Plot Summary

Awakening in Captivity

Yolanda and Verla, strangers, wake in a remote, locked room, disoriented and stripped of their identities. Both are dressed in coarse, outdated uniforms, their hair later shorn, and their personal belongings gone. The environment is harsh, the air thick with the calls of unfamiliar birds, and the sense of isolation is immediate. As they grope for understanding, fear and confusion mingle with the remnants of sedation. Their first contact is wordless, a shared grip of hands as male guards enter, signaling the beginning of their ordeal. The realization dawns: they have been abducted, and their captors are both indifferent and cruel. The women's pasts—scandals, betrayals, and public shaming—linger in their minds, but now survival is all that matters.

Shaved Heads, Shattered Selves

The women are led, one by one, to have their heads shaved, a ritual of control and erasure. The act is both physically and psychologically violent, stripping away their individuality and dignity. The guards, Boncer and Teddy, alternate between bored cruelty and casual misogyny, reinforcing the women's powerlessness. The group of captives grows: ten women, all with stories of public disgrace, are forced into identical uniforms and subjected to arbitrary rules. The environment is barren, the buildings dilapidated, and the sense of being watched and judged is constant. The women's identities blur, their pasts reduced to tabloid headlines and slurs. The first day is a lesson in submission, and the seeds of resistance and solidarity are sown in shared suffering.

The March and the Fence

The women are chained together and marched under the broiling sun, their feet blistering in ill-fitting boots. Boncer, wielding a baton, enforces discipline with violence. The march is both a test and a demonstration: the compound is encircled by a high, electrified fence, humming with lethal energy. The message is clear—escape is impossible, and disobedience will be met with pain or death. The landscape is desolate, the sky vast and indifferent. The women's minds wander to memories of home, family, and the events that led them here. The fence is both a physical and psychological barrier, a symbol of their total isolation. The return to the compound is slow and painful, and the reality of their captivity settles in.

The Rules of Survival

The women are herded into dogbox-like cells at night, locked away from each other, forced to relieve themselves in corners. Days are spent in grueling manual labor—moving concrete, clearing land, building a road for the mysterious "Hardings." Food is scarce and revolting, water rationed, hygiene impossible. The guards' moods dictate the women's treatment, and violence is always a threat. The women form fragile alliances, sharing stories through the thin walls, but trust is rare. Each clings to hope—of rescue, of justice, of return to a life that now seems impossibly distant. The rules are arbitrary, the punishments capricious, and the only certainty is that they are utterly forgotten by the outside world.

The Dogboxes and the Bonnets

Each night, the women are locked in individual cells—dogboxes—stripped of comfort and privacy. They are forced to wear bonnets with visors, further limiting their vision and ability to communicate. The bonnets are both a tool of humiliation and a means of control, making even whispered conversation difficult. The women's bodies begin to change—hair grows back in wild tufts, skin toughens, and the line between human and animal blurs. The guards' surveillance is constant, and the threat of sexual violence hangs in the air. The women's sense of self erodes, replaced by a raw, animal will to survive. Yet, in the darkness, small acts of kindness and rebellion persist.

Labor, Hunger, and Hierarchy

As food supplies dwindle, hunger gnaws at the women's bodies and minds. Labor becomes more punishing, and the guards' tempers fray. The women are forced to scavenge, to eat whatever they can find—rabbits, weeds, even mushrooms of uncertain safety. Hierarchies emerge: some women barter for privileges, others are scapegoated or ostracized. The guards, too, are changed by deprivation, their authority undermined by fear and resentment. The women's bodies become tools and weapons—Yolanda, in particular, embraces her animality, fashioning clothing from rabbit skins and wielding traps. The line between captor and captive blurs, as everyone is reduced to the struggle for survival.

The Woman Called Nancy

Nancy, a young woman in a parody of a nurse's uniform, appears as the compound's medic. Her presence is unsettling—childlike, capricious, and ultimately powerless. She dispenses crude medical care, but her interventions are often more harmful than helpful. Nancy's own instability mirrors the breakdown of order in the compound. Her relationship with the guards is ambiguous, and her authority is undermined by her addiction to pills and her desperate need for approval. For the women, Nancy is both a potential ally and a reminder of their vulnerability. Her eventual overdose and death mark a turning point, as the women are left to care for their own sick and dying.

