Key Takeaways

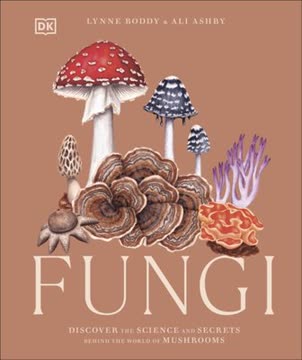

1. Fungi: An Ancient, Distinct Kingdom Essential for Life

Because one thing is certain: we could not survive on Earth without fungi.

A separate kingdom. Fungi, once grouped with plants, are now recognized as a distinct kingdom of life, more closely related to animals than to plants. They first appeared on Earth around 1 billion years ago, evolving from simple, single-celled organisms into the diverse forms we see today, from microscopic yeasts to vast underground networks and visible mushrooms. This ancient lineage highlights their fundamental role in shaping our planet's ecosystems.

Ubiquitous presence. Scientists estimate there are 5 million species of fungi, present in nearly every habitat on Earth, from deep-sea caves to human bodies. They exist as individual cells, fine filaments called hyphae, or complex networks known as mycelia, which can spread over enormous distances. This widespread distribution underscores their adaptability and critical involvement in global biological processes.

Life's foundation. Fungi are indispensable to life on Earth, acting as the planet's best recyclers by breaking down dead organic matter. Without them, essential nutrients would remain locked away, preventing the formation of fertile soil necessary for new plant life. Their ancient origins and pervasive influence confirm that fungi are not just an interesting biological curiosity, but a cornerstone of our world's survival.

2. The Hidden World: Mycelium, the True Body of Fungi

The main body of a tree is its roots, trunk, and branches. Likewise, the main structure of a filamentous fungus is its fine hyphae that form networks called mycelia, which are often hidden from view.

Mycelial networks. While mushrooms are the visible "fruits" of fungi, the true body is the mycelium—a vast, often hidden network of fine, thread-like hyphae. These microscopic filaments, up to 40 times thinner than a human hair, spread through soil, wood, or living organisms, forming intricate, long-lived structures. Mycelia are crucial for nutrient absorption and communication within the fungal organism.

Unassuming power. Mycelia can penetrate solid materials using both physical force and digestive enzymes, allowing them to bore into wood or even tarmac. Their immense surface area is perfectly adapted for external digestion and nutrient absorption, making them highly efficient foragers. Some individual mycelial networks are among the largest living organisms on the planet, spanning square kilometers and weighing hundreds of tons.

Life cycle foundation. A new mycelium develops from a single spore, germinating into hyphae that branch and spread. When conditions are right, and often after mating with a compatible partner, the mycelium gears up to produce fruit bodies. These structures then release millions of spores, ensuring the fungus's spread and continuation of its life cycle.

3. Fungi's Vital Role as Earth's Ultimate Recyclers

They are the Earth’s best recyclers: without them, the nutrients in dead trees and other organic matter would be locked up and there would be no fertile soil to grow new plant life.

External digestion. Fungi cannot make their own food like plants; instead, they digest food outside their bodies by secreting powerful enzymes. These enzymes break down complex organic matter into smaller molecules, which the hyphae then absorb. This unique feeding strategy allows fungi to process virtually any naturally produced compound.

Decomposers extraordinaire. Most fungi are saprotrophs, feeding on dead plant, animal, and microbial matter. They break down fallen leaves, dead wood, and animal remains, returning vital nutrients to the soil. This decomposition is essential for nutrient cycling, preventing the accumulation of organic waste and creating fertile ground for new life.

Diverse digestive capabilities. Across the fungal kingdom, there is an incredible array of digestive enzymes, enabling fungi to break down even the toughest materials like lignin in wood. This makes them indispensable in various ecosystems, from forests to gardens, where they continuously transform waste into usable resources, underpinning the health and productivity of the planet.

4. Nature's Networkers: Fungi's Indispensable Partnerships

The roots of 90 per cent of plants form mycorrhizal partnerships – probably the most frequent and vital close relationships between organisms from different kingdoms.

