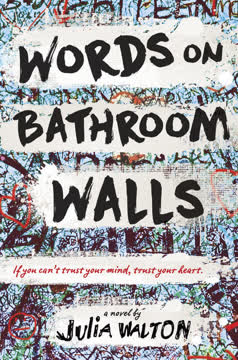

Plot Summary

Diagnosis and Denial

Sixteen-year-old Adam Petrazelli is diagnosed with schizophrenia, a revelation that upends his life and sense of self. He's forced into therapy and a clinical drug trial for ToZaPrex, a new antipsychotic. Adam resists the label and the process, feeling alienated from his family and terrified of what his diagnosis means. He's haunted by hallucinations—some benign, like Rebecca, and others menacing. Adam's internal monologue is laced with humor and self-deprecation, masking his deep fear of being "crazy." He clings to the hope that the drug might fix him, but he's skeptical of therapy and reluctant to let anyone, even his therapist, see his vulnerability. The chapter sets the stage for Adam's struggle: a battle between wanting to be normal and fearing he never will be.

New School, New Secrets

Adam's parents enroll him at St. Agatha's, a Catholic school where no one knows his secret. He's determined to keep his schizophrenia hidden, terrified of the stigma and secrecy and rejection he faced at his old school. Navigating the new environment is fraught with anxiety—he's hyper-aware of every glance and whisper, worried that his odd behaviors or hallucinations will give him away. Adam meets Dwight, a talkative, earnest classmate, and Maya, a sharp, guarded girl who quickly becomes important to him. The school's rituals and cliques are both a distraction and a source of stress. Adam's hallucinations persist, but the new drug gives him some distance from them, allowing him to observe rather than be consumed. Still, the pressure to appear normal is immense.

Hallucinations and Hope

As Adam's ToZaPrex dosage increases, he experiences fewer overwhelming hallucinations and gains some control over his mind. He learns to distinguish reality from delusion, though the visions—mobsters, a naked man named Jason, and the ever-present Rebecca—never fully disappear. The drug trial offers hope, but also side effects and uncertainty. Adam's journal entries to his therapist become a lifeline, a place to process his fears and small victories. He's cautiously optimistic, but aware that the drug is experimental and its effects may not last. The chapter explores the tension between hope for a cure and the reality of living with a chronic, stigmatized illness.

Meeting Maya

Maya enters Adam's life as a force of intellect and empathy. She's blunt, observant, and unafraid to challenge him. Their friendship grows through shared classes and Academic Team practices, where Maya's brilliance and Adam's memory make them a formidable pair. Maya senses Adam's struggles but doesn't pry, respecting his boundaries while offering support in her own way. Their bond deepens over time, evolving from camaraderie to romance. Maya becomes a stabilizing presence, someone who sees Adam beyond his illness. Their relationship is a source of joy and anxiety—Adam fears that revealing his secret will destroy the one good thing he's found.

The Drug Trial Begins

Adam's participation in the ToZaPrex trial is both a blessing and a burden. The drug grants him a semblance of normalcy, but the threat of side effects and the knowledge that it's temporary loom large. Therapy sessions remain silent, with Adam communicating only through his journal. He's acutely aware of the expectations placed on him by his family, doctors, and the school. The drug's effectiveness is measured not just in symptom reduction, but in Adam's ability to maintain relationships and function in daily life. The chapter highlights the precariousness of Adam's stability and the ever-present fear of relapse.

Navigating Friendship and Fear

Adam's friendships with Dwight and Maya deepen, but his secret creates distance. He's constantly on guard, afraid that any slip will expose his schizophrenia. Incidents at school—bullying from Ian, awkward social interactions, and the challenge of fitting in—test Adam's resolve. He finds solace in baking and Academic Team, activities that demand focus and offer a sense of accomplishment. The support of his mother and stepfather is both comforting and suffocating; their protectiveness reminds him of his fragility. Adam's internal struggle is mirrored in his relationships: he craves connection but fears rejection.