The Rituals of Deprivation

In the face of relentless deprivation, the women develop rituals to maintain their sanity—singing, storytelling, grooming, and the creation of a grotesque doll from scraps and hair. These acts are both a comfort and a form of resistance, asserting their humanity in the face of dehumanization. The doll, in particular, becomes a symbol of their collective suffering and resilience, absorbing their pain and rage. The women's relationships shift—alliances form and dissolve, betrayals sting, and moments of tenderness offer fleeting relief. The guards' power wanes as the women grow stronger, more resourceful, and more united in their refusal to be broken.

The Road to Nowhere

As the women complete the road for Hardings, hope flickers that their ordeal might end. But the outside world remains silent, and the guards themselves are abandoned, their authority crumbling. The arrival of a hot-air balloon, glimpsed fleetingly, is a cruel reminder of their invisibility—waved at, but not saved. The women's sense of time and self erodes further, and the compound becomes a world unto itself, governed by its own brutal logic. The boundaries between captor and captive, human and animal, blur beyond recognition. The only certainty is that no one is coming to save them.

The Power of Animality

Yolanda, in particular, embraces her animal nature, becoming a hunter, skinner, and survivor. She fashions clothing from rabbit skins, sets traps, and provides food for the group. Her transformation is both a survival strategy and a rejection of the shame imposed on her. The other women, too, adapt—some through faith, some through ritual, some through violence. The compound becomes a microcosm of a world stripped to its essentials: hunger, pain, desire, and the will to endure. The women's bodies and minds are remade by their experiences, and the possibility of escape or return to "normal" life grows ever more remote.

The Doll and the Sacrifice

The women, led by Verla and Yolanda, create a doll from scraps, hair, and rabbit skins—a totem of their suffering and a gift for Hetty, who bargains her body for privileges with Boncer. The doll absorbs their collective trauma, its body stitched with scars and secrets, a tiny dead rabbit sewn inside. Hetty's sacrifice is both a betrayal and an act of survival, and the group's complicity is a source of shame and relief. The doll becomes a symbol of what has been lost—innocence, dignity, and the hope of rescue. Its presence haunts the compound, a reminder of the price of endurance.

Hetty's Bargain

Hetty offers herself to Boncer in exchange for food, clothing, and protection, a bargain that both saves and damns her. The other women, relieved to be spared, are nonetheless complicit in her exploitation. Hetty's status shifts—she is both envied and despised, her body a site of power and vulnerability. The group's moral boundaries blur, and the logic of survival overrides solidarity. When Hetty becomes pregnant and ultimately dies at the electrified fence, her fate is both a warning and a release. The burial is communal, but the sense of guilt and loss lingers.

The Poison and the Death Cap

As Boncer's violence escalates, Verla turns to the natural world for a weapon—mushrooms, some edible, some deadly. She experiments in secret, seeking the elusive death cap. The act of poisoning becomes both a fantasy of justice and a test of agency. When the moment comes, Boncer unwittingly eats the fatal mushroom, and his slow, agonizing death is both a triumph and a horror. The women's complicity in his demise is unspoken, but the sense of liberation is tempered by the knowledge that violence begets violence. The boundaries between victim and perpetrator, justice and revenge, are irrevocably blurred.

The End of Boncer

Boncer's death is both a release and a reckoning. The women, now truly alone, must confront the reality of their situation—no guards, no rules, no hope of rescue. The power vacuum is filled by uncertainty and fear. The rituals of survival continue—cooking, cleaning, caring for the sick—but the sense of purpose is gone. The women are changed, their bodies and minds marked by what they have endured. The outside world, once a source of hope, now seems alien and unattainable. The question of what comes next hangs over them, unanswered.

The Return of Power

The power returns, and with it, the promise of rescue. A bus arrives, driven by a clean, paternal figure, bearing luxury toiletries and promises of return to the world. The women, dazed and transformed, are both drawn to and repelled by the trappings of civilization—creams, razors, perfumes. The bus is both a vehicle of escape and a new kind of prison, its destination uncertain. Yolanda refuses to board, choosing instead to disappear into the wild, fully animal, fully free. Verla, torn between hope and despair, makes her own choice, refusing the easy comforts of return.

The Bus and the Bags

The women, clutching their luxury bags, are herded onto the bus, their future uncertain. The driver's paternalism is both comforting and sinister, and the women's transformation is both celebrated and erased. The bus turns not toward home, but into the setting sun, and the realization dawns that their ordeal is not over. Verla, holding the last death cap, faces a final choice—life, death, or something beyond both. The women's laughter and chatter fill the bus, but beneath the surface, the scars of captivity remain.

