just a professional setback. His subsequent withdrawal and shame reveal a fragile identity heavily dependent on external validation and public opinion. His inability to separate his "self" from his "image" underscores the novel's critique of imagology and the vulnerability of the modern individual, offering a detailed Bernard Bertrand analysis.

What are the major emotional turning points?

- Agnes's Father's Death and Inheritance: Her father's death (Part One, Chapter 4) is a pivotal emotional turning point for Agnes, not just due to grief, but because of the secret inheritance and his final message to "be free." This act of trust and rebellion from her taciturn father profoundly influences Agnes's subsequent longing for solitude and her eventual decision to leave Paul and Brigitte, shaping Agnes's emotional journey.

- Laura's Miscarriage and the Dark Glasses: Laura's miscarriage (Part Three, Chapter 1) is a devastating emotional blow that transforms her use of dark glasses from a fashion statement into a "badge of sorrow." This event marks a shift in her character, intensifying her self-dramatization and her use of suffering to elicit sympathy and attention, becoming a major emotional turning point in Laura's character development.

- Paul's Confrontation with the Bear and Brigitte's Influence: The cancellation of Paul's radio show and the Bear's accusation of being an "ally of his own gravediggers" (Part Three, Chapter 10) is a significant emotional turning point, forcing Paul to confront the fragility of his public image and his own intellectual compromises. His subsequent reliance on Brigitte's "clairvoyant" youth for validation further highlights his emotional vulnerability and the generational shift in values, revealing Paul's emotional turning points.

How do relationship dynamics evolve?

- Agnes and Laura: From Imitation to Antagonism: The sisters' relationship evolves from Laura's childhood admiration and imitation of Agnes to a deep-seated rivalry and open antagonism, particularly after Agnes's father's death and Laura's personal misfortunes. Their final, hateful argument (Part Three, Chapter 18) reveals the destructive power of unspoken resentments and competing needs for validation, illustrating the complex relationship dynamics between them.

- Paul and Agnes: The Illusion of Love: Their marriage, initially sustained by "the illusion of love" and "will to love" (Part One, Chapter 9), gradually reveals a growing emotional distance. Agnes's dreams of leaving and Paul's increasing reliance on Brigitte highlight their unspoken dissatisfactions. Their final moments together, marked by Agnes's desire for Paul not to see her dying, underscore the ultimate solitude within even the most intimate relationships, providing a poignant analysis of Paul and Agnes's relationship.

- Laura and Bernard: The Perils of Public Love: Their affair, initially a thrilling escape for both, deteriorates under the pressure of Bernard's public humiliation and Laura's escalating demands for commitment. Laura's "fighting" through sex and her public complaints transform their private intimacy into a battleground, demonstrating how external pressures and internal insecurities can corrupt even passionate connections, a key aspect of Laura's relationship dynamics.

4. Interpretation & Debate

Which parts of the story remain ambiguous or open-ended?

- The Nature of the Narrator's Reality: The narrator's direct involvement in the story, his creation of characters, and his dialogues with Professor Avenarius blur the lines between fiction and reality. It remains ambiguous whether the "narrator" is a character within the novel's world, a stand-in for Kundera himself, or a purely metafictional construct, leaving readers to debate the Immortality meaning of his presence and the extent of his control over the narrative.

- Agnes's True Motivations for Leaving: While Agnes expresses a desire for solitude and escape, the precise depth and sincerity of her decision to move to Switzerland remain somewhat ambiguous. Her internal monologue oscillates between firm resolve and practical anxieties, leaving open the question of whether her "yes" to the job offer was a genuine act of liberation or another form of self-deception, inviting interpretive debate on Agnes's motivations.

- The "Girl on the Highway" Identity and Fate: The unnamed girl who attempts suicide on the highway is never fully identified or given a definitive backstory. Her "Grund" (reason/basis) is left to the narrator's metaphorical interpretation, and her ultimate fate after running away is unknown. This ambiguity emphasizes the novel's theme of chance and the unknowability of individual suffering, prompting readers to ponder the symbolism of the girl on the highway and the limits of narrative explanation.

What are some debatable, controversial scenes or moments in Immortality?

- Goethe's "Annoying Gadfly" Letter: Goethe's harsh letter calling Bettina an "annoying gadfly" (Part Two, Chapter 10) is a controversial moment, especially given his earlier attempts to maintain a "kind control." This scene sparks debate about the true nature of his feelings for Bettina, whether it was a moment of genuine exasperation or a calculated move to protect his image, and how it impacts his historical legacy, fueling Goethe's character analysis.

- Paul's Encouragement of Laura's Trip to Martinique: Paul's decision to tell Laura to "do exactly what you feel like doing" regarding her trip to Martinique (Part Three, Chapter 16), despite his internal belief that it was "totally nonsensical," is highly debatable. This moment raises questions about his responsibility, his fear of "forbidding," and whether his actions were driven by a misguided principle or a subtle desire for dramatic outcome, leading to Paul's motivations being questioned.

- Rubens's "Crucifixion" Vision of the Lute Player: Rubens's vision of the lute player crucified, covering her bare breasts while being gazed upon by a crowd (Part Six, Chapter 22), is a controversial and disturbing image. This scene can be debated for its eroticization of suffering, its commentary on female vulnerability to the male gaze, and its symbolic connection to the historical objectification of women, offering a rich ground for Immortality symbolism analysis.

Immortality Ending Explained: How It Ends & What It Means

- The Enduring Gesture: The novel concludes with Laura, Paul's new wife, performing the same graceful wave that initially inspired the creation of Agnes, directed at Avenarius and the narrator. This gesture, described as a "golden ball" shining above the doorway (Part Seven, Chapter 4), symbolizes the enduring power of human gestures and the cyclical nature of life, even after Agnes's death. It suggests that while individuals perish, certain expressions and patterns of human experience achieve a kind of Immortality explained through repetition.

- Paul's Acceptance of the "Eternal Feminine": Paul, initially a critic of "high culture" and a proponent of "frivolity," embraces the idea of "Das Ewigweibliche zieht uns hinan! The eternal feminine draws us on!" (Part Seven, Chapter 4). This signifies his ultimate surrender to the irrational, the emotional, and the life-affirming forces embodied by women, particularly Laura. His clumsy imitation of Laura's wave, though comical, represents his acceptance of a future guided by intuition and hope, rather than reason, a key aspect of Paul's character development.

- The Narrator's Metaphorical Understanding: The narrator finally finds his "right metaphor" for Avenarius: "a melancholy child who has no little brother" (Part Seven, Chapter 5), signifying his understanding of Avenarius's playful rebellion as a solitary game against a world he cannot take seriously. The ending reinforces the novel's metafict

Review Summary

Immortality is a philosophical novel by Milan Kundera that explores themes of identity, love, and the human desire for lasting significance. Readers praise Kundera's unique narrative style, blending multiple storylines and philosophical musings. The book is lauded for its profound insights into the human condition, witty observations, and ability to challenge conventional thinking. While some find the non-linear structure and digressions challenging, many consider it a masterpiece that rewards careful reading and reflection.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.