Key Takeaways

1. Spices: Nature's Potent Flavor Chemicals.

Spice flavors are chemicals produced by plants, often for defence.

Plant defense mechanisms. Spices are essentially concentrated packets of chemicals that plants developed for survival. These compounds serve various roles in nature, such as repelling pests, attracting pollinators, or protecting against infections. By happy coincidence, many of these defensive chemicals have aromas and tastes that humans find appealing.

Beyond leafy herbs. Unlike herbs, which come from leafy parts and are often used fresh, spices typically derive from dried seeds, fruits, roots, stems, flowers, or bark. This structural difference often means spices contain a higher concentration of flavor compounds, making them more potent and suitable for adding deep, background flavor rather than fresh notes. Examples include:

- Seeds (cumin, cardamom)

- Fruits (allspice, chili)

- Roots (turmeric, ginger)

- Bark (cinnamon, cassia)

Historical and culinary value. Throughout history, spices have been valued not just for cooking, but also for medicinal properties and in religious ceremonies. Science now reveals that the once-mystical powers of these plant parts are directly linked to the specific flavor compounds they contain, which interact with our senses and even our physiology.

2. Flavor Compounds: The Molecular Basis of Taste.

Flavor compounds are the tiny molecules that give each spice its unique flavor.

Aromas and tastes. When we experience the flavor of a spice, we are sensing specific molecules. These molecules travel up the throat to the nose (aroma) or interact directly with taste receptors on the tongue (taste). Understanding these compounds is crucial for unlocking creativity in the kitchen.

Oil vs. water solubility. Most flavor compounds in spices are oil-soluble, meaning they dissolve and disperse best in fats or alcohol, not water. They are often stored in oil glands within the plant structure and are released when the plant is damaged or heated. This solubility affects how flavors are best extracted and distributed in cooking.

Beyond traditional taste. Some compounds in spices don't fit the traditional definition of flavor (aroma sensed by the nose). These "tastants" directly stimulate nerves on the tongue, causing sensations like:

- Sweetness (sugars)

- Sourness (acids)

- Bitterness

- Numbness

- Coldness

- Spicy heat (pungent compounds)

3. Spice Groupings: A Scientific Framework for Understanding Flavors.

Using features shared by compounds, I have organized spices into 12 flavor groups.

Organizing complexity. With hundreds of flavor compounds across different spices, understanding their interactions can seem daunting. By grouping spices based on their dominant flavor compounds and shared characteristics, we create a simpler framework for predicting how they might pair. This moves beyond trial-and-error or tradition alone.

Shared characteristics. Each flavor group represents spices that share key chemical similarities, leading to overlapping taste profiles or sensory effects. For example, spices high in phenols often have warming, sweet, or medicinal notes, while those high in certain terpenes might be fragrant, earthy, or penetrating.

Predicting harmony. Spices within the same group often blend well due to their shared chemical foundation. However, the real power comes from understanding how spices from different groups can connect through minor shared compounds, creating complex and harmonious blends that might not be obvious from their dominant flavors alone.

4. The Periodic Table of Spices: Your Culinary Flavor Map.

Taking inspiration from the scientific world, I have devised this Periodic Table of Spices as a starting point for a new way of thinking about spices.

Visualizing flavor relationships. Just as the chemical periodic table organizes elements by their properties, the Periodic Table of Spices organizes spices by their dominant flavor groups. This visual tool provides a quick reference for identifying spices with similar profiles or potential connections.

Beyond traditional categories. The table moves beyond simple "sweet" or "savory" labels, categorizing spices based on the specific chemistry that drives their taste. This allows for more nuanced understanding and creative pairing possibilities. The 12 groups include:

- Sweet Warming Phenols

- Warming Terpenes

- Fragrant Terpenes

- Earthy Terpenes

- Penetrating Terpenes

- Citrus Terpenes

- Sweet-Sour Acids

- Fruity Aldehydes

- Toasty Pyrazines

- Sulfurous Compounds

- Pungent Compounds

- Unique Compounds

A tool for exploration. The table serves as a starting point. By identifying the dominant group of a spice you want to use, you can then explore other spices within that group or look for connections to spices in other groups based on shared minor compounds, as detailed in individual spice profiles.

5. Science of Blending: Pairing Spices by Shared Compounds.

Complexity increases with each extra spice, and so will pleasure— research shows that the greater the range of flavors and mouth sensations in a dish, the tastier it will be.

