Key Takeaways

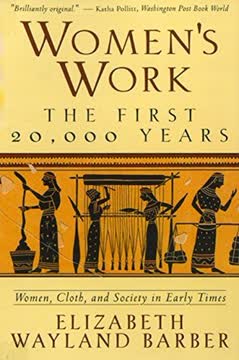

1. Textiles: The Quintessential Women's Work for Millennia

If the productive labor of women is not to be lost to the society during the childbearing years, the jobs regularly assigned to women must be carefully chosen to be “compatible with simultaneous child watching.”

Childcare compatibility. For millennia, textile production—spinning, weaving, and sewing—became women's primary craft due to its unique compatibility with childcare demands. Unlike hunting, smithing, or deep-sea fishing, these tasks did not require rapt concentration, were easily interruptible and resumable, posed minimal danger to children, and could be performed close to home. This fundamental division of labor ensured women's continuous contribution to society even during their childbearing years.

Time-consuming craft. Before the Industrial Revolution, making cloth for a family was incredibly time-consuming, often consuming as many labor hours as producing food. Women spun while watching children, girls spun while tending sheep, and both spun while traveling, utilizing every spare moment. This constant engagement meant little time or resources for experimentation, explaining why major textile innovations like the spinning jenny were often invented by men, who had more leisure for such endeavors.

Enduring traditions. Despite modern industrialization moving textile work out of the home, the core association of women with fiber crafts persists in many cultures. The rhythmic, non-strenuous nature of spinning and knitting still makes them satisfying hobbies compatible with child-watching, echoing ancient practices. This deep-rooted tradition highlights the enduring influence of early societal structures on gender roles and daily life.

2. The "String Revolution" Transformed Early Human Life

So powerful, in fact, is simple string in taming the world to human will and ingenuity that I suspect it to be the unseen weapon that allowed the human race to conquer the earth, that enabled us to move out into every econiche on the globe during the Upper Palaeolithic.

Palaeolithic innovation. Around 20,000 to 30,000 years ago, the invention of twisting weak fibers into long, strong string marked a "String Revolution" in the Upper Palaeolithic. This humble yet crucial discovery, inferred from the appearance of needles and small-holed beads for sewing, enabled humans to create snares, fishlines, carrying nets, and to bind objects, vastly improving survival and expansion into new environments. The earliest preserved example, a three-ply cord from Lascaux Cave (ca. 15,000 B.C.), demonstrates advanced skill.

Symbolic clothing. Early string was also used for symbolic clothing, most notably the string skirt, depicted on Palaeolithic "Venus figures" from France and Russia. These skimpy, non-functional garments, often emphasizing fertility, persisted for millennia, appearing in Neolithic figurines and Bronze Age burials. Their enduring presence suggests a deep cultural significance, possibly marking women of childbearing age or marital status.

Linguistic echoes. The symbolic function of the string skirt is echoed in later traditions and language. Homer's "girdle of a hundred tassels" worn by Hera to seduce Zeus, and the Greek zostra (a red wool girdle) used as a fertility charm in modern Greece, link directly to this ancient garment. This continuity across 20,000 years, from Palaeolithic carvings to modern folk costumes, underscores the profound and lasting cultural impact of women's early textile innovations.

3. Neolithic Settlements Fostered Communal Textile Arts

In such a world the women could bring their smaller crafts out into the communal yard in good weather, to chat together and help one another as they worked and watched the children play.

Sedentary life's impact. The shift to permanent settlements in the Neolithic (ca. 10,000 B.C.) profoundly changed women's lives, enabling closer child spacing and the accumulation of possessions. This sedentary lifestyle fostered communal work, particularly in horticulture, where women managed garden plots and fiber crafts while children played nearby. This "courtyard sisterhood" allowed for shared labor, mutual support, and the transmission of skills across generations.

Loom development. The need for larger quantities of cloth in settled communities spurred the invention of more efficient looms. Two main types emerged:

- Horizontal ground loom: Spread south and southeast from the Near East, ideal for hot, dry climates.

- Warp-weighted loom: Spread north and west across Europe, suitable for indoor use in colder, wetter climates.

These innovations, likely derived from simpler band looms, allowed for the production of wider fabrics and were predominantly operated by women.