Family Tensions and Trust

Adam's diagnosis changes the dynamics at home. His mother is loving but anxious, his stepfather Paul supportive yet distant. The impending arrival of a new sibling adds complexity—Adam worries about being replaced or seen as a threat. Paul's mother is openly distrustful, fueling Adam's insecurities. The family's efforts to protect Adam sometimes feel like surveillance, eroding his sense of autonomy. Yet moments of genuine connection—shared meals, small acts of kindness—offer hope. The chapter explores the impact of mental illness on family roles, trust, and the longing for unconditional acceptance.

Academic Team and Acceptance

Academic Team becomes a haven for Adam, Maya, Dwight, and their friends. The group's quirky dynamics and shared pursuit of knowledge provide a sense of belonging. Adam's memory and Maya's analytical skills make them standouts, and their successes boost Adam's confidence. The team's acceptance of Adam, even without knowing his secret, is healing. Yet the pressure to perform and the fear of being exposed never fully abate. The chapter underscores the importance of community and the ways in which shared goals can bridge differences.

Love and Lies

Adam and Maya's relationship intensifies, moving from friendship to love. Their intimacy is both physical and emotional, offering Adam a glimpse of normalcy and happiness. Yet the foundation is shaky—Adam hides his illness, convinced that honesty will drive Maya away. The tension between authenticity and self-protection grows as their bond deepens. Adam's guilt over his deception is matched by his terror of losing Maya. The chapter captures the exhilaration and anxiety of first love, especially when shadowed by a life-altering secret.

Cracks in the Facade

The limits of ToZaPrex become apparent as Adam's symptoms resurface and side effects worsen. Stressors—academic pressure, family conflict, and the looming end of the drug trial—erode his control. Hallucinations become more intrusive, and Adam's ability to hide his illness falters. Incidents at school, including a public breakdown and a humiliating video, threaten to expose him. The fear of being unmasked intensifies, straining relationships and pushing Adam toward crisis. The chapter is a turning point, as the cost of secrecy and the fragility of Adam's stability are laid bare.

The Prom Disaster

Prom night, meant to be a milestone of normalcy, becomes a nightmare. Adam, desperate to maintain his facade, overdoses on his medication to stave off symptoms. At the dance, a video of his earlier breakdown is broadcast, orchestrated by Ian. Overwhelmed by hallucinations and panic, Adam loses control, injuring Maya and suffering a public psychotic episode. The aftermath is devastating: hospitalization, the end of the drug trial, and the shattering of Adam's relationships. The chapter is the emotional climax, where the consequences of secrecy, stigma, and untreated illness collide.

Hospital Walls and Healing

Adam is hospitalized, sedated, and forced to confront the reality of his illness. The loss of ToZaPrex means a return to more sedating, less effective medications. He's wracked with guilt over hurting Maya and the pain he's caused his family. Therapy resumes, now with more honesty and vulnerability. Adam's support system—his mother, Paul, Dwight, and eventually Maya—rallies around him, but trust must be rebuilt. The hospital becomes a place of reckoning, where Adam must accept both his limitations and his worth.

Facing the Truth

Adam finally tells Maya the truth about his schizophrenia, risking everything. Maya's reaction is complex—hurt, anger, but ultimately compassion. Their relationship is tested but not destroyed. Adam also confronts his own self-loathing and the internalized stigma that has shaped his actions. He learns that love and acceptance are possible, even when he feels most unlovable. The chapter is about the power of truth to heal, even when it hurts.

Rebuilding Connections

Adam's relationships begin to mend. Dwight remains steadfast, unfazed by Adam's diagnosis. Paul, once distant, steps up as a true father figure, defending Adam against prejudice and advocating for his right to belong. Even Ian, the antagonist, offers a clumsy apology. Adam's world, though changed, is not destroyed. He finds new ways to connect—with his family, friends, and himself. The process is slow and imperfect, but marked by moments of grace and understanding.

Sibling Bonds

The birth of Adam's baby sister, Sabrina, is a moment of joy and renewal. Holding her, Adam feels a sense of purpose and connection that transcends his illness. He worries about being a good brother, about the legacy of his diagnosis, but is reassured by the love and trust of his family. Sabrina's arrival symbolizes the possibility of new beginnings, even after trauma and loss.