The principle of shared compounds. The most reliable way to create harmonious spice blends is by pairing spices that share one or more flavor compounds, even if those compounds are minor in one of the spices. These shared molecules act as bridges, linking different flavor profiles together.

Building complexity. Start by choosing one or two primary spices from a flavor group that defines the main taste you want (e.g., Citrus Terpenes for a zesty dish). Then, add complexity by introducing spices from other flavor groups that share compounds with your primary choices. This layering of shared molecules creates a more rounded and interesting flavor profile.

Avoiding clashes. Spices with no shared flavor compounds are more likely to clash, resulting in discordant tastes. By consulting the blending science for each spice, you can identify potential molecular connections and build blends that are scientifically likely to be delicious and exciting to the palate.

6. Unlock Flavor: Techniques for Maximizing Spice Potential.

The vast majority of flavor compounds in spices are oil- rather than water-soluble and are stored within bubbles of oil.

Releasing trapped flavors. Spice flavors are often locked within the plant's structure, particularly in oil glands. To release these compounds, the spice needs to be damaged (bruised, ground) and often heated. Different techniques are needed depending on the spice and its compounds.

The role of fat and alcohol. Since most flavor compounds are oil-soluble, cooking with fats (like oil, butter, or coconut milk) or alcohol is highly effective for extracting and distributing flavor throughout a dish. Water alone is less efficient for many spices.

Heat and time. Applying heat helps flavor compounds evaporate and spread, but excessive heat can also cause delicate compounds to degrade or new, undesirable bitter flavors to form (e.g., scorching paprika). Slow cooking allows time for flavors to diffuse from tougher structures (like bark or whole seeds), while quick cooking requires pre-grinding or using more volatile spices.

7. World of Spice: Tradition and Science in Regional Palettes.

Centuries of cooking experience are the bedrock of every country’s food heritage...

Traditional wisdom. Regional spice palettes are not random; they are the culmination of centuries of culinary experience, trade, and adaptation to local ingredients and climates. Cooks discovered through trial and error which spices grew locally, which were available through trade, and how they best complemented regional dishes.

Trade routes shaped cuisine. Ancient trade routes like the Silk Road and Spice Route facilitated the exchange of spices across continents, profoundly influencing regional cuisines. Spices native to Asia became staples in the Middle East and Africa, while New World spices like chili and vanilla revolutionized cooking in Europe and Asia.

Science validates tradition. Modern spice science often validates the wisdom embedded in traditional regional blends. For example, the ubiquitous pairing of cumin and coriander in many cuisines works beautifully because they share flavor compounds like cymene and pinene, creating a scientifically harmonious blend. Exploring regional palettes offers a wealth of proven pairing ideas to build upon.

8. Sweet Warming Phenols: Comforting and Aromatic Spice Family.

The warming, sweetly aromatic spices in this group owe their main flavor to compounds in the phenol family.

Defining characteristics. This group includes spices like cinnamon, cassia, clove, star anise, anise, licorice, mahleb, allspice, and vanilla. They are characterized by flavors that are often perceived as sweet, warming, aromatic, and sometimes medicinal or aniseed-like. Key compounds include eugenol (clove, allspice), cinnamaldehyde (cinnamon, cassia), and anethole (anise, star anise, fennel).

Culinary applications. These spices are versatile, used in both sweet and savory dishes. Their warming nature makes them popular in cold-weather cooking, while their sweetness enhances desserts and can balance rich or sour flavors in savory meals.

- Cinnamon/Cassia: Baking, stews, curries.

- Clove/Allspice: Pickling, meat dishes, mulled drinks.

- Anise/Star Anise/Fennel: Baked goods, liqueurs, broths, fish.

- Licorice/Mahleb: Baking, sweets, some meat dishes.

- Vanilla: Desserts, seafood, sauces.

Blending within the group. Spices within this group often blend well due to shared phenolic compounds. For instance, clove and allspice both contain eugenol, creating a natural harmony. Blending them with spices from other groups can be achieved by finding connections through minor compounds like terpenes (e.g., linalool in allspice and coriander).

9. Pungent Compounds: The Science of Spicy Heat and Sensation.

These sometimes alarmingly hot spices share compounds that are not flavors at all, but chemicals that create an illusion of burning...

Heat is a sensation, not a flavor. Spices in this group, such as chili, black pepper, Sichuan pepper, and grains of paradise, contain compounds that activate pain or temperature receptors in the mouth, creating sensations of heat, tingling, or numbness rather than traditional aroma or taste. Key compounds include capsaicin (chili), piperine (black pepper), and sanshools (Sichuan pepper).

Varying effects. Different pungent compounds create distinct sensations:

- Capsaicin (Chili): Burning heat, often lingering.

- Piperine (Black Pepper): Warming, slightly woody heat.

- Sanshools (Sichuan Pepper): Numbing, tingling, buzzing sensation.

- Paradol (Grains of Paradise): Peppery, pungent warmth.

Blending for complex heat. Combining spices from this group allows for layering different types of heat and sensation. Pairing them with spices from other groups can be done by finding connections through shared aromatic compounds like terpenes (e.g., limonene in chili and coriander) or phenols, which can balance or enhance the heat.

10. Unique Compounds: Discovering Distinctive Spice Characters.

Some compounds are unique in the world of spices or do not fit in other groups.

Beyond the common categories. While many spices fit neatly into groups based on dominant shared compounds, some possess signature molecules that are rare or unique. These spices bring truly distinctive characters to dishes. Examples include saffron, turmeric, fenugreek, ajwain, celery seed, and poppy seed.

Distinctive profiles:

- Saffron: Bitter, hay-like, metallic (Picrocrocin, Safranal).

- Turmeric: Earthy, musky, slightly bitter (Turmerone).

- Fenugreek: Bittersweet, maple syrup, musty (Sotolon).

- Ajwain: Bitter, herbaceous, thymelike (Thymol).

- Celery Seed: Bitter, savory, grassy (Phthalides).

- Poppy Seed: Nutty, mild, green (2-Pentylfuran).

Pairing unique spices. Blending these spices requires understanding their specific unique compounds and finding other spices that share minor aromatic notes or provide complementary tastes (sweet, sour, bitter) or sensations (heat, coolness) to balance their strong personalities. Traditional regional uses often provide excellent starting points for pairing these distinctive flavors.

Last updated:

FAQ

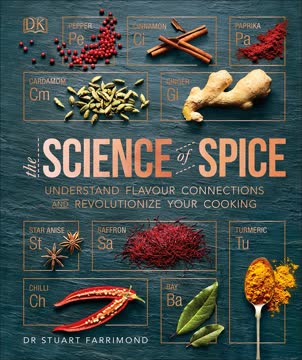

What’s [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond about?

- Comprehensive spice science: The book explores the chemistry, history, and culinary uses of spices, explaining their flavor compounds and how to blend them for maximum impact.

- Global culinary journey: It covers spice trade routes, regional spice palettes, and the influence of spices on cuisines worldwide.

- Practical applications: Readers get detailed spice profiles, recipes, and a unique Periodic Table of Spices to guide creative cooking.

- Scientific and cultural insights: The book combines food science with cultural stories, showing how spices have shaped global cuisines.

Why should I read [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond?

- Unlock flavor potential: Learn science-based methods to release and enhance spice flavors, moving beyond guesswork in the kitchen.

- Blend with confidence: The book demystifies spice blending, making it accessible for both beginners and experienced cooks.

- Global inspiration: Discover new flavor combinations and traditional blends from around the world, broadening your culinary repertoire.

- Practical and empowering: It provides actionable advice and scientific principles to help you experiment and innovate with spices.

What are the key takeaways from [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond?

- Flavor compound understanding: Spices are grouped by dominant flavor compounds, which determine their taste and how they interact in blends.

- Blending made simple: The Periodic Table of Spices and blending science help readers create harmonious and balanced spice mixes.

- Cooking techniques matter: Methods like toasting, grinding, and timing of spice addition are crucial for maximizing flavor.

- Cultural context: The book highlights how history, geography, and trade have shaped regional spice traditions and blends.

How does [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond explain the science behind spice flavors?

- Flavor compound groups: Spices contain compounds like phenols, terpenes, aldehydes, acids, and sulfurous or pungent chemicals, each contributing unique flavors.

- Chemical roles in plants: These compounds evolved for plant defense or reproduction, but humans use them for their aromatic and flavorful properties.

- Flavor release mechanisms: Grinding, bruising, or heating spices releases volatile, oil-soluble compounds, with stability affected by cooking methods.

- Flavor mapping: The book’s Periodic Table of Spices visually categorizes spices by their dominant compounds for easy understanding.

What is the "Periodic Table of Spices" in [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond?

- Visual flavor mapping: The Periodic Table of Spices categorizes spices by their dominant flavor compounds and groups.

- Blending tool: It helps identify which spices share similar chemical profiles and can be blended harmoniously.

- Practical guidance: Cooks can use it to create balanced spice mixes and understand complementary or contrasting flavors.

- Educational resource: It demystifies the science of spice pairing, making blending more accessible.

How does [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond advise creating spice blends and pairings?

- Start with flavor groups: Select desired flavor profiles using the Periodic Table of Spices, such as spicy, earthy, or citrusy.

- Check for shared compounds: Pair spices with similar or complementary flavor compounds for harmonious blends.

- Build complexity: Add spices from additional groups that share compounds with your base spices to enrich the blend.

- Adjust for cooking method: Consider how spices behave in oil, water, or heat, and adjust blend composition accordingly.

What are the main flavor compound groups in [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond, and what are their characteristics?

- Sweet Warming Phenols: Spices like clove and cinnamon, with sweet, aromatic, and warming flavors from phenol compounds.

- Warming Terpenes: Spices such as cumin and nutmeg, offering woody, peppery, and warm notes.

- Sulfurous Compounds: Garlic and mustard provide pungent, oniony, and meaty flavors due to sulfur compounds.

- Citrus Terpenes: Lemongrass and lemon myrtle deliver tangy, refreshing, lemony flavors from citrus-scented terpenes.

- Pungent Compounds: Chili and black pepper create spicy heat and tingling sensations by activating pain receptors.

How does [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond explain the process of releasing spice flavors in cooking?

- Grinding and toasting: Grinding breaks open flavor capsules, while toasting in a dry pan releases oils and creates new flavor compounds.

- Cooking medium matters: Most flavor compounds dissolve better in fats and alcohol, so cooking spices in oil or butter maximizes extraction.

- Timing and temperature: Adding spices early allows flavors to infuse, but delicate compounds may require late addition to prevent loss.

- Avoid overheating: Overcooking spices can cause bitterness or aroma loss, so careful temperature control is important.

How does [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond describe the role of spices in global cuisines?

- Historical trade influence: The book traces ancient spice trade routes and their impact on regional cuisines.

- Regional spice palettes: It details characteristic spices and blends from the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, the Americas, and Europe.

- Cultural fusion: Many cuisines reflect centuries of exchange, colonization, and migration, resulting in diverse spice uses and signature blends.

- Local adaptations: The book highlights how local ingredients and traditions shape unique spice applications.

What practical advice does [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond give for buying, storing, and using spices?

- Buy whole, grind fresh: Whole spices retain flavor longer; grind just before use for maximum aroma and potency.

- Use proper cooking methods: Toast, fry, or infuse spices as appropriate to release their best flavors.

- Balance flavors: Combine spices with shared compounds for harmony, and balance pungency, sweetness, bitterness, and acidity.

- Store correctly: Keep spices in airtight containers away from light, heat, and moisture to preserve their shelf life.

What are some classic spice blends and recipes featured in [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond?

- Classic blends: Includes Arabic Baharat, Garam Masala, Za’atar, and Harissa, each with unique regional profiles.

- Diverse recipes: Features dishes like Chinese Steamed Salmon with Chili and Star Anise, Chicken and Eggplant Biryani, and West African Peanut Curry.

- Spice-focused cooking: Each recipe highlights specific spice blends or profiles, teaching effective spice use.

- Flavor release tips: Recipes incorporate advice on when and how to add spices for maximum aroma and taste.

What are the best quotes from [Science of Spice] by Stuart Farrimond and what do they mean?

- Empowering cooks: “This book serves up easy-to-follow, science-based principles that will transform the way you use spices.” — Encourages readers to innovate confidently with spices.

- Value of complexity: “Complexity increases with each extra spice, and so will pleasure—research shows that the greater the range of flavors and mouth sensations in a dish, the tastier it will be.” — Highlights the benefits of layering flavors.

- Creative freedom: “No one should be shackled by recipes from chefs, internet ‘gurus,’ or family tradition.” — Advocates for experimentation and personal expression in spice use.

- Scientific insights: Quotes like “Cineole’s cooling effect stimulates cold receptor TRPM8…” and “Citral is unstable and breaks down over time…” explain the sensory science behind spice flavors.

Review Summary

The Science of Spice receives mostly positive reviews, with readers praising its comprehensive information, beautiful design, and scientific approach to spices. Many find it useful for expanding their culinary knowledge and improving their cooking. Some criticize its oversimplification of certain cuisines and cultural insensitivity. The book's layout can be challenging on e-readers. Overall, readers appreciate the in-depth exploration of spice history, chemistry, and usage, though some find it too technical or basic depending on their existing knowledge.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.