Yolanda's Refusal

Yolanda, now fully animal, refuses the bus, the bags, and the promise of return. She disappears into the wild, her body clothed in skins, her mind free from the shame and violence of her past. Her refusal is both an escape and a statement—a rejection of the world that condemned her, a claim to a new kind of freedom. Verla, watching her go, feels both loss and admiration. The bond between the two women, forged in suffering, endures beyond words or rescue.

Verla's Choice

On the bus, surrounded by the trappings of civilization, Verla faces her own moment of truth. She holds the death cap, contemplates escape through death, but ultimately chooses to refuse—to refuse the narrative imposed on her, to refuse victimhood, to refuse erasure. She demands to be let off the bus, to walk her own path, uncertain but self-determined. The story ends with Verla alone on the road, the future open, the past unerasable, but the possibility of agency reclaimed.

Characters

Yolanda Kovacs

Yolanda is a young woman whose public shaming and sexual victimization have led to her imprisonment. Initially defiant and resourceful, she quickly adapts to the brutal conditions, embracing her animality as a means of survival. She becomes the group's hunter, skinner, and provider, fashioning clothing from rabbit skins and wielding traps with skill. Her relationship with Verla is complex—marked by mutual respect, occasional rivalry, and deep, unspoken solidarity. Yolanda's journey is one of reclamation: she refuses to be defined by her trauma or by the narratives imposed on her. Her ultimate refusal to return to civilization is a radical act of self-determination, a rejection of both victimhood and the world that condemned her.

Verla Learmont

Verla is a parliamentary intern whose affair with a powerful man has made her a public scapegoat. She clings to her sense of self through memory, poetry, and ritual, but the compound's brutality strips away her illusions. Verla's relationship with Yolanda is central—she admires Yolanda's strength, envies her resilience, and ultimately learns from her example. Verla's arc is one of disillusionment and awakening: she moves from hope of rescue to a recognition of her own agency. Her final refusal to accept the narrative of victimhood, and her choice to leave the bus, mark her as a survivor not just of the compound, but of the world's expectations.

Boncer

Boncer is the chief guard, a man whose power is rooted in cruelty, insecurity, and resentment. He enforces the compound's rules with arbitrary violence, relishing his control over the women. Boncer's own vulnerability is evident—he is desperate for approval, fearful of being abandoned, and ultimately undone by his own brutality. His relationship with Hetty is both exploitative and pathetic, and his death is both a triumph and a warning. Boncer represents the banality of evil, the way ordinary men become monsters in systems of unchecked power.

Teddy

Teddy is the younger, more passive guard, whose initial indifference gives way to fear and complicity. He is both attracted to and repelled by the women, and his attempts at kindness are undermined by his cowardice. Teddy's relationship with Nancy is ambiguous—he uses her, but is also used by her. As the compound's order collapses, Teddy becomes increasingly irrelevant, his authority eroded by addiction and fear. His death is anticlimactic, a footnote to the women's struggle.

Nancy

Nancy is the compound's medic, a young woman whose affect is alternately girlish and cruel. She dispenses crude medical care, but her interventions are often more harmful than helpful. Nancy's addiction to pills and her desperate need for approval make her both pitiable and dangerous. Her death by overdose is both a release and a loss, marking the end of any pretense of care or order in the compound.

Hetty

Hetty is a young woman whose public disgrace is compounded by her willingness to bargain her body for survival. She becomes Boncer's "pet," trading sex for food and privileges, and is both envied and despised by the others. Hetty's creation of the doll, her pregnancy, and her ultimate death at the fence are all acts of both agency and victimhood. She embodies the ways in which women are forced to navigate systems of exploitation, and her fate is both a warning and a release.

Isobel (Izzy)

Izzy is a former airline worker whose scandal has left her vulnerable and adrift. She clings to memories of comfort—her boots, her hair, her old life—but adapts to the compound's realities with surprising resilience. Izzy's relationships with the other women are marked by both solidarity and competition, and her moments of kindness are often undercut by self-preservation. She represents the ordinary woman caught in extraordinary circumstances, forced to become both harder and more resourceful.

Lydia

Lydia is a cruise ship worker whose scandal has made her a target of public scorn. She is skeptical, sarcastic, and often abrasive, but her toughness masks a deep vulnerability. Lydia's alliances shift, and her survival is often at the expense of others. She is both a victim and a perpetrator, complicit in the group's betrayals and redemptions.