Textiles as art. Despite being subsistence-level economies, Neolithic European textiles were astonishingly ornate, reflecting a deep investment of time beyond mere utility. Examples from Swiss lake dwellings (3000 B.C.) show elaborate stripes, checkers, triangles, and braided fringes, often in multiple colors. This "extravagance" stemmed from a different perception of time (not "money") and the belief that decorating objects with efficacious symbols could promote life, prosperity, and safety, making "art" both pleasing and functional.

4. Bronze Age Innovations Elevated Textiles to High Art and Commerce

By how much the Phaiakian men are expert above all other men in propelling a swift ship on the sea, by thus much their women are skilled at the loom, for Athena has given to them beyond all others a knowledge of beautiful craftwork, and noble intellects.

Wool's transformative power. The introduction of wool from woolly sheep (ca. 3500 B.C.) revolutionized textile arts in the Bronze Age, particularly in the Aegean. Unlike flax, white wool was easy to dye, and its natural variations in color (black, gray, brown, white) enabled vibrant patterned textiles. This new fiber, combined with "Island Fever" (intense cultural investment in isolated societies), allowed Minoan women on Crete to pour unprecedented energy into creating beautiful, colorful cloth.

Minoan textile mastery. Evidence from sites like Myrtos (2300 B.C.) shows extensive flax and wool processing, spinning, weaving, and dyeing. Minoan frescoes (1900-1400 B.C.) depict women in elaborate flounced skirts and open bodices, adorned with intricate patterns like heart-spirals, rosettes, and zigzags, in bright reds, blues, and yellows from madder, woad, and murex snails. These textiles were not just for local use but became valuable exports, traded to places like Egypt.

Homeric reflections. Homer's Odyssey offers a vivid, albeit idealized, glimpse into this horticultural society, where women like Queen Arete held significant power, arbitrated disputes, and controlled the household. The description of her spinning sea-purple wool and her fifty serving women grinding grain and weaving highlights the central role of women in textile production and food preparation, mirroring archaeological findings of Minoan life.

5. Clothing Served as a Complex Social and Magical Code

A few candid souls may, as the saying goes, wear their hearts on their sleeves, but we all wear a great deal of our pedigree and social aspirations written all over our apparel.

Beyond utility. Clothing, from its earliest forms, functioned as a sophisticated visual language, continuously conveying social messages beyond mere warmth or modesty. It marked:

- Sex, age, marital status: String skirts, specific headgear.

- Wealth, rank: Royal purple robes, gold jewelry.

- Ritual participation: Sacred knots, special veils.

This silent communication system was crucial in societies where literacy was rare, making clothing a primary medium for social information.

Recording history and myth. Textiles also served as mnemonic devices and historical records. Helen of Troy is depicted weaving the struggles of the Trojan War into her purple cloth, and Athenian women wove the battle of gods and giants into Athena's annual peplos. The Bayeux Tapestry, depicting the Norman Conquest and Halley's Comet, further illustrates this tradition of using cloth to immortalize significant events and myths.

Invoking magic. Many clothing elements were imbued with magical properties to promote fertility, prosperity, or protection. Hooked lozenges on Balkan aprons symbolized female fertility, while red embroidery at garment openings was believed to ward off illness-causing demons. Myths of "dragon's blood" poisoned clothes (arsenic-dyed fabrics) and "magic nettle shirts" (finely woven nettle fiber) reveal how real-world phenomena were transformed into fantastical tales when their origins were forgotten.

6. Near Eastern Empires Centralized Textile Production, Empowering Some Women

Women of the merchant class were not the only ones running textile establishments. Queens did it, too, but for the “state” rather than directly for themselves.

Economic transformation. The "secondary products revolution" (ca. 4000 B.C.), exploiting animals for milk, wool, and muscle power, profoundly reshaped Near Eastern societies. While men dominated large-scale agriculture with plows, women's roles shifted to dairy farming, grain grinding, and textile production. This era saw the rise of palace-controlled workshops and trade caravans, creating new economic opportunities and challenges for women.

Women as entrepreneurs. In Old Assyrian trade (ca. 1900 B.C.), women like Lamassi and Waqartum were active textile entrepreneurs. They managed production, negotiated with caravan drivers, and handled finances, often complaining when their husbands delayed payments. These women owned property, engaged in commerce, and ran households, demonstrating a degree of economic independence despite patriarchal legal frameworks.