Forgiveness and Moving Forward

Adam learns to forgive himself and others—Maya, for her anger; Paul, for his initial fear; even Ian, for his cruelty. He recognizes that everyone carries burdens and that forgiveness is essential for healing. Adam's journey is not about being cured, but about learning to live with uncertainty and imperfection. He embraces the messiness of life, finding meaning in small acts of kindness and connection.

Embracing the Unseen

Adam comes to terms with his hallucinations, no longer seeing them solely as enemies but as parts of himself. Rebecca, Rupert, Basil, and the others are not just symptoms, but manifestations of his fears, hopes, and creativity. With Maya's support, Adam learns to comfort his inner selves rather than punish them. He stops hiding from his illness, choosing instead to integrate it into his identity. The chapter is about self-acceptance and the ongoing work of living with mental illness.

Choosing to Live

The story ends not with a cure, but with a choice. Adam decides to keep living, to keep trying, even when the future is uncertain. He resumes therapy, continues his relationships, and finds meaning in everyday moments. The train metaphor—recurring throughout the book—becomes a symbol of possibility: adventure, death, or choice. Adam chooses adventure, however messy and unpredictable. The final message is one of resilience, hope, and the enduring power of love.

Characters

Adam Petrazelli

Adam is a sixteen-year-old boy grappling with early-onset schizophrenia. His voice is sharp, self-aware, and laced with humor, but beneath the sarcasm lies profound fear and loneliness. Adam's illness shapes every aspect of his life—his relationships, ambitions, and self-image. He's fiercely intelligent, with a photographic memory and a passion for baking, but struggles with trust and vulnerability. Adam's journey is one of self-acceptance: learning to live with his hallucinations, forgive himself for his limitations, and believe that he is worthy of love. His development is marked by setbacks and breakthroughs, culminating in a hard-won sense of hope.

Maya Salvador

Maya is Adam's classmate, Academic Team partner, and eventual girlfriend. She's analytical, pragmatic, and emotionally reserved, but deeply caring beneath her tough exterior. Maya's own family struggles—financial hardship, responsibility for younger siblings—make her mature beyond her years. She senses Adam's pain but respects his boundaries, offering support without pity. Maya's reaction to Adam's illness is complex: she's hurt by his secrecy but ultimately chooses to stand by him. Her love is not sentimental but steadfast, challenging Adam to be honest and accept himself.

Rebecca

Rebecca is Adam's most persistent hallucination—a beautiful, mute girl who comforts him in times of distress. She represents Adam's vulnerability, innocence, and longing for connection. Unlike his more menacing visions, Rebecca is a source of solace, teaching Adam to juggle and offering silent support. As Adam's self-acceptance grows, he learns to comfort Rebecca rather than fear her, symbolizing his integration of the illness into his identity.

Dwight Olberman

Dwight is Adam's first real friend at St. Agatha's. He's relentlessly positive, socially awkward, and unfazed by Adam's quirks. Dwight's acceptance is unconditional—he doesn't pry or judge, simply shows up, whether for Academic Team, tennis, or video games. His own family story (artificial insemination, overprotective mother) adds depth to his character. Dwight's steadfastness is a lifeline for Adam, demonstrating the power of friendship to transcend stigma.

Paul Tivoli

Paul is Adam's stepdad, a lawyer who initially struggles to connect with Adam after the diagnosis. His fear and protectiveness sometimes manifest as distance or over-caution, but he ultimately becomes Adam's fiercest advocate—defending him to the school, writing letters to the diocese, and claiming him as his son. Paul's journey mirrors Adam's: from fear to acceptance, from outsider to family.

Adam's Mother

Adam's mother is a constant presence—nurturing, worried, and fiercely devoted. She orchestrates Adam's treatment, advocates for his inclusion, and tries to shield him from pain. Her optimism is both a comfort and a source of pressure for Adam, who fears disappointing her. The arrival of a new baby tests her capacity for love and resilience, but she remains Adam's anchor.

Ian Stone

Ian is Adam's school ambassador and primary bully. Entitled, manipulative, and cruel, he targets Adam out of jealousy and a need for control. Ian's actions—especially broadcasting Adam's breakdown at prom—precipitate the story's climax. His eventual apology is awkward but sincere, hinting at his own insecurities and the possibility of change.