Ancient alliances. Fungi form crucial partnerships with plants and algae, dating back hundreds of millions of years. Mycorrhizal associations, where fungi connect with plant roots, were essential for plants to colonize land, providing water and nutrients in exchange for sugars from photosynthesis. These partnerships are still vital for almost every plant on Earth.

The "Wood Wide Web". Beneath forests, mycelial networks of mycorrhizal and wood-decay fungi connect trees and rotting vegetation. These "wood wide webs" facilitate the exchange of nutrients, sugars, water, and chemical messages between trees, even across different species. This interconnectedness is fundamental to forest health and resilience.

Lichens: symbiotic pioneers. Lichens are remarkable organisms formed by fungi partnering with green algae or cyanobacteria. The fungus provides protection from desiccation and UV radiation, while the photobiont produces carbohydrates. These resilient partnerships allow lichens to thrive in extreme environments, from polar regions to exposed rocks, acting as pioneers in harsh habitats.

5. Masters of Adaptation: Fungi Thrive in Every Niche

Wherever there is a source of food and moisture, you will find a fungus. Fungi are everywhere: from the Arctic to the tropics, in water and on land, in the air and within plants and animals, and even in space.

Ubiquitous habitats. Fungi demonstrate incredible adaptability, colonizing virtually every environment on Earth. They are found in diverse outdoor settings like soils, compost heaps, and log piles, and even in unexpected places such as deep-sea sediments, rocks, and caves. Their presence extends to aquatic environments, including freshwater and oceans, and even within the human body.

Extreme survival. Fungi have evolved specialized adaptations to survive harsh conditions. In polar regions like Antarctica and the Arctic, they produce antifreeze proteins and glycerol to prevent ice crystal formation, and their cell walls are adapted to resist brittleness in extreme cold. Some fungi thrive after fires, with spores stimulated to germinate by intense heat, demonstrating their resilience to environmental disturbances.

Sensory perception. Fungi possess a range of senses to navigate their environments, responding to light, touch, chemicals, and temperature. While they don't "see" or "hear" like animals, they use photoreceptors to grow towards light for spore dispersal and can sense surface changes to find entry points into host plants. This sophisticated sensory system enables their survival and propagation across diverse niches.

6. Fungi's Dark Side: Pathogens, Toxins, and Disease

Some fungi can cause disease and even death to plants and other organisms, yet most plants and also many animals would not survive without the beneficial partnerships they form with fungi.

Crop devastation. Fungi are responsible for over 70% of plant diseases, posing a significant threat to global food production. Rusts, mildews, and rots can lay waste to hundreds of millions of tons of crops annually, as seen with the devastating Panama disease threatening bananas. Humans inadvertently spread these fungal killers through international trade, altering landscapes and ecosystems.

Animal and human threats. Emerging fungal diseases are increasingly impacting animal populations, causing widespread concern. Chytridiomycosis is decimating amphibian populations worldwide, while bat white-nose syndrome threatens bat species in North America and Europe. In humans, opportunistic fungi like Candida and Cryptococcus can cause serious, even fatal, infections in immunocompromised individuals.

Toxic compounds. Many fungi produce toxins as defense mechanisms against competitors, which can be harmful or deadly to humans and animals. Mycotoxins, like aflatoxins, contaminate food and can cause liver disease and cancer. Poisonous mushrooms contain potent toxins like amatoxins, which are heat-stable and can cause cell damage, highlighting the critical need for accurate identification.

7. From Ancient Remedies to Modern Miracles: Fungi in Medicine

Ancient cultures have used fungi for healing for thousands of years. Today, fungi are behind many mainstream medicines – from penicillin and other common antibiotics to medicines that can help combat high cholesterol – and they are being studied as potential forms of treatment for some cancers and mental health conditions.

Traditional healing. For millennia, cultures worldwide have revered fungi for their medicinal properties. Chaga, Ganoderma lucidum (reishi/lingzhi), and shiitake mushrooms have been used in traditional Chinese and Japanese medicine to boost immunity, treat various ailments, and promote well-being. The birch polypore, found in Ötzi the Iceman's kit, was used as a styptic and for its anti-inflammatory properties.

Antibiotic revolution. The accidental discovery of penicillin from Penicillium rubens by Alexander Fleming in 1928 revolutionized medicine, providing cures for previously fatal bacterial infections. This "wonder drug" paved the way for a new era of antibiotics, saving countless lives, though its widespread use has also led to challenges with antibiotic resistance.

