Plot Summary

No Mirrors, No Windows

In a post-apocalyptic convent, the narrator describes a world stripped of mirrors and windows, where the only way to see oneself is through the eyes of others, and the past is a blur. The House of the Sacred Sisterhood is a fortress of ritual, discipline, and fear, ruled by the enigmatic Superior Sister and the unseen "He." The narrator, a young woman, writes in secret, hiding her words and her true self. The atmosphere is one of claustrophobia, suspicion, and violence, where cruelty is both a survival tactic and a form of worship. The absence of reflection is both literal and metaphorical: the women are denied self-knowledge, history, and hope, forced to live in a perpetual present of obedience and punishment.

Rituals of Blood and Song

The Sacred Sisterhood's life is structured by brutal rituals: Minor Saints, their eyes sewn shut, sing incomprehensible hymns in a language only the Chosen understand. Blood is both a symbol and a tool—spilled in ceremonies, used as ink, and tasted as a sacrament. The narrator is both fascinated and repulsed by the violence, longing for the power of the Chosen but fearing the mutilations that come with it. The ceremonies are designed to erase individuality and enforce submission, with the Superior Sister and "He" wielding absolute authority. The narrator's secret writing becomes an act of resistance, a way to remember and to imagine another life.

The House of the Sacred Sisterhood

The House is a closed ecosystem, divided into rigid castes: the Enlightened, the Chosen (Minor Saints, Full Auras, Diaphanous Spirits), the unworthy, and the nameless servants. Each group is marked by physical mutilation or ritual purity. The narrator dreams of becoming Enlightened, not Chosen, to avoid the loss of tongue or sight. The Superior Sister enforces discipline with whips and exemplary punishments, while "He" remains a distant, godlike figure. The House is haunted by the ghosts of monks, the memory of a world destroyed by ecological collapse, and the constant threat of contamination from the outside. The narrator's longing for connection and meaning is stifled by the oppressive order.

Haze and Sacrifice

A deadly haze descends, forcing the Sisterhood into ever more extreme sacrifices: fasting, self-flagellation, and bloodletting. The haze is both a literal threat and a metaphor for the suffocating atmosphere of the House. The Enlightened interpret the haze as a divine test, demanding greater submission. The narrator's body becomes a site of both suffering and resistance, as she writes with her own blood and dreams of escape. The haze exposes the fragility of the Sisterhood's world, the arbitrariness of its rules, and the desperation of its faith. The phrase "Without faith, there is no refuge" becomes both mantra and curse.

Cricket Bread and Contamination

Food is scarce and tainted: the unworthy eat crickets in endless forms, while the Enlightened and Chosen receive the few uncontaminated fruits and vegetables. The narrator describes the rituals of trapping animals, the fear of contamination, and the hierarchy of suffering. The arrival of a wanderer from the outside is met with suspicion and ultimately death, reinforcing the House's isolation. The story of a woman who hid a man and was brutally punished reveals the cost of compassion and the impossibility of escape. The narrator's own past as a wanderer is fragmented, marked by trauma and the kindness of Helena, who paid with her life for her disobedience.

The Arrival of the Wanderer

The appearance of a new wanderer—starving, mute, and possibly contaminated—triggers a cycle of suspicion, quarantine, and death. The House's rules are absolute: men are killed on sight, children and the elderly are never seen. The narrator recalls her own arrival, saved by Helena's compassion, and the subsequent betrayal that led to Helena's burial among the heretics. The fate of the wanderer is a warning: survival depends on submission, and mercy is punished. The House's rituals of purification are both a shield against the outside world and a prison for those within.

Helena's Compassion, Helena's Fate

Helena, the narrator's first protector and perhaps her first love, is remembered with a mixture of longing and guilt. Her compassion—saving the narrator, sharing forbidden words and touch—marks her as a heretic. When the narrator's secret writings about Helena are discovered, she betrays Helena to save herself. Helena is buried alive, her name erased, her grave unmarked. The narrator's grief is complicated by shame and the knowledge that in the House, love is always dangerous, always punished. The memory of Helena haunts the narrator, shaping her longing for connection and her fear of exposure.

The Minor Saint's Funeral

The death of a Minor Saint is both tragedy and celebration: a rare chance for the unworthy to eat well, to participate in rituals of mourning and purification. The funeral is a spectacle of beauty and decay, with the body exposed to the elements in the Tower of Silence, denied burial to preserve its purity. The narrator's desire for the sacred crystal buried with the Saint leads her to the tower at night, where she encounters a mysterious figure—Lucía, the deer. The funeral becomes a turning point, a moment of revelation and the beginning of a new, forbidden bond.