Hallucinations (Mobsters, Jason, Rupert, Basil)

Adam's hallucinations are varied: mobsters represent chaos and threat; Jason, the naked man, is oddly supportive; Rupert and Basil, British gentlemen, are sarcastic commentators. Each reflects aspects of Adam's fears, desires, and self-image. Over time, Adam learns to coexist with them, seeing them as parts of himself rather than enemies.

Sabrina

Adam's baby sister, Sabrina, is born near the story's end. Her arrival brings joy, purpose, and a sense of continuity. Holding her, Adam feels both the weight of responsibility and the possibility of redemption. Sabrina represents the future—uncertain, but filled with love.

Paul's Mother

Paul's mother embodies societal stigma and fear of mental illness. Her distrust and cruelty toward Adam highlight the challenges of living with an invisible, misunderstood condition. Her presence serves as a contrast to the acceptance Adam finds elsewhere.

Plot Devices

Journal-as-Narrative

The novel is structured as a series of journal entries written by Adam to his therapist. This device allows for intimate access to Adam's thoughts, unreliable narration, and a blend of humor and vulnerability. The journal format also mirrors Adam's struggle for control—he can edit, revise, and choose what to reveal, even as his illness resists containment.

Hallucinations as Characters

Adam's hallucinations are not just symptoms but fully realized characters, each with distinct personalities and roles. This device blurs the line between reality and delusion, inviting readers to empathize with Adam's experience. The hallucinations serve as both antagonists and allies, reflecting Adam's internal battles and growth.

The Drug Trial

The ToZaPrex trial is a central plot device, symbolizing the promise and peril of medical intervention. The drug's effectiveness, side effects, and eventual failure drive the story's tension. The trial's structure—dosage increases, monitoring, and eventual withdrawal—mirrors Adam's emotional journey from hope to despair to acceptance.

Foreshadowing and Symbolism

Trains recur as symbols of choice, adventure, and mortality. Windows represent Adam's shifting relationship with the outside world—closed in fear, opened in hope. Baking and food are metaphors for control, creativity, and connection, offering Adam a way to nurture others and himself.

Stigma and Secrecy

The need to hide his illness shapes Adam's actions and relationships. The fear of exposure—at school, with friends, in romance—creates suspense and ultimately leads to crisis. The public revelation at prom is the story's turning point, forcing Adam to confront the consequences of secrecy and the possibility of acceptance.

Analysis

Words on Bathroom Walls is a coming-of-age story that refuses easy answers or tidy resolutions. Julia Walton's novel challenges the stigma surrounding schizophrenia by giving voice to a protagonist who is self-aware, funny, and deeply human. The book explores the tension between the desire for normalcy and the reality of chronic illness, the pain of secrecy, and the healing power of honesty and connection. Through Adam's journey, readers witness the complexities of family, friendship, and first love—how they can both wound and heal. The novel's greatest strength is its refusal to reduce Adam to his diagnosis; instead, it insists on his full humanity, flaws and all. The message is clear: mental illness is not a moral failing, and those who live with it deserve understanding, dignity, and hope. In a world quick to judge and slow to listen, Adam's story is a call for empathy—and a reminder that everyone, no matter how broken they feel, is worthy of love.

Last updated:

FAQ

Synopsis & Basic Details

What is Words on Bathroom Walls about?

- A Teen's Secret Battle: Words on Bathroom Walls follows Adam Petrazelli, a witty and self-aware 16-year-old, as he navigates a new Catholic high school while secretly battling early-onset schizophrenia. Recently diagnosed, Adam is enrolled in a clinical drug trial for ToZaPrex, hoping it will suppress his vivid hallucinations and voices, allowing him to appear "normal."

- Love, Friendship, and Stigma: The narrative explores Adam's desperate attempts to conceal his illness from his new friends, especially Maya, a brilliant and guarded classmate who becomes his girlfriend, and Dwight, his loyal, quirky best friend. His journey is complicated by family anxieties, the pressures of a new environment, and the constant fear of exposure and rejection.

