Key Takeaways

1. Awakening to the Feminine Wound

For girls there is always a moment when the earnest, endearing assumption of equality is lost, and writing about it in my journal thirty years later made me want to take those two eight year olds into my arms—myself and Ann, both.

The initial jolt. The author's journey began with a profound awakening, triggered by a dream of birthing herself and a pivotal incident where she witnessed her daughter's subordinate posture being mocked by men. This moment shattered her complacency, revealing a deep-seated "feminine wound" – an internalized sense of inferiority and limitation due to patriarchal conditioning in culture, church, and family. She realized she had been "asleep" to the subtle ways women are devalued.

Unconscious acceptance. For years, the author, like many women, had unconsciously accepted societal and religious narratives that positioned women as secondary. She had been a "woman in Deep Sleep," oblivious to the psychological and spiritual impact of being excluded from positions of power, silenced by biblical interpretations, and having God represented exclusively as male. This realization was painful, forcing her to confront truths she had long avoided.

Symptoms of disconnection. When cut off from the "feminine soul" – a woman's inner repository of the Divine Feminine, her natural instinct, and guiding wisdom – symptoms inevitably emerge. The author experienced self-doubt, a tendency to silence her true self, perfectionism, passivity, and a fear of conflict. These were not personal failings but manifestations of a collective wound, urging her to delve deeper into her feminine nature.

2. Dismantling Patriarchal Daughterhood

By blindly following the script, we forfeit the power to shape our own lives and identities.

Unnaming the self. The author realized that much of her life was lived as a "daughter" – internally dependent, accepting identities and directions projected onto her by the "cultural father." She identified various "faces of daughterhood" that were adaptations to the feminine wound, such as the "Gracious Lady," the "Church Handmaid," the "Secondary Partner," the "Many-Breasted Mother," the "Favored Daughter," and the "Silent Woman." These roles, though seemingly independent, were often rooted in a need to please and gain validation from male authority.

Cultural blueprints. Women are often handed "scripts" for womanhood, culturally defined roles that dictate how they should live, think, and behave. The author reflected on how her life had been "painted into existence" by church, culture, and male attitudes, rather than being self-conceived. This blind adherence to pre-written narratives leads to a forfeiture of personal power and authentic self-expression.

Internalized oppression. The author recognized her own complicity in upholding patriarchal systems, understanding that women often condition their daughters to serve male primacy. This phase involved confronting her own "daughterhood" and the internalized notions of a culture that put men at the center. It was a process of "unnaming" herself from these imposed identities to reclaim her true self.

3. Initiation Through the Labyrinth of Self

Death of the old form and new life or birth are fundamental to initiations.

The Great Transition. After awakening, the author entered a phase of "initiation," a sacred disintegration involving death and rebirth. This meant letting go of old forms, identities, and attachments to the patriarchal world that no longer served her. The "unexplored gorge" symbolized this new, mysterious terrain, requiring a descent into the depths of herself to mine new treasures.

The Ariadne myth. The myth of Ariadne became a guiding narrative for this phase. Ariadne, a princess in her father's kingdom, represents the "good daughter" of patriarchy. Her encounter with Theseus, who comes to slay the Minotaur in the labyrinth, symbolizes the emergence of a liberating energy within a woman. The labyrinth itself represents the "Great Womb" of death and rebirth, where a woman sheds old identities and confronts her "Minotaur."

Slaying the Minotaur. The Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull monster in the labyrinth, symbolizes negative, internalized patriarchal power – the "bullish, bullying, bulldozing force" within a woman's psyche. This "negative animus" manifests as self-doubt, belittling inner voices, and pressures to conform. The author's dream of growing antlers and tossing the "Bishop" (her internalized patriarchal voice) across the room symbolized her mobilization to battle and depotentiate this inner monster, a crucial step in freeing herself from its oppressive power.

4. Opening to the Divine Feminine

When we truly grasp for the first time that the symbol of woman can be a vessel of the sacred, that it too can be an image of the Divine, our lives will begin to pivot.

The need for feminine imagery. The author realized that the exclusive male imagery of God in Western tradition created an imbalance in consciousness, diminishing women's wholeness and legitimizing patriarchal power. If God is genderless, as theologians claim, then using only male forms is idolatrous and perpetuates the belief that "male is God." Recovering the Divine Feminine is essential for affirming women's worth and challenging societal imbalances.

"Herself" as the Divine. The author's dream revealed the name "Herself" for the Divine Feminine, signifying an inner experience of God as powerfully and vividly female. This realization moved beyond intellectual understanding to a deep, embodied knowing. She sought to recover external images and symbols that pointed to this presence, both in ancient Goddess history and within the Christian tradition.