Palace workshops and slavery. Royal women, like Queen Iltani of Karana, managed large palace textile workshops, employing dozens of women (and some men) who spun and wove. Many of these workers were captives of war, reflecting the rise of slavery as a means of labor acquisition. These centralized systems produced vast quantities of cloth for royal gifts, internal consumption, and trade, with men often handling ancillary tasks like dyeing or finishing.

7. Mycenaean and Greek Societies Redefined Women's Textile Roles

Captive women undoubtedly wove the mass of towels and bed sheets, cloaks and blankets, tunics and chemises used by the ruling household and its many dependents, plus extras for the guests and the export trade.

Mycenaean control. The Mycenaean Greeks (ca. 1600-1200 B.C.) established a highly centralized, palace-controlled textile industry, primarily relying on captive female labor. Women were specialized into distinct tasks—combers, spinners, warpers, weavers, seamstresses—with each group working separately, connected only by palace administration. This system maximized control over a large, dependent workforce, producing massive quantities of wool textiles for domestic use, gifts, and export.

Shifting status. The Mycenaean conquest of Crete saw a dramatic shift in clothing and status. Minoan men adopted elaborate patterned textiles, while Minoan women's dresses became plainer. This reflected the conquerors' appropriation of existing luxury goods and the subsequent decline in the production of complex fabrics under a quota-driven labor system. In later Classical Athens, women's status further declined, with "free" women largely confined to the home, their textile work limited to household needs or religious offerings.

Myths and goddesses. Greek mythology reflects the profound cultural significance of textiles and women's roles. The Moirai (Fates) spun the thread of life, and Aphrodite, goddess of procreation, was depicted spinning. Athena, goddess of weaving and "civilization," embodied human skill and cunning, with stories like her contest with Arachne highlighting the importance of the craft. These myths underscore the deep connection between women, creation, and destiny in the ancient Greek worldview.

8. Unearthing Invisible Histories Requires Diverse and Creative Research Methods

A hypothesis, after all, is no better than the evidence that supports it, and hypotheses without evidence are mere wishful thinking.

Beyond conventional sources. Reconstructing the history of perishable commodities like cloth and women's work demands innovative research methods beyond traditional archaeology and texts. Early archaeologists often discarded textile fragments or loom weights, deeming them valueless. However, meticulous recording, scientific analysis (radiocarbon dating, chemical analysis of dyes), and interdisciplinary approaches have revealed a wealth of information.

Interdisciplinary tools. Key methods include:

- Linguistic analysis: Tracing word origins (e.g., "tunic," "shirt," "ret") to understand technological and cultural diffusion.

- Comparative reconstruction: Applying linguistic methods to cultural conventions like clothing styles and decorative patterns to trace their historical evolution.

- Ethnography: Studying parallel behaviors in modern traditional cultures to suggest possibilities for ancient practices (e.g., Bedouin weaving, Hopi pottery).

- Experimental archaeology: Replicating ancient crafts (e.g., weaving Hallstatt plaid, making loom weights) to understand practical challenges and techniques.

Recognizing absence. A crucial, yet difficult, aspect of this research is identifying what isn't there. For example, the absence of distaffs in Egyptian spinning depictions, despite long fibers, revealed that Egyptians spliced rather than draft-spun flax. This "Sherlock Holmes" approach, focusing on missing elements, can uncover fundamental assumptions and lead to entirely new insights about ancient life and technology.

Last updated:

Review Summary

Women's Work by Elizabeth Wayland Barber explores textile production and women's roles from the Paleolithic to Iron Age. Readers praise Barber's engaging writing, interdisciplinary approach combining archaeology, linguistics, and practical weaving knowledge, and her ability to answer long-standing questions about women's history. The book focuses primarily on Bronze Age Europe, Egypt, and the Aegean. Some criticize it as dated, repetitive, and occasionally problematic in interpretations. Reviewers appreciate learning how textiles reveal social history and women's labor, though some find it dry or poorly organized. Most recommend it for anyone interested in textile history, archaeology, or women's contributions to early societies.