- Search for Self-Acceptance: Told through Adam's raw, humorous, and often heartbreaking journal entries to his therapist, the story delves into the psychological toll of living with a misunderstood mental illness. It's a poignant exploration of identity, the search for belonging, and the difficult path toward self-acceptance in a world quick to judge.

Why should I read Words on Bathroom Walls?

- Authentic Voice of Mental Illness: The novel offers a rare and deeply empathetic first-person perspective on living with schizophrenia, challenging stereotypes and fostering understanding. Adam's witty, self-deprecating narration makes his complex internal world accessible and relatable, even amidst his struggles.

- Compelling Character Development: Readers will be drawn into Adam's journey as he grapples with profound fear, loneliness, and the desire for normalcy, witnessing his growth from denial to a nuanced acceptance of his condition. His relationships with Maya, Dwight, and his family are beautifully rendered, showcasing the power of love and friendship.

- Thought-Provoking Themes: Beyond mental health, the book explores universal themes of identity, secrecy, the search for belonging, and the nature of reality. It prompts reflection on societal stigma, the ethics of treatment, and what it truly means to be "sane" or "broken," making it a powerful and memorable read.

What is the background of Words on Bathroom Walls?

- Contemporary American Setting: The story is set in a modern American context, specifically within a Catholic high school, which adds layers of institutional rules, religious symbolism, and a unique social environment for Adam to navigate. The school's strictures and the presence of nuns create a backdrop against which Adam's internal chaos is starkly contrasted.

- Focus on Mental Health Stigma: The narrative is deeply rooted in the cultural context of mental illness stigma, particularly surrounding schizophrenia. It highlights the fear, misunderstanding, and isolation experienced by individuals with such diagnoses, reflecting ongoing societal challenges in accepting and supporting those with mental health conditions.

- Exploration of Experimental Treatment: A significant plot element is Adam's participation in a clinical drug trial for an experimental antipsychotic, ToZaPrex. This aspect grounds the story in contemporary medical advancements and ethical considerations surrounding mental health treatment, showcasing both the hope and the potential dangers of new medications.

What are the most memorable quotes in Words on Bathroom Walls?

- "Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry, but why on earth should that mean that it is not real?": This quote, an allusion to Harry Potter, becomes a central philosophical anchor for Adam, encapsulating the novel's exploration of subjective reality and the validity of his internal experiences, regardless of whether others perceive them. It's a powerful statement on the nature of his illness and his eventual acceptance.

- "You lose your secrets when you let people get too close. That was the scariest thing for her when she started dating. I get it now. It's hard to let someone find you in all the dark and twisty places inside, but eventually, you have to hope that they do, because that's the beginning of everything.": This profound reflection from Adam reveals his deepest fear and his ultimate realization about vulnerability and connection. It marks a pivotal shift in his understanding of intimacy and the necessity of sharing his true self, even the "crazy" parts.

- "I'm sorry I'm crazy. Sorry I yelled at you. Sorry no one taught you how to make a sandwich. I'm sorry this isn't easier.": This all-encompassing apology to Paul, his stepfather, is a raw outpouring of Adam's guilt, self-blame, and the immense burden he feels his illness places on others. It's a moment of profound vulnerability that highlights his internal struggle and his yearning for acceptance despite his condition.

What writing style, narrative choices, and literary techniques does Julia Walton use?

- First-Person Journal Narrative: Walton employs a unique epistolary style, presenting the entire novel as Adam's journal entries to his therapist. This choice offers immediate, unfiltered access to Adam's internal monologue, allowing for a deeply personal and often unreliable perspective, crucial for understanding his subjective experience of schizophrenia.

- Witty and Self-Deprecating Tone: Adam's voice is characterized by sharp wit, sarcasm, and self-deprecating humor, which serves as a coping mechanism and a way to mask his profound fear and vulnerability. This tone makes heavy topics more digestible and creates a strong, engaging connection between Adam and the reader.

- Personified Hallucinations and Symbolism: Adam's hallucinations are not just symptoms but distinct characters (Rebecca, the mobsters, Jason, Rupert, Basil), externalizing his internal conflicts and emotions. Walton also uses recurring symbols like trains (choice, destiny), windows (connection to reality), and food/baking (control, nurturing) to deepen thematic meaning and foreshadow Adam's evolving mental state.