Modern therapeutic potential. Fungi continue to be a source of groundbreaking medicines. Cyclosporine, derived from Tolypocladium inflatum, is a vital immunosuppressant for organ transplant patients. Fungal endophytes produce paclitaxel (Taxol), a valuable cancer drug. Furthermore, compounds like psilocybin from liberty caps are being researched for their potential to treat mental health conditions like anxiety and depression.

8. Beyond Food: Fungi as Innovators in Sustainable Technology

Fungi are working behind the scenes in many everyday processes that we take for granted: fungi dye our clothes, clean our homes, and give us cheese, wine, and soy sauce. They might also be the key to a greener future.

Mycotechnology's rise. Fungi are increasingly recognized as a "supermaterial" for sustainable solutions. Mycelium, with its strength, water resistance, and fire-retardant properties, can be manipulated to grow into eco-friendly building blocks, packaging, and furniture. This offers biodegradable alternatives to conventional materials, supporting circular economies.

Enzymatic powerhouses. Fungi produce a vast array of enzymes that are harnessed for industrial applications, offering greener alternatives to chemical processes. These enzymes are used in:

- Food and dairy (e.g., citric acid, cheese ripening)

- Textiles (e.g., cellulases for stone-washed jeans)

- Detergents (e.g., amylases, lipases, proteases)

- Biofuel production

Environmental remediation. Fungi hold immense potential for "myco-remediation," breaking down various forms of waste. Species like Aspergillus tubingensis and Penicillium simplicissimum can degrade plastics, including polyurethane and polyethylene. Mycorrhizal fungi can also help clean up dangerous contaminants like uranium deposits, making them less active or localizing them within their hyphae, contributing to a greener planet.

9. Cultural Threads: Fungi Woven into Human History and Art

Mushrooms have featured in art, folklore, music, and rituals for as long as humans have walked this planet.

Myths and legends. The mysterious appearance of mushrooms has fueled centuries of folklore. Fairy rings were once believed to be sites of magic or dragon activity, while the iconic fly agaric is linked to the origins of Santa Claus in Siberian shamanic traditions. Ancient cultures revered fungi, associating them with fertility, immortality, and supernatural powers.

Artistic inspiration. Fungi have been widely represented in art, from prehistoric cave drawings and Neolithic stone carvings to Renaissance paintings and 20th-century stamps. Artists like Beatrix Potter meticulously documented fungi, while others, such as Giuseppe Arcimboldo, incorporated them into symbolic works. The lingzhi mushroom (Ganoderma lucidum) is a prominent symbol in East Asian art, representing good health and luck.

Beyond visual arts. Fungi's influence extends to music and literature. The unique patterns of spore release can be translated into delicate "mushroom music." Fungi-treated "myco-wood" has been used to craft violins with enhanced acoustic properties, rivaling Stradivarius instruments. Literature, from Beowulf to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, has drawn inspiration from fungi's bioluminescence, decay, and hallucinogenic effects.

10. The Unseen Majority: Vast Fungal Diversity Awaits Discovery

With a predicted 90 per cent of all fungi still to be discovered, we are only at the tip of the iceberg.

Known unknowns. While scientists have described over 120,000 species, estimates suggest the true number of fungi on Earth could be as high as 5 million, or even 12 million if "dark matter" fungi (identifiable only by DNA) are included. This vast, undiscovered diversity means we are only beginning to understand the full scope of the fungal kingdom. Advances in DNA technology are continually revealing new species in previously unexplored environments.

Ongoing exploration. Mycology, the study of fungi, continues to be a dynamic field of discovery. Every new habitat investigated, from deep-sea sediments to the human microbiome, yields novel fungal signatures. This ongoing exploration is crucial for understanding their ecological roles, potential benefits, and threats.

Future implications. The vast majority of fungi remain a mystery, yet they play critical roles in every ecosystem. Discovering and understanding these unknown species could unlock new solutions for medicine, sustainable materials, and environmental challenges. The more we learn about this hidden kingdom, the more we appreciate its profound and indispensable impact on our planet and our lives.

Last updated: