Key Takeaways

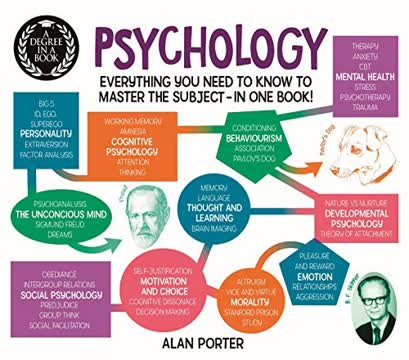

1. Psychology: A Systematic Quest to Understand Mind and Behavior

What brings together these different areas of psychology is that, despite differences in conceptual vocabulary and differences in research methods, all these different kinds of psychology approach their subject matter systematically and empirically.

A varied discipline. Psychology is a vast and diverse field, exploring everything from universal processes like learning and memory to individual differences in intelligence and personality. It systematically investigates human experience, moving beyond mere speculation to support theories with evidence. This empirical approach, pioneered by figures like Wilhelm Wundt, established psychology as a distinct science.

Foundational roots. The discipline emerged from a "long past" of philosophical inquiry into human nature, but its "short history" began in the late 19th century with the establishment of the first experimental psychology lab by Wilhelm Wundt in Leipzig in 1879. Wundt focused on conscious experience, using controlled introspection to study simple sensory processes, aiming for objectivity akin to chemistry or physics. However, this narrow scope soon fragmented the field.

Academic and professional growth. From its humble beginnings, psychology has grown exponentially, becoming a popular degree subject globally and attracting significant funding. This academic expansion has fueled a rise in professional psychologists who apply research to advise, treat, and counsel individuals in various settings, from medical to educational and corporate environments.

2. Learning: From Reflexes to Insightful Problem-Solving

Pavlov called this phenomenon psychic salivation because it was brought about by a mental connection rather than a physical connection and was intrigued by the way a reflex action could be triggered by something to which it had no natural connection and was clearly the result of previous experience, ordered through a process of association.

Behaviorism's rise. Early 20th-century psychology, frustrated by the subjectivity of introspection, saw the rise of Behaviorism, which sought to explain the mind through publicly observable and measurable behavior. Ivan Pavlov's work on "psychic salivation" in dogs demonstrated classical conditioning, where a neutral stimulus could trigger a reflex through association, laying the groundwork for this new approach.

Conditioning principles. John B. Watson, a key figure in Behaviorism, championed Pavlov's principles, famously demonstrating conditioned emotional responses in "Little Albert." B.F. Skinner later developed operant conditioning, showing how behavior is shaped by its consequences (reinforcement or punishment) through interaction with the environment, as seen in his "Skinner Box" experiments with rats and pigeons.

Beyond association. While behaviorism dominated for decades, explaining learning as a gradual, associative process, other perspectives emerged. Gestalt psychologists like Wolfgang Köhler, studying chimpanzees, argued that learning could also involve "insight"—a sudden reorganization of understanding—which couldn't be reduced to simple stimulus-response chains, highlighting the role of mental processes.

3. Cognition: The Mind as an Information Processor

All the activities I have described are the subject matter of cognitive psychology, which studies how information is encoded, stored, manipulated and transmitted in order to model and explain the functioning of the human mind.

A new paradigm. Cognitive psychology emerged in the 1960s, shifting focus from observable behavior to internal mental processes, often using the computer as a metaphor for the mind. This approach investigates how we perceive, remember, think, and solve problems, moving "inside the black box" that behaviorists avoided.

Memory's mechanisms. Early cognitive research, building on Hermann Ebbinghaus's systematic studies of memory using nonsense syllables and Frederic Bartlett's work on memory as a constructive process, began to model memory structures. George A. Miller's "Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two" highlighted the limited capacity of short-term memory, introducing concepts like "chunking" to explain how we manage information.

Models of mind. Atkinson and Shiffrin proposed the "modal model" of memory, distinguishing between sensory, short-term, and long-term stores, while Baddeley and Hitch refined this with the "working memory model," emphasizing active processing. Donald Broadbent's filter theory of attention illustrated how the mind selectively processes information, preventing overload and demonstrating the intricate architecture of human cognition.

4. Biological Psychology: Unraveling the Brain-Mind Connection

Cognitive neuroscientists believe that it is essential to understand the brain and nervous system and argue that a fully developed cognitive neuroscience will integrate research from experimental psychology with research on brain anatomy and the organisation of the nervous system to give us a complete picture of human psychology.

From pneuma to neurons. Historically, understanding the brain evolved from ancient Greek notions of "pneuma" flowing through "nerves" to the 17th-century realization that the brain's outer cortex, not its ventricles, was the seat of mental activity. Thomas Willis and Christopher Wren meticulously mapped brain anatomy, setting the stage for localizing mental functions.

Localization of function. The 19th century saw significant strides in linking specific brain areas to functions. Franz Gall's phrenology, though flawed in its skull-mapping, correctly emphasized brain localization. Later, clinicians like Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke identified specific brain regions responsible for speech production and comprehension, respectively, through post-mortem examinations of patients with aphasia.

Electrical brain. The discovery of "animal electricity" by Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta revealed the electrical nature of nerve impulses. Eduard Hitzig and Gustav Fritsch demonstrated the electrical excitability of the cerebral cortex, leading to the mapping of motor and sensory areas. Modern non-invasive techniques like EEG, fMRI, and TMS now allow real-time observation of the active brain, deepening our understanding of the mind-brain relationship.

5. Development: A Lifelong Journey Shaped by Interaction

Piaget called this undertaking genetic epistemology; ‘genetic’ because it is concerned with development and ‘epistemology’ because it is concerned with knowledge.

Early influences. The study of child development has roots in philosophical debates, with Jean-Jacques Rousseau advocating for active, experience-based learning. Charles Darwin's observations of his own children provided early systematic data, while James Mark Baldwin attempted to synthesize physical and mental development from an evolutionary perspective.

Piaget's stages. Jean Piaget's "genetic epistemology" mapped cognitive development through universal, invariant stages, driven by assimilation and accommodation. His experiments, like the "Three Mountain Problem," revealed qualitative shifts in children's thinking, such as overcoming egocentrism and understanding conservation, profoundly influencing education.

Social and emotional dimensions. Lev Vygotsky offered a social constructionist view, emphasizing that cognitive development is synonymous with socialization and that thought is internalized speech, with learning occurring within the "zone of proximal development." Beyond cognition, psychoanalytic theories (Freud's oral, anal, phallic stages) and attachment theory (John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth) highlighted the crucial role of early social and emotional experiences in shaping personality and relationships.

6. Social Psychology: The Profound Influence of Others

Wundt’s argument that social psychology was different from experimental psychology was never totally dismissed and to this day there are psychologists who have tried to keep alive the Völkerpsychologie tradition.

Beyond the individual. Social psychology explores how individuals' thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others. While Wundt's "Völkerpsychologie" emphasized collective phenomena, modern social psychology largely adopted experimental methods to study attitudes, group dynamics, and social influence.

Attitudes and influence. Early research focused on measuring and changing attitudes, though Richard LaPiere's work revealed a complex relationship between expressed attitudes and actual behavior. Leon Festinger's cognitive dissonance theory showed how people change their own attitudes to resolve internal inconsistencies. Studies like Stanley Milgram's obedience experiments and Philip Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment dramatically demonstrated the powerful impact of authority and roles on individual actions.

Group dynamics. Social psychologists also investigate how groups function. Robert Zajonc's work on social facilitation showed that the presence of others enhances performance on easy tasks but hinders it on difficult ones. Irving Janis identified "groupthink" as a process leading to poor group decisions, while Muzafer Sherif's "Robber's Cave" study and Henri Tajfel's social identity theory illuminated the roots of intergroup conflict and prejudice.

7. Individual Differences: Measuring Intelligence and Personality Traits

The approach is quantitative and proceeds by constructing scales or tests. The use of quantitative methods to construct tests is known as the psychometric method.

Quantifying human variation. Differential psychology systematically studies how people differ, aiming to explain this complexity through a limited number of "traits." Sir Francis Galton, a pioneer in this field, applied statistical tools like the normal distribution and scatterplots to human characteristics, laying the groundwork for psychometrics, though his work was controversially linked to eugenics.

Measuring intelligence. Alfred Binet developed the first practical intelligence tests to identify children needing educational support, leading to the concept of "mental age" and later the Intelligence Quotient (IQ). Charles Spearman introduced "general intelligence" (g) and invented factor analysis, a statistical technique to identify underlying latent factors that explain patterns of test scores, revolutionizing the theoretical understanding of intelligence.