Hidden Details & Subtle Connections

What are some minor details that add significant meaning?

- Paul's Knuckle Cracking: This seemingly small habit, noted by Adam, subtly reveals Paul's internal anxiety and discomfort around Adam's illness. It's a non-verbal cue that Adam, despite his own struggles, keenly observes, highlighting the unspoken tension and fear that initially permeated their relationship, even as Paul tried to be supportive.

- The Bathroom Graffiti: The juxtaposition of "JESUS LOVES YOU" and "Don't be a homo" on the bathroom wall is a powerful, subtle commentary on the hypocrisy and conditional acceptance often found within religious institutions and society. Adam's later reflection on how a single word can twist meaning ("JESUS LOVES YOU BUT DON'T BE A HOMO") underscores his struggle with conditional acceptance and the judgment he fears.

- Rebecca's Evolving Role: Rebecca, Adam's benign hallucination, initially serves as a silent, comforting presence. Her later reactions, like crying when Adam is upset or hiding when he's overwhelmed, subtly mirror Adam's own emotional state and vulnerability, suggesting she is a manifestation of his inner child or his unexpressed feelings.

What are some subtle foreshadowing and callbacks?

- The Train Metaphor's Expansion: Initially introduced by a hallucination as meaning "adventure or death," the train metaphor subtly evolves throughout the narrative. Adam later reinterprets it to include "choice," foreshadowing his eventual agency in accepting his illness and choosing how to live, rather than being passively carried by fate or his condition.

- Great-Uncle Greg's Parallel: Adam's great-uncle Greg, who also exhibited symptoms of mental illness but was never diagnosed, serves as a subtle callback to the historical context of mental health and a foreshadowing of Adam's own potential future. Greg's kindness and acceptance by others, despite his "craziness," offers Adam a model for self-acceptance and the possibility of a fulfilling life.

- Maya's Perceptiveness: Early in their relationship, Maya's ability to "read" Adam's expressions and notice his "twitchiness" subtly foreshadows her eventual understanding of his illness. Her keen observation skills, initially a source of anxiety for Adam, later become a foundation for her unwavering support, as she sees beyond his facade.

What are some unexpected character connections?

- Dwight's Unconditional Acceptance: While Dwight is initially portrayed as a talkative, awkward classmate, his unwavering loyalty and acceptance of Adam, even after learning about his schizophrenia, is unexpectedly profound. His simple act of bringing a Wii to play tennis indoors, rather than abandoning their routine, demonstrates a deep, non-judgmental friendship that transcends Adam's fears.

- Paul's Transformation into a Father Figure: Paul, Adam's stepfather, initially struggles with fear and distance after Adam's diagnosis. However, his fierce defense of Adam to the Archdiocese, culminating in the powerful letter where he calls Adam "my son," reveals an unexpected depth of paternal love and commitment, solidifying their bond beyond mere legal ties.

- Ian's Complex Motivation and Apology: Ian, the primary antagonist, is revealed to be more than just a bully. His actions are partly driven by insecurity and jealousy (Adam being taller, better-looking). His awkward, coerced apology, and Maya's explanation of why she told him to bake cookies, reveal a subtle connection between their shared experiences of social pressure and Adam's impact on even his tormentor.

Who are the most significant supporting characters?

- Paul Tivoli (Stepfather): Paul's journey from anxious, somewhat distant stepfather to Adam's staunch protector and advocate is crucial. His letter to the Archdiocese, defending Adam's right to an education and calling him "my son," is a powerful emotional turning point, highlighting themes of unconditional love and overcoming prejudice.

- Dwight Olberman (Friend): Dwight represents unwavering, non-judgmental friendship. His consistent presence, talkative nature, and simple acceptance of Adam, even after learning about his schizophrenia, provide a vital anchor of normalcy and loyalty, demonstrating that true friendship can withstand profound challenges.

- Rebecca (Hallucination): More than just a symptom, Rebecca embodies Adam's inner vulnerability, innocence, and longing for comfort. Her silent presence, mirroring Adam's emotions and offering solace, is key to understanding his internal world and his eventual path toward self-compassion and integrating his illness.

Psychological, Emotional, & Relational Analysis

What are some unspoken motivations of the characters?

- Maya's Guardedness and Drive: Maya's "robot-like" pragmatism and intense focus on academics are unspoken coping mechanisms for her family's financial struggles and the burden of responsibility for her younger brothers. Her ambition to be a research doctor, not a patient-facing one, subtly reveals a desire for control and a distance from emotional messiness, which makes her eventual deep emotional connection with Adam even more significant.

- Ian's Insecurity and Need for Control: Ian's bullying of Adam, particularly his public humiliation at prom, is implicitly driven by his own insecurities as the "average height" son in a family of tall, successful brothers. His need to assert dominance and collect "information" about others stems from a desire for control in a world where he feels overshadowed, making Adam's perceived vulnerability a target.

- Adam's Self-Sabotage and Guilt: Adam's initial refusal to speak in therapy, his secrecy with Maya, and his later pushing her away are motivated by a deep-seated guilt and self-loathing. He believes he is "broken" and undeserving of love, fearing that his illness will inevitably hurt those he cares about, leading him to preemptively isolate himself to "protect" them.

What psychological complexities do the characters exhibit?

- Adam's Self-Awareness vs. Internalized Stigma: Adam possesses remarkable self-awareness, articulating his symptoms and fears with clarity and wit. However, this coexists with profound internalized stigma, where he views himself as "crazy" and a "monster," leading to a complex psychological battle between understanding his condition and accepting his worth.

- The Therapist's Evolving Role: The therapist, initially a silent recipient of Adam's journals, becomes a complex figure. Adam projects onto him, accusing him of being "smug" or "disappointed," but also acknowledges his persistence and eventual "anger at the universe." This dynamic reflects Adam's struggle with trust and his need for someone to witness his pain without judgment, even if he can't articulate it verbally.

- Paul's Fear and Protective Instincts: Paul's initial fear of Adam's illness is a complex psychological response, not of malice, but of the unknown and the potential threat to his family. His transformation into a fierce protector, willing to confront the school board, demonstrates a shift from fear-driven distance to unconditional love and acceptance, highlighting the psychological journey of a family member coping with mental illness.

What are the major emotional turning points?

- The Prom Disaster and Hospitalization: This event is the emotional climax, where Adam's carefully constructed facade shatters publicly. His psychotic episode, injuring Maya, and subsequent hospitalization force him to confront the devastating consequences of his secrecy and the severity of his illness, leading to profound guilt and despair.

- Paul's Letter to the Archdiocese: Discovering Paul's letter, where he passionately defends Adam and calls him "my son," is a powerful emotional turning point. It shatters Adam's belief that Paul is afraid of him and sees him as a burden, instead revealing a deep, unconditional love that helps Adam begin to heal his fractured sense of self.

- Maya's Confrontation and Declaration of Love: Maya's angry, yet ultimately loving, confrontation after Adam pushes her away is a critical emotional turning point. Her refusal to accept his self-sacrificing lies and her declaration of "I love you, too" despite knowing his truth, forces Adam to re-evaluate his belief that he is unlovable and undeserving of happiness.

How do relationship dynamics evolve?

- Adam and Maya: From Secrecy to Shared Vulnerability: Their relationship evolves from a cautious friendship, built on mutual respect and intellectual connection, to a deep romantic bond shadowed by Adam's secret. The prom disaster forces a painful truth, but Maya's choice to stay and fight for their relationship transforms it into one of shared vulnerability and unconditional love, where she actively supports his healing.

- Adam and Paul: From Distance to Paternal Bond: Initially, Paul's fear of Adam's illness creates a palpable distance, making Adam feel like a "monster." However, Paul's unwavering support, culminating in his powerful letter to the Archdiocese and his presence during Adam's hospitalization, transforms their dynamic into a genuine father-son relationship, built on protection, understanding, and love.

- Adam and His Hallucinations: From Antagonism to Integration: Adam's relationship with his hallucinations shifts from a desperate struggle to suppress them to a more nuanced acceptance. With Maya's guidance, he learns to comfort Rebecca and acknowledge the others as parts of himself, moving towards integration rather than outright rejection, signifying a crucial step in his self-acceptance.