Joy

Joy is a former reality TV contestant whose abuse and public humiliation have left her nearly mute. Her voice, when it emerges, is powerful and transformative—a reminder of what has been lost and what endures. Joy's relationships with Lydia and Izzy are marked by tenderness and mutual care, and her eventual act of violence is both shocking and redemptive.

Barbs

Barbs is a former athlete whose outspokenness has led to her downfall. She is physically strong, often taking the lead in labor and confrontation, but her emotional wounds run deep. Barbs's longing for comfort, her attachment to rituals, and her moments of kindness make her both a leader and a source of solace for the group.

Plot Devices

Dystopian Microcosm and Allegory

The novel's central device is the isolated compound, a place where women are punished for their sexuality, their outspokenness, or simply for being inconvenient. The setting is both literal and allegorical—a stand-in for the ways society disciplines and erases women who transgress. The electrified fence, the dogboxes, the bonnets, and the rituals of deprivation all serve to strip the women of identity and agency, reducing them to bodies, to animals, to objects of control. The narrative structure is cyclical and claustrophobic, mirroring the women's entrapment and the seeming impossibility of escape.

Foreshadowing and Symbolism

The novel is rich in symbolism: the shaving of heads, the creation of the doll, the hunting and skinning of rabbits, the recurring presence of birds and kangaroos. These motifs foreshadow the women's transformation, their loss of humanity, and their eventual reclamation of agency. The natural world is both a source of danger and a site of resistance—mushrooms become both food and poison, animals both prey and kin. The fence is both a literal barrier and a symbol of the boundaries imposed by society.

Shifting Power Dynamics

The novel's structure traces the rise and fall of power—first in the hands of the guards, then in the hands of the women. As the outside world abandons the compound, the women's resourcefulness and solidarity grow, and the guards' authority crumbles. The creation of the doll, the poisoning of Boncer, and the final refusal to board the bus are all moments of inversion, where the women seize agency, however fleetingly.

Psychological Realism and Interior Monologue

The narrative is driven by the interior lives of Yolanda and Verla, whose memories, fantasies, and psychological struggles are rendered in vivid detail. The use of interior monologue allows for a nuanced exploration of trauma, shame, and the search for meaning. The women's relationships—with each other, with their bodies, with their pasts—are central to the novel's emotional arc.

Open-Ended Resolution

The novel's ending is deliberately ambiguous—Yolanda disappears into the wild, Verla refuses both death and the comforts of civilization, and the future is left open. This refusal to provide closure is itself a statement, a rejection of the narratives imposed on women by society, by captors, by readers. The women's survival is not triumphant, but it is theirs.

Analysis

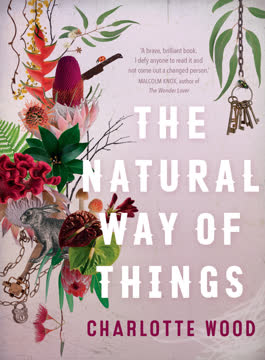

Charlotte Wood's The Natural Way of Things is a searing allegory of misogyny, complicity, and survival. Through the lens of a dystopian prison, Wood exposes the mechanisms by which society punishes and erases women who transgress—whether by speaking out, by being sexual, or simply by existing in the wrong place at the wrong time. The novel's power lies in its unflinching portrayal of dehumanization and its refusal to offer easy redemption. The women's suffering is both individual and collective, their bodies sites of both violence and resistance. The transformation of Yolanda and Verla—from victims to survivors, from women to animals to something beyond—challenges the reader to reconsider the boundaries of identity, agency, and solidarity. The novel's open ending, with its refusal of both death and return, is a radical act of self-determination. In a world that demands women's silence, compliance, and erasure, The Natural Way of Things insists on the possibility of refusal, of survival on one's own terms, and of the enduring power of sisterhood.

Last updated:

Review Summary

The Natural Way of Things by Charlotte Wood polarizes readers with its brutal depiction of ten women imprisoned in the Australian outback following sex scandals. Reviews range from five stars praising its feminist themes, visceral prose, and haunting exploration of misogyny, to one star criticizing its unrealistic premise and unsatisfying ending. Many compare it to The Handmaid's Tale and Lord of the Flies. Readers appreciate Wood's beautiful, descriptive writing but struggle with graphic violence, unanswered questions, and lack of character development. The ambiguous ending frustrates many, though some find it appropriately haunting for this dystopian critique of victim-blaming.