The Deer Named Lucía

Lucía, a wanderer with an otherworldly presence, arrives at the House, her beauty and strangeness marking her as a candidate for Chosen or Enlightened. The narrator is drawn to her, sensing both danger and possibility. Lucía's arrival disrupts the fragile balance of power, provoking jealousy, suspicion, and desire. Her submission during the renaming ceremony is perfect, but her difference is undeniable. The narrator vows to protect her, even as the House's rituals threaten to consume them both. Lucía becomes a symbol of hope, change, and the possibility of love in a world built on fear.

Lucía's Trial by Fire

When acid rain threatens, Lucía volunteers to walk on burning embers—a sacrifice no one has dared before. She emerges unscathed, her feet untouched by fire, and the House is thrown into confusion. Some see a miracle, others a trick. Lucía's power, or the perception of it, makes her both revered and feared. The narrator's love deepens, but so does the danger: Lucía is now a target for both adoration and destruction. The House's need for miracles is matched only by its capacity for violence against those who provide them.

The Witch and the Wasps

Lucía is accused of witchcraft after surviving an attack by wasps, which instead turn on her enemies. The rumor spreads: Lucía is a witch, a cockroach, a lover of demons. The narrator and Lucía find solace in each other, their love a secret rebellion. The House's cruelty intensifies, with punishments escalating and the Superior Sister's rage growing. The boundaries between miracle and monstrosity blur, as nature itself seems to respond to Lucía's presence. The narrator's writing becomes both confession and testimony, a record of love and resistance.

Forbidden Love in the Thicket

In the hidden hollow of a tree, the narrator and Lucía consummate their love, surrounded by fireflies—a miracle in a dying world. Their union is both an act of defiance and a brief escape from the House's violence. The truth, Lucía whispers, is a sphere containing both reality and lies. Their love is fragile, threatened by jealousy, rumor, and the ever-present gaze of the Superior Sister. Yet in the thicket, they find a fleeting sense of wholeness, a glimpse of another world. The narrator's longing for Lucía becomes the axis of her existence.

Circe, the Enchantress

The narrator recalls her life before the House: a world of hunger, violence, and fleeting kinship among the "tarantula kids." Her closest companion was Circe, a feral cat she names after the mythic sorceress. Together they survive, scavenging, hiding, and fleeing from predatory adults. The memory of Circe's death—killed by men in a metallic woods—haunts the narrator, shaping her fear, her capacity for love, and her need to write. Circe's loss is both a personal wound and a symbol of the world's collapse, the price of survival in a world without mercy.

The Metallic Woods

In a landscape of artificial trees and infertile earth, the narrator is attacked and raped by a group of men. Circe is killed trying to defend her. The trauma is unspeakable, the pain inescapable. The narrator buries Circe by a dead river, her grief and rage transforming her into the survivor who will eventually reach the House. The metallic woods are a place of ultimate loss, where the last illusions of safety and innocence are destroyed. The memory of this violence shapes the narrator's understanding of power, vulnerability, and the need for solidarity.

The Truth is a Sphere

In the aftermath of trauma and love, Lucía tells the narrator that the truth is a sphere, always containing a lie at its core. This insight becomes a lens through which the narrator views the House, its rituals, and her own desires. The boundaries between miracle and trick, faith and delusion, love and betrayal, are always shifting. The narrator's writing becomes an attempt to capture the fleeting, contradictory nature of truth, to bear witness to both suffering and beauty. The sphere of truth is both a prison and a possibility.

The Death of Lourdes

Lourdes, the narrator's rival and tormentor, is killed by the Superior Sister after a failed attempt to harm Lucía. Her body is left hanging as a warning, then secretly buried by the narrator and Lucía. The House's violence turns inward, consuming its own. The narrator's feelings toward Lourdes are complex: hatred, pity, and a recognition of shared vulnerability. The cycle of punishment and revenge escalates, with the Superior Sister seeking new victims. The narrator's love for Lucía becomes both a refuge and a source of danger.

The New Enlightened

Lucía is chosen as the new Enlightened, separated from the narrator and taken to the forbidden Refuge. The narrator's grief is overwhelming, her sense of purpose shattered. The ceremony is both beautiful and terrifying, a spectacle of submission and erasure. The narrator's longing for Lucía becomes a form of resistance, fueling her determination to rescue her lover. The House's rituals are revealed as both a means of survival and a mechanism of control, designed to break the spirit and enforce obedience. The narrator's writing becomes a lifeline, a way to hold on to memory and hope.