Interpretation & Debate

Which parts of the story remain ambiguous or open-ended?

- The Nature of Rebecca's Reality: While Adam eventually acknowledges his hallucinations aren't "real" in the conventional sense, Rebecca's unique role as a comforting, silent presence, and Adam's continued interaction with her even after accepting his illness, leaves her reality somewhat ambiguous. Is she purely a symptom, or a profound manifestation of Adam's inner self that he chooses to embrace as "real" to him? This challenges the reader's perception of reality itself.

- The Long-Term Efficacy of Treatment: The novel ends with Adam off ToZaPrex and on new, more sedating medication, with no clear "cure." The future of his treatment and his ability to manage his symptoms remains open-ended. The story emphasizes that living with schizophrenia is an ongoing journey, not a problem with a definitive solution, leaving readers to ponder the continuous effort required for stability.

- The Therapist's True Intentions: Adam frequently questions his therapist's motivations, wondering if he's "smug," "disappointed," or simply trying to "fix" him. The therapist's silent presence and eventual written communication ("Angry... At the universe") maintain a degree of ambiguity about his personal feelings and the true impact of his sessions, allowing readers to interpret the therapeutic relationship through Adam's subjective lens.

What are some debatable, controversial scenes or moments in Words on Bathroom Walls?

- Adam's Overdose and Prom Incident: Adam's decision to hoard and overdose on ToZaPrex to attend prom, leading to his public breakdown and Maya's injury, is highly debatable. While driven by a desire for normalcy and fear of disappointing Maya, it highlights the dangerous consequences of self-medication and secrecy, sparking discussion on personal responsibility versus the overwhelming nature of mental illness.

- The "JESUS LOVES YOU / Don't be a homo" Graffiti: This seemingly minor detail on the bathroom wall, and Ian's later comment echoing its sentiment, is controversial. It directly confronts the hypocrisy and conditional acceptance within religious institutions and society, forcing readers to grapple with prejudice and the painful reality of judgment faced by marginalized individuals, including those with mental illness.

- Maya's "Tough Love" Approach: Maya's bluntness and refusal to "sugarcoat" the realities of Adam's illness or the challenges of having children, while ultimately helpful, can be seen as controversial. Her pragmatic, almost clinical approach ("This is your kid," "They get rewarded for not shitting their pants") challenges conventional notions of empathy and comfort, prompting debate on the most effective ways to support someone with mental illness.

Words on Bathroom Walls Ending Explained: How It Ends & What It Means

- Acceptance of Ongoing Struggle: The ending of Words on Bathroom Walls is not a "cure" but a profound acceptance of Adam's ongoing journey with schizophrenia. He is off the experimental drug ToZaPrex and on new medication, acknowledging that he "might never be okay." This signifies a shift from seeking a magical fix to embracing the reality of a chronic condition, highlighting themes of resilience and living with uncertainty.

- Embracing His "Corporeally Challenged" Friends: Adam redefines his hallucinations as "corporeally challenged" friends, no longer viewing them solely as enemies but as parts of himself. With Maya's support, he learns to comfort Rebecca and integrate these internal experiences, symbolizing a crucial step in self-acceptance and reducing the internal battle against his own mind.

- Choosing Life and Connection: The final lines, "Alas, adventure calls, Doc. It's been real. But actually, I've got a train to catch. See you on Wednesday, right?", reinterpret the recurring train metaphor as a symbol of choice and continued engagement with life. Adam chooses to live, to maintain his relationships (with Maya, Dwight, Paul, and even his therapist), and to face the future, however unpredictable, with a newfound sense of agency and hope.

Review Summary

Words on Bathroom Walls is a highly praised novel about a teenager with schizophrenia. Readers appreciate the honest, humorous portrayal of mental illness and the well-developed characters, particularly the protagonist Adam. The book offers insight into living with schizophrenia, challenging stereotypes and stigma. Many reviewers found it emotionally impactful and educational. While some criticized certain aspects of the portrayal or writing style, most considered it an important, eye-opening read. The romance subplot and supportive relationships were also highlighted as strengths.

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.