Sophia and the Gnostic roots. Her search uncovered "Sophia" (Wisdom) in the Old Testament, personified as a woman coexistent with God before creation, and even identified with Christ in early Christian texts. She also explored Gnostic gospels, which depicted God as a dyad of masculine and feminine elements and referred to the Holy Spirit as female. These discoveries revealed a suppressed history of the Divine Feminine within Christianity, suggesting that her recovery is a fulfillment of its original potential.

5. Cultivating a Feminist Spiritual Consciousness

I knew that this quilt was itself, the Holy Thing, the manifestation of the Divine One.

Mystical oneness. Grounding in Divine Feminine imagery led to a new "feminine spiritual consciousness." This consciousness is characterized by "we-consciousness," a profound sense of mystical oneness and interconnection with all creation. It's the realization that everything—humans, nature, animals—is part of a vast, divine, and communitarian "quilt," challenging the illusion of separateness fostered by patriarchal hierarchies.

Resacralizing earth and body. This consciousness also involves the "resacralization of nature," recognizing the innate holiness of the earth, body, and matter as manifestations of the Divine. Unlike patriarchal spirituality's emphasis on transcendence and flight from the earthly, Divine Feminine consciousness embraces immanence—divinity present here and now, in every natural, ordinary, and sensual moment. This shift challenges the historical devaluation of women's bodies and the exploitation of the earth.

Liberation and justice. The third aspect is a consciousness of liberation, a passionate struggle for women's dignity, value, and power. This "still I rise" energy, born from recognizing the suffering and injustice inflicted upon women throughout history, transforms into a force for compassion and justice. It compels women to challenge patriarchal structures and work towards a world where all are included and valued, echoing the liberating vision of Mary of Nazareth.

6. Healing Through Female Solidarity and Deep Being

All sorrows can be borne if we put them in a story or tell a story about them.

Creating refuge. Healing the feminine wound requires creating a "refuge," a safe, sacred space for retreat and restoration. The author's dream of a "huge-lapped, marble statue of a seated woman" that turned to warm flesh when she climbed into it symbolized this need for a feminine embrace to heal her "stigmata." This refuge is found both internally and externally.

Communal weaving. Female solidarity, or "sisterhood," is a powerful healing force. The ritual of weaving a communal basket with other women symbolized braiding lives and stories together, creating a "woman-made container" of support. Sharing personal stories of fear, struggle, and transformation, and having them witnessed and validated by other women, fosters healing and a sense of not being alone. This "hearing one another into speech" allows women to see themselves more clearly and embrace their own experiences.

Deep Being. Healing also comes through "Deep Being," a practice of mindful meditation and unconditional presence with oneself. This involves bringing heart, mind, body, and soul into focus, observing thoughts and feelings without judgment, and tenderly holding one's "wounded child." Practices like Jungian analysis, mindfulness, and connecting with nature (earth, water, wind, fire) provide the space to strip away old layers, find the "grain beneath the bark," and mend fragmented parts of the self.

7. Transfiguring Anger into Creative Outrage

Rage implies an internalized emotion, a tempest within. Rage, or what might be called untransfigured anger, can become a calcified bitterness. What rage wants and needs is to move outward toward positive social purpose, to become a creative force or energy that changes the conditions that created it. It needs to become out-rage.

From rage to outrage. The author learned that anger, a natural response to injustice, needs to be transfigured. Untransfigured rage can lead to bitterness and depression, but when channeled outward, it becomes "outrage" – a creative force for positive social change. This involves moving beyond blame and creatively responding to patriarchal structures and wounds through writing, imagining, speaking out, and empowering other women.

The deep song of Christianity. Despite her anger at patriarchal Christianity, the author recognized a "deep song" within it – the core teachings of Jesus, mysticism, art, and the call to justice and compassion. Her liturgical dance at a monastery, a place that had once symbolized exclusion, became a "reuniting bridge," allowing her to experience the Sacred Feminine and Masculine coming together. This experience helped her to forgive, not by overlooking offense, but by releasing rage and rising to a higher love.

Forgiveness as release. Forgiveness, for the author, was a gradual process of releasing the need to retaliate and no longer dwelling on the offense. It was an act of letting go to move forward. Her ritual of leaving a bouquet of daffodils at the doors of a Baptist church symbolized making peace with her past and marking her forgiveness with a tangible act, allowing her to be released from the bitterness and move towards compassion.

8. Embracing Authentic Female Power

The true representation of power is not a big man beating a smaller man or a woman. . . . Rather, power is “the ability to take one’s place in whatever discourse is essential to action and the right to have one’s part matter.”

Cohesion of the female soul. Empowerment begins with the "cohesion of the female soul," a physical sensation of inner solidification and strength. This is the natural outcome of awakening, journeying, naming, challenging, shedding, reclaiming, grounding, and healing. It's about finding a "soul of one's own," the ability to voice it, and the courage to do so, transforming women into "hearty women who have their own ground and their own standing, sturdy as oak after the winds."

Buffalo medicine. The author's dreams of a white buffalo, a sacred and powerful Divine Feminine presence in Native American spirituality, symbolized "buffalo medicine" – resilient strength and persistence. This meant standing firm, flourishing despite attempts to limit or silence the feminine spirit. Receiving a tuft of buffalo fur became a tangible symbol of this gift, an intention to reclaim the power she had left behind in childhood.

Authentic power vs. control. Authentic female power is not about control, dominance, or mimicking patriarchal ways. It is a potent, forceful power that is also compassionate and empowering to others. It is the "ability to take one's place in whatever discourse is essential to action and the right to have one's part matter." This power allows women to act on behalf of their vision and soul, sometimes gently, sometimes fiercely, always knowing who they are.

9. Voicing the Soul and Finding Inner Authority

When I dare to be powerful—to use my strength in the service of my vision—then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid.

Mystic and prophet. The wise old woman in the author's dream gave her a mandate: "Your heart is a seed. Go, plant it in the world." This signified the need to balance inner mystical experience with outer prophetic action. Conscious women are both mystics, having inward experiences of the Divine, and prophets, calling society to truth and justice. This fusion allows them to express their transformed inner world outwardly.

Women on the loose. The Norwegian "kjerringsleppet" – "women on the loose" – became a symbol for the empowered self: women who improvise, surprise, and come uninvited, challenging exclusion and speaking their truth. This involves trusting one's own knowing, stepping out of expected roles, and daring to be a dissident presence. The author's decision to shift from inspirational writing to fiction, despite fears, was an act of "strumming her heart out" on a new lyre, embracing her "lyric Sappho" self.

The One-in-Herself Woman. Finding inner authority means becoming the "author" of one's own identity, securely anchored in one's feminine being. The concept of "virgin" as "one-in-herself" – belonging to oneself, not captured by others or patriarchy – became a powerful image. The author's ritual bath in the sea and creation of a mask symbolized reclaiming this autonomy. This inner solidity, like the "iron-jawed angels" of the suffragette movement, provides the resilience to face opposition and refuse to "half-live" one's life in fear.

10. Embodying a Spirituality of Naturalness

Your very flesh shall be a great poem, and have the richest fluency, not only in words, but in the silent lines of its lips and face and between the lashes of your eyes, and in every motion and joint of your body.

Becoming the sacred place. Empowerment culminates in "embodying Sacred Feminine experience," bringing it home to daily life, work, play, and relationships. This means becoming the "circle of trees" rather than just visiting it, dwelling so deeply in one's feminine consciousness that there is no separation between self and experience. It's about living out the truth in one's soul, convictions in one's heart, and wisdom in one's body.

Spirituality of naturalness. This embodied spirituality is "native" to women, arising from their feminine nature and flowing outward. It integrates three often-overlooked aspects into sacred experience:

- The earthly: Immersing oneself in nature, whether dancing on the shore or picking up trash, to feel connected to the earth's rhythms and beauty. This belonging fuels activism and responsiveness.

- The now: Being fully present in each moment, accepting "what is," even when painful. This deep presence allows for transformation and reveals the roots of injustice in everyday actions.

- The ordinary: Recognizing the holiness in mundane duties, family life, and simple acts. This means being authentically oneself in plain places, telling and being the truth, and understanding that change is created by living out soul experiences in common acts.

Passing on the legacy. The author's journey, culminating in embodying this natural spirituality, became a legacy for her daughter. Giving her a statue of Nike, Goddess of Victory, symbolized passing on the potential for female power and the importance of listening to one's "Deepest Self." This act of planting her heart in the world, for herself and for all daughters, affirms that women are the change the world is waiting for, weaving a "larger fabric" of immense importance and beauty.

Last updated:

Review Summary

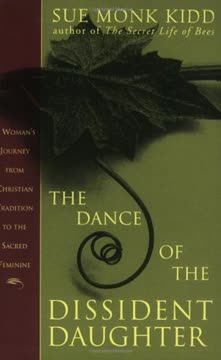

The Dance of the Dissident Daughter receives mixed reviews averaging 3.99/5 stars. Many readers praise Kidd's courageous journey from Southern Baptist tradition to embracing the Sacred Feminine, finding her story validating and transformative. Women particularly appreciated her critique of patriarchal Christianity and her exploration of feminine divinity. Critics noted her tendency to generalize personal experiences as universal, overly introspective tone, and reliance on symbols that felt contrived. Some found the second half too abstract or "woo-woo." Several reviewers valued the book despite disagreeing with her conclusions, appreciating the questions it raised about gender in religion.

Similar Books