Mapping personality. The lexical approach, starting with dictionary words, was used by Gordon Allport and later Raymond Cattell to identify personality traits. Cattell's factor analysis led to his 16 Personality Factors (16PF). Hans Eysenck proposed a biogenic theory with three dimensions (Psychoticism, Extraversion, Neuroticism) linked to biological systems. Today, the "Big Five" (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism) is the dominant model, providing a robust framework for understanding personality.

8. Clinical Psychology: Diverse Paths to Mental Well-being

Whether we refer to ‘psychiatric illness’, ‘mental health’, ‘psychopathology’ or ‘psychological distress’, we are using terms that bring with them a whole set of assumptions and attitudes.

Understanding distress. Clinical psychology addresses psychological distress and mental health, distinct from psychiatry's medical model, which views distress as symptoms of underlying biological abnormalities. Diagnostic categories, rooted in Emil Kraepelin's work and formalized in the ICD and DSM, have evolved, reflecting changing societal understandings (e.g., removal of homosexuality as a disorder).

Therapeutic approaches. Early psychiatric treatments were often crude, but the 20th century saw the rise of drug treatments and "talking cures." Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis explored the unconscious mind, emphasizing early childhood experiences and repression. Post-Freud, various psychotherapies emerged, offering shorter, problem-focused treatments. Humanistic psychology, championed by Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, offered a more optimistic, person-centered approach, focusing on growth and self-actualization.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). Developed by Albert Ellis (Rational Emotive Therapy) and Aaron Beck, CBT integrates behavioral techniques with a focus on identifying and challenging dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs. It's a collaborative, present-focused, and goal-oriented therapy, highly effective for conditions like depression and anxiety, and widely recommended by health organizations today.

9. Professional Psychology: Applying Science to Real-World Challenges

Students who graduate with a degree in psychology have writing skills, research skills and data analysis skills that can be used in many different fields of work unrelated to psychology, including business, advertising, teaching and human resources.

Scientist-practitioner model. Professional psychology fields, guided by the scientist-practitioner model, integrate research and practice. This ensures interventions are evidence-based and that clinical outcomes inform further research, fostering a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement and ethical practice.

Diverse specializations. Psychology offers numerous professional pathways beyond clinical and counseling.

- Health Psychology: Investigates psychological and social aspects of illness, promoting well-being, addressing risky behaviors (e.g., smoking, obesity), and encouraging health-enhancing actions (e.g., exercise, screening uptake). The Health Belief Model helps understand health behaviors.

- Forensic Psychology: Applies psychological theories to the criminal justice system, preparing court reports, advising on reoffending risk, and researching eyewitness testimony (e.g., Loftus's misinformation effect).

- Educational Psychology: Works with children and young people in educational settings, assessing learning difficulties, advising on social-emotional problems, and developing strategies for inclusive education (e.g., Rosenthal's Pygmalion effect on teacher expectations).

- Occupational Psychology: Enhances workplace effectiveness, focusing on employee selection (using psychometrics), well-being, work design, training, leadership, and motivation (e.g., Hawthorne studies on worker participation).

- Sports Psychology: Improves performance in elite athletes and promotes exercise in the general population, addressing motivation, group dynamics, skill acquisition, and mental health benefits of physical activity (e.g., Triplett's social facilitation).

10. Future Directions: Navigating Challenges and Embracing Innovation

One of the key challenges that lies ahead will be to maintain ethical standards in the face of increasing demands to loosen them on the grounds of national security or political expediency.

Replication crisis and ethics. Psychology, like other sciences, faces a "replication crisis," where many published findings are difficult to reproduce, raising concerns about research validity and publication bias. This, alongside instances of data fabrication and ethical controversies (e.g., psychologists' involvement in "enhanced interrogation"), highlights the need for greater transparency, pre-registration of studies, and robust ethical oversight.

Positive psychology's rise. A growing trend is positive psychology, championed by Martin Seligman, which shifts focus from pathology to human strengths, well-being, and creativity. It develops interventions like "gratitude letters" and "three good things" exercises, aiming to build positive emotions and foster flourishing, often aligning with humanistic psychology's values.

Neuroscience and technology. Cognitive neuroscience, integrating systems neuroscience, computational neuroscience, and cognitive psychology, continues to advance rapidly with cheaper and more sophisticated brain imaging (fMRI, EEG). The future promises integration of psychological, physiological, and behavioral data through wearable technologies and ecological momentary assessment, enabling real-time monitoring of individuals and groups. However, this also raises significant concerns about privacy, data misuse (e.g., Cambridge Analytica scandal), and the potential for manipulation.

Last updated: