Key Takeaways

1. Defining Identity Amidst Racial Paradox

I am a Negro. My skin is white, my eyes are blue, my hair is blond. The traits of my race are nowhere visible upon me.

Invisible pigmentation. Walter White, with his white skin and European features, was often mistaken for white, a phenomenon known as "passing." This unique position allowed him to navigate both white and Black worlds, offering a rare perspective on racial dynamics. He acutely felt the "magic in a white skin" and the "tragedy, loneliness, exile, in a black skin," yet consciously chose to embrace his Negro identity.

Formative awakening. A pivotal moment occurred during the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot when, at thirteen, his family prepared to defend their home from a white mob. This violent expression of resentment against a neat Black family solidified his understanding of racial injustice. His father's quiet instruction to "don't shoot until the first man puts his foot on the lawn and then—don’t you miss!" ignited a profound awareness of his identity as a person to be hunted and discriminated against.

Conscious choice. Despite the option to live as white, White consciously insisted on his Negro identity, driven by a deep sense of belonging and a rejection of the hatred that fueled racial oppression. He realized that his appearance, which allowed him to "disassociate me from all the characteristics of the Negro" in the eyes of whites, also gave him a unique platform to challenge preconceived notions and fight for justice.

2. The Brutality of Mob Violence and Lynchings

I was sick with loathing for the hatred which had flared before me that night and come so close to making me a killer; but I was glad I was not one of those who hated; I was glad I was not one of those made sick and murderous by pride.

Horrific investigations. Walter White dedicated a significant part of his NAACP work to investigating lynchings, often risking his life by "passing" as white to gather firsthand accounts from the perpetrators. His early investigation into the Jim McIlherron burning in Estill Springs, Tennessee, revealed the casual cruelty and justifications for mob violence, where "any time a nigger hits a white man, he’s gotta be handled or else all the niggers will get out of hand."

Systemic injustice. These investigations consistently exposed the systemic failure of law enforcement and the judiciary to protect Black victims or prosecute white assailants. In the Phillips County, Arkansas, riot, over two hundred Black individuals were killed, and seventy-nine were indicted for murder, with trials dominated by armed mobs. White officials, like Governor Brough, often downplayed the violence or blamed "Northern agitators," while local authorities actively participated in or condoned the atrocities.

Propaganda and denial. The NAACP's "Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1918" study debunked the myth that most lynchings were for rape, revealing that "less than one-sixth of the victims of more than five thousand lynchings had been accused even by the mobs themselves of sex crimes." Despite irrefutable evidence, officials like Herbert Hoover initially denied reports of peonage during the 1927 Mississippi flood, where Black refugees were forced to work off "debts" for Red Cross aid. This pattern of denial and distortion highlighted the deep-seated prejudice that permeated society.

3. Fighting Disfranchisement and Securing the Vote

The disfranchised can never speak with the same force as those who are able to vote.

Long struggle. The NAACP waged a decades-long legal battle against various methods used to deny Black Americans the right to vote in the South, including "grandfather clauses," "white primaries," "understanding clauses," and poll taxes. These tactics also disfranchised many poor whites, leading to a political oligarchy where congressmen were elected by as little as "two to five per cent" of the potential electorate.

Landmark victories. Key Supreme Court cases gradually chipped away at these discriminatory practices. In Guinn v. United States (1915), the "grandfather clause" was struck down. Later, Nixon v. Herndon (1927) and Nixon v. Condon (1932) challenged the "white primary" by ruling that state-empowered party committees could not discriminate. Although Texas politicians continued to seek loopholes, the Smith v. Allwright (1944) decision finally affirmed that "the right to vote in such a primary for the nomination of candidates without discrimination by the State... is a right secured by the Constitution."

Persistent resistance. Even after these rulings, states like South Carolina attempted to evade the decisions by repealing all primary laws, as advocated by Governor Olin D. Johnston, who declared, "White supremacy will be maintained in our primaries. Let the chips fall where they may!" However, courageous judges like J. Waties Waring and John J. Parker ultimately upheld the constitutional right to vote, forcing Southern states to slowly integrate their electoral processes and empowering Black voters.

4. Challenging Educational Segregation

Second-class status must never be accepted, however long and difficult the attainment of first-class opportunity might be.

Unequal facilities. The NAACP launched a strategic legal attack on the gross inequalities in public education for Black and white students in segregated states. While the United States Supreme Court had on several occasions ruled that there was no discrimination per se in forcing Negroes to attend segregated schools as long as the facilities were equal, in practice, Black schools received significantly less funding, with the "average per capita expenditure for whites... around forty-five dollars a year and that for Negroes twelve dollars." This disparity extended to professional and graduate education, where Black students were often denied access entirely.

Legal precedents. Landmark cases like Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938) forced states to either provide equal law schools for Black students or admit them to existing white institutions. The Ada Lois Sipuel (1948) case further solidified this, with the Supreme Court ordering Oklahoma to "supply forthwith a legal education," leading to a ludicrous attempt by the state to create a makeshift "law school" in a capitol basement, which Miss Sipuel refused to enroll in.

Teacher salary equalization. Beyond student admissions, the NAACP also fought for equal pay for Black teachers, who were often paid significantly less than their white counterparts despite similar qualifications. Cases in Maryland and Virginia, including Alston v. School Board of Norfolk, successfully challenged these differentials, leading to millions of dollars in salary equalization. Judge Parker's characterization that such differentials were "as clearly discrimination on the ground of race as can be imagined" was of immeasurable value to the campaign.

5. Battling Discrimination in Employment and Housing

The program now being carried on through the Fair Employment Practice Committee to secure and protect the right to work without racial or religious discrimination must be continued and expanded during and after the war.

Wartime employment barriers. Despite desperate labor shortages during World War II, war plants largely remained closed to Black workers, leading to widespread bitterness. Philip Randolph's proposed March on Washington, supported by the NAACP, pressured President Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802, establishing the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC). This committee, though underfunded and facing intense opposition, made significant strides in opening employment opportunities based on ability.

Post-war setbacks. After the war, the FEPC was dismantled by congressional filibusters, and Black workers often faced downgrading or job loss as war industries closed. The United States Employment Service was returned to state control, further jeopardizing minority employment. This necessitated the creation of a labor department within the NAACP to continue the fight for fair employment practices.

Housing segregation. Beyond employment, housing discrimination remained a critical issue. After the Supreme Court outlawed segregation by city ordinances, "property owners in increasing numbers began to write into deeds clauses prohibiting the sale or rental to or occupancy by Negroes on pain of forfeiture or other monetary penalties." The NAACP tirelessly fought these covenants, arguing that government machinery, funded by all citizens, should not enforce private agreements that perpetuate racial segregation, culminating in a landmark Supreme Court decision in 1948 outlawing such covenants.

6. Exposing Military Segregation and Its Human Cost

No injustice embitters Negroes more than continued segregation and discrimination in the armed forces.

Widespread prejudice. Walter White's wartime role as a correspondent allowed him to witness firsthand the pervasive segregation and discrimination within the U.S. armed forces in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific. Black soldiers were routinely assigned to menial service units, denied promotions, and subjected to courts-martial for minor offenses, while white officers often exhibited blatant prejudice. This policy was maintained despite the country fighting against Nazi racial theories.

Combat effectiveness undermined. The transformation of combat-trained Black units, like the Second Cavalry Division in North Africa, into port battalions to unload ships, while white "misfits" remained idle, deeply demoralized Black troops. White officers often justified this by claiming Black soldiers were "no good in combat," a canard White disproved through investigations, such as the false accusations against the 93rd Division in Bougainville.

Moments of integration and its impact. Despite official policy, some instances of de facto integration, particularly during the Battle of the Bulge, proved the effectiveness of mixed units. White officers and enlisted men who fought alongside Black troops overwhelmingly reported positive experiences, with "seventy-seven per cent of the officers favored integration as contrasted with thirty-three per cent prior to the experience." However, after V-E Day, most Black platoons were returned to service roles, highlighting the Army's reluctance to maintain integration despite its proven success.

7. The Power of Political Engagement and Public Opinion

The Parker fight was recognized as the political coming of age of the hitherto-ignored Negro voters.

Strategic influence. The NAACP recognized the growing political independence of Black voters, particularly in pivotal Northern and border states, as a powerful tool for change. The successful opposition to the Supreme Court nomination of John J. Parker in 1930, due to his anti-Black stance, demonstrated that organized Black voters could influence national politics and hold senators accountable. This victory marked a shift from purely "moral victories" to tangible political success.

Presidential engagement. Walter White frequently engaged with presidents, from Roosevelt to Truman, advocating for civil rights legislation and executive action. While Roosevelt was often hesitant to challenge the Southern wing of his party on issues like anti-lynching bills, he was influenced by figures like Eleanor Roosevelt and the threat of mass protests, leading to the creation of the FEPC. Truman, initially feeling "helpless unless he is backed by public opinion," eventually established the President's Committee on Civil Rights, whose report, "To Secure These Rights," became a landmark document.

Shaping public discourse. Beyond direct political lobbying, the NAACP actively worked to shape public opinion through the press, radio, and alliances with influential figures. The Marian Anderson concert at the Lincoln Memorial, organized after the DAR denied her Constitution Hall, became a powerful symbol of democracy. Similarly, the Emergency Committee of the Entertainment Industry used radio broadcasts to counter mob violence, demonstrating the broad impact of cultural and media engagement.

8. The Global Dimension of Racial Injustice

We are concerned that this war bring to an end imperialism and colonial exploitation. We believe that political and economic democracy must displace the present system of exploitation in Africa, the West Indies, India, and all other colonial areas.

Interconnected struggles. Walter White's participation in the Pan-African Congress in 1921 and his travels abroad revealed the global implications of the race question, linking American racial prejudice to broader issues of colonialism, imperialism, and economic exploitation. He observed how European powers, while condemning injustice elsewhere, often maintained their own discriminatory colonial systems, as seen in H.G. Wells' "mote and beam" disease regarding British colonies.

Haiti's overlooked history. His visit to Haiti highlighted the hypocrisy of American foreign policy, which treated the Black republic shabbily despite its crucial role in American history (e.g., forcing Napoleon to sell the Louisiana Territory). He noted the stark contrast between the intellectual vibrancy of Haitian leaders, many educated at the Sorbonne, and the prejudice of American occupation officials who believed only they "understood Negroes."

UN and post-war hopes. At the founding of the United Nations in San Francisco, White, as a consultant, pushed for a human rights declaration and an end to colonialism. He was dismayed by the reluctance of the US delegation to address these issues directly, fearing it would undermine the moral leadership of the United States. The UN debate on Palestine partition further exposed racial arrogance, as some pro-partition advocates imperiously demanded votes from Black and poor nations like Haiti and Liberia.

9. Personal Sacrifices in the Fight for Justice

Life will mean much, much more to you when you are fighting for a cause than it possibly can if you stay here just to make money.

Early career choices. Walter White made significant personal sacrifices to join the fledgling NAACP, leaving a more financially secure path in insurance for a precarious future with a small, underfunded organization. His father, despite his own humble life, encouraged him, saying, "God will be using your heart and brains to do His will," while Dr. Louis T. Wright bluntly told him he'd "stagnate and eventually die mentally" if he stayed in Atlanta just for money.

Family's burden. His family often bore the brunt of his dedication. His mother, a meticulous homemaker, managed a large family on a "microscopic salary" and later faced threats due to his activism. His children, Jane and Walter Jr., encountered racial barriers in education and military service, with Walter Jr. being denied paratrooper enlistment because of his race and later facing the dilemma of being assigned to a "white" barracks.

Constant threats and emotional toll. White himself faced constant threats of violence, including plots by the KKK and attempts to frame him. The emotional toll of witnessing countless injustices, from lynchings to the degradation of his dying father in a segregated hospital, was immense. Yet, he clung to his father's dying words: "Human kindness, decency, love, whatever you wish to call it... is the only real thing in the world. It is a dynamic, not a passive, emotion. It’s up to you two, and others like you, to use your education and talents in an effort to make love as positive an emotion in the world as are prejudice and hate. That’s the only way the world can save itself. Don’t forget that. No matter what happens, you must love, not hate."

10. Enduring Hope for a Democratic Future

I am white and I am black, and know that there is no difference. Each casts a shadow, and all shadows are dark.

Signs of progress. Despite the pervasive nature of racial prejudice, Walter White observed significant, albeit incremental, progress over his three decades of activism. He noted that what seemed like "a dream of the millennium" twenty-five years prior were now facts:

- The University of Delaware admitted Black graduate students without segregation.

- Freehold, New Jersey, abolished segregated public schools.

- New Jersey abolished segregation in its National Guard.

- The Supreme Court unanimously outlawed restrictive covenants in real estate deeds in 1948.

Changing attitudes. He saw a growing number of white Americans, both North and South, actively supporting civil rights, often challenging deeply ingrained prejudices. The integration of officer training schools in the Deep South without friction, and the positive experiences of white soldiers fighting alongside Black troops, demonstrated that racial attitudes were not immutable. Publishers and editors also became more receptive to forthright writing about Black experiences.

Unwavering faith. At the core of his relentless fight was an unwavering faith in the democratic ideal and the inherent decency of humanity. He believed that racial prejudice was founded on an "absurd fallacy" – the belief in a basic difference between Black and white. His ultimate message, echoing his father's dying wish, was that "love, the positive force," must bind people together, recognizing that "there is no difference between the killer and the killed. Black is white and white is black."

Last updated:

Review Summary

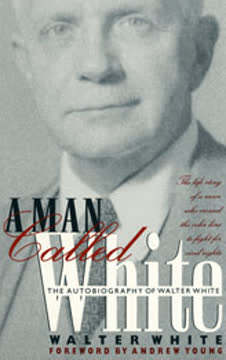

A Man Called White receives enthusiastic reviews, averaging 4.23 stars. Readers praise Walter White's autobiography for its powerful account of his NAACP work investigating lynchings while "passing" as white due to his light skin. Reviewers highlight stories of voter registration struggles, educational inequality, and the 1946 Columbia, Tennessee riot. Many found the book emotionally moving yet inspirational, appreciating its documentation of civil rights battles. Several recommend it as essential reading about pre-Civil Rights Movement activism, though availability is limited.