Escape and the Book of the Night

In a final act of defiance, the narrator breaks into the Refuge, discovering the truth behind the House's rituals: abuse, exploitation, and the emptiness of the supposed miracles. Wounded but determined, she helps Lucía and others escape through the hole in the wall, sacrificing herself to buy them time. The narrator's last act is to hide her secret writings—the "book of the night"—in the hollow of the tree, hoping that one day someone will find them and remember. Her story ends in blood and hope, a testament to the possibility of love and resistance in a world built on violence and forgetting.

Characters

The Narrator

The unnamed narrator is the emotional and psychological center of the novel. Scarred by trauma, loss, and betrayal, she is both a product and a critic of the House's violence. Her secret writing is an act of resistance, a way to remember who she was before the House and to imagine a different future. Her relationships—with Helena, Circe, and Lucía—reveal her longing for connection, her capacity for love, and her fear of exposure. She is both complicit in and critical of the House's rituals, torn between the desire for acceptance and the need for truth. Her journey is one of self-discovery, culminating in sacrifice and the hope of liberation for others.

Lucía (The Deer)

Lucía arrives as a wanderer, marked by beauty, strangeness, and an aura of the miraculous. She quickly becomes a candidate for Chosen or Enlightened, her presence disrupting the House's fragile order. Lucía's apparent immunity to fire, her power over wasps, and her capacity for love make her both revered and feared. Her relationship with the narrator is a source of hope and danger, a forbidden love that challenges the House's rules. Lucía's ultimate ascension as Enlightened is both a victory and a loss, as she is separated from the narrator and subjected to the House's violence. She embodies the possibility of change, the power of nature, and the resilience of the human spirit.

The Superior Sister

The Superior Sister is the House's chief disciplinarian, wielding whips, punishments, and fear to maintain order. Her past is shrouded in rumor—climate migrant, war survivor, possible sibling to "He." She is both admired and feared, her strength and cruelty legendary. The Superior Sister's relationship to the narrator and Lucía is complex: she is both a rival and a gatekeeper, enforcing the rituals that shape their lives. Her violence is both personal and systemic, a reflection of the House's need for control. In the end, she is revealed as complicit in the House's deepest abuses, her power both absolute and ultimately vulnerable.

"He"

"He" is the House's ultimate authority, a figure both present and absent, whose voice shapes the rituals and beliefs of the Sisterhood. He is never seen by the unworthy, his presence mediated through the chancel screen and the Superior Sister. "He" represents the patriarchal, authoritarian order that underpins the House, his words both sacred and empty. In the novel's climax, he is revealed as a perpetrator of abuse, his divinity exposed as a lie. "He" is both a symbol and a person, the embodiment of the violence and hypocrisy at the heart of the Sisterhood.

Helena

Helena is the narrator's first protector and perhaps her first love, a woman marked by compassion and defiance. Her willingness to save the narrator, to share forbidden words and touch, marks her as a heretic. Betrayed by the narrator, Helena is buried alive, her name erased from memory. She haunts the narrator's dreams and writings, a symbol of both the cost of love and the possibility of redemption. Helena's fate is a warning and a source of hope, a reminder that even in a world built on violence, compassion can survive.

Lourdes

Lourdes is the narrator's chief rival among the unworthy, a master of punishments and a favorite of the Superior Sister. Her intelligence and cruelty make her both feared and admired. Lourdes's jealousy of Lucía leads her to violence and ultimately to her own death at the hands of the Superior Sister. Her fate is both a warning and a tragedy, a reminder of the House's capacity to consume its own. Lourdes's complexity lies in her vulnerability: beneath her cruelty is a longing for acceptance and love, a fear of being unworthy.

Circe

Circe is the narrator's closest companion before the House, a wild cat named after the mythic sorceress. Together they survive the ravaged world, forming a pack of two. Circe's death at the hands of men in the metallic woods is a defining trauma for the narrator, shaping her fear, her capacity for love, and her need to write. Circe is both a literal and symbolic figure, representing the possibility of connection in a world of violence, and the inevitability of loss.

María de las Soledades

María de las Soledades is a fellow unworthy, marked by physical and psychological suffering. Her refusal to conform, her longing for another name, and her eventual silence make her a target for punishment. Her death in the Tower of Silence is both a personal tragedy and a symbol of the House's capacity for cruelty. María de las Soledades's fate is a warning to others, a reminder of the cost of difference and the power of solidarity.

The Servants

The servants are the lowest caste in the House, marked by physical signs of contamination and denied even the dignity of names. They perform the dirtiest tasks, absorb the House's rage, and are both feared and despised by the unworthy. Their suffering is a constant reminder of the world's collapse and the fragility of purity. Occasionally, a servant's small act of resistance or kindness disrupts the order, but their fate is always precarious.

The Chosen (Minor Saints, Full Auras, Diaphanous Spirits)

The Chosen are the House's most sacred caste, marked by physical mutilation (sewn eyes, cut tongues, perforated eardrums) and ritual purity. They are both revered and pitied, their suffering a spectacle for the unworthy. The Chosen's voices, visions, and silences are interpreted as divine messages, but their humanity is erased. Their deaths are both tragedy and celebration, their bodies exposed to the elements as a final act of purification.

Plot Devices

Ritual and Hierarchy

The novel's world is structured by elaborate rituals—ceremonies of blood, song, and sacrifice—that both create and enforce a rigid hierarchy. These rituals are designed to erase individuality, enforce submission, and justify violence as sacred duty. The hierarchy of the House (Enlightened, Chosen, unworthy, servants) is maintained through physical mutilation, deprivation, and the constant threat of punishment. Rituals are both a means of survival and a mechanism of control, shaping every aspect of life and thought.

Unreliable Narration and Fragmented Memory

The narrator's account is marked by gaps, contradictions, and moments of uncertainty. Her memory is fragmented by trauma, her writing both confession and invention. The truth is always shifting, always containing a lie at its core. This narrative instability mirrors the instability of the House's world, where reality is shaped by rumor, ritual, and the need to survive. The use of secret writing as both plot device and symbol underscores the power of storytelling to resist erasure.

Nature as Miracle and Threat

The appearance of fireflies, wasps, and bees in a dying world is experienced as miracle, threat, and omen. Nature responds to the characters' actions, blurring the line between the miraculous and the monstrous. The scarcity of uncontaminated food, the threat of haze and acid rain, and the rituals of purification all reflect the world's ecological collapse. Nature is both a source of hope (the possibility of renewal) and a reminder of what has been lost.

Forbidden Love and Solidarity

The central relationship between the narrator and Lucía is both a source of hope and a constant danger. Their love is forbidden by the House's rules, but it becomes a form of resistance, a way to imagine another world. The memory of Helena and Circe, the solidarity among the unworthy, and the small acts of kindness among the servants all point to the possibility of connection in a world built on violence. Love is both a risk and a necessity.

The Book of the Night

The narrator's secret writing is both a plot device and a symbol: a way to remember, to bear witness, and to imagine a future beyond the House. The act of writing is dangerous, forbidden, and ultimately redemptive. The "book of the night" becomes a testament to survival, love, and the possibility of change. Its fate—hidden in the hollow of a tree, awaiting discovery—mirrors the novel's hope that even in a world built on forgetting, memory and resistance can endure.

Analysis

The Unworthy is a haunting exploration of life in a post-apocalyptic matriarchal theocracy, where ritualized violence, ecological collapse, and patriarchal abuse intersect. Bazterrica's narrative is both intimate and allegorical, using the claustrophobic world of the Sacred Sisterhood to examine the mechanisms of power, the cost of survival, and the possibility of resistance. The novel's fragmented structure, unreliable narration, and lush, brutal imagery evoke the psychological disintegration wrought by trauma and isolation. At its core, The Unworthy is a story about the search for meaning and connection in a world designed to erase both. The forbidden love between the narrator and Lucía becomes a beacon of hope, a reminder that even in the darkest circumstances, solidarity and desire can create moments of beauty and rebellion. The novel's ending—an act of sacrifice, escape, and the preservation of memory—suggests that while systems of oppression may endure, the human capacity for love, storytelling, and resistance is equally persistent. In a world without mirrors or windows, the act of writing becomes both a weapon and a refuge, a way to ensure that the unworthy are not forgotten.

Last updated:

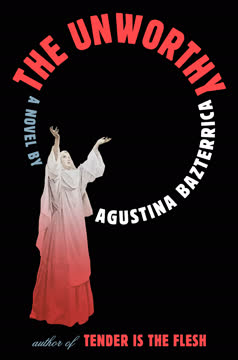

Review Summary

The Unworthy is a disturbing dystopian novel set in a post-apocalyptic world ravaged by climate change. It follows women in a cruel religious cult, exploring themes of power, misogyny, and survival. Readers praised Bazterrica's vivid, poetic writing and the book's ability to unsettle, though some found the ending unsatisfying. Many compared it to her previous work, Tender is the Flesh, with mixed opinions on which was better. The short novel's graphic violence and oppressive atmosphere left a lasting impact on most readers.