Plot Summary

Midnight Vigil, Silent Fears

Amina, the matriarch, wakes each night to await her husband's return, her life shaped by fear, obedience, and the rituals of a household ruled by a distant, powerful man. Her world is confined to the home, haunted by superstitions and the jinn she imagines in the shadows. Married young, she has learned to find security in submission, her love for her children and husband intertwined with anxiety and resignation. The city outside is alive and mysterious, but her own existence is circumscribed by duty and the rhythms of waiting, her identity shaped by the roles imposed upon her. The night is both a companion and a threat, and her longing for connection is matched only by her fear of transgression.

Tyrant's Return, Family Order

Al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd al-Jawad returns home from his nightly revels, greeted by Amina's deference and care. To his family, he is a figure of stern discipline and religious piety, but outside, he is a man of laughter, music, and indulgence. The household is run with military precision, his word law, his presence both a comfort and a source of terror. The children—Yasin, Fahmy, Khadija, Aisha, and Kamal—navigate his moods with caution, their lives shaped by his expectations and unpredictable anger. The contrast between his public and private selves is stark, and the family's love is always tinged with fear.

Morning Rituals, Hidden Longings

The family's mornings are marked by ritual: Amina's bustling in the kitchen, the children's bickering, and Ahmad's solitary prayers. Each member plays their part, but beneath the surface, longings and frustrations simmer. Khadija and Aisha's rivalry is both comic and poignant, their futures uncertain in a world where marriage is the only escape. Yasin, the eldest son, is restless and indulgent, while Fahmy, the idealistic law student, dreams of love and revolution. Kamal, the youngest, is both innocent and precocious, absorbing the contradictions of his family and city. The house is a microcosm of Cairo, tradition and change in uneasy balance.

Daughters' Rivalry, Secret Dreams

Khadija and Aisha's relationship is defined by competition and affection. Khadija, sharp-tongued and practical, envies Aisha's beauty and ease, while Aisha, dreamy and passive, is both flattered and wounded by her sister's jibes. Their mother, Amina, tries to mediate, but her own anxieties about their futures and her lack of authority leave her powerless. Marriage proposals become the battleground for their hopes and fears, each girl measuring her worth against the other. The rituals of femininity—beauty, food, and gossip—are both a comfort and a source of pain, as the sisters wait for their lives to begin.

Forbidden Glances, Awakening Hearts

The boundaries of the home are both physical and symbolic. Aisha's secret exchange of glances with a young police officer awakens her to desire and danger, while Fahmy's rooftop encounters with Maryam, the neighbor's daughter, stir dreams of romance and rebellion. These forbidden loves are fraught with risk, as the family's honor and the father's wrath loom over every gesture. The city's streets, glimpsed through latticed windows, are a world of possibility and peril. The young people's longing for connection is matched by their fear of discovery, and the tension between tradition and change grows ever more acute.

Sons' Rebellion, Father's Shadow

Yasin and Fahmy, each in their own way, chafe against their father's control. Yasin seeks escape in sensual pleasures, haunted by the trauma of his mother's divorce and his own sense of inadequacy. Fahmy, more introspective, is drawn to politics and the ideals of the nationalist movement, his love for Maryam both a personal and political awakening. Both sons are shaped by Ahmad's contradictions—his tyranny at home, his indulgence outside—and struggle to define themselves in relation to his power. The generational conflict is both intimate and emblematic of a society in transition.

Love, Duty, and Disobedience

As marriage proposals and secret loves multiply, the family is forced to confront the limits of obedience and the costs of rebellion. Amina's longing to visit the shrine of al-Husayn leads her to defy her husband for the first time, with disastrous consequences. Yasin's reckless pursuit of pleasure brings scandal and divorce. Fahmy's political activism puts him at odds with his father and in danger from the authorities. The daughters' hopes for marriage are entangled with jealousy and disappointment. The family's unity is tested by the competing claims of love, duty, and the desire for freedom.

Marriage Proposals, Shifting Fortunes

The family's fortunes rise and fall with the arrival of marriage proposals. Aisha's engagement to a police officer is thwarted by her father's insistence on tradition, while Khadija's long-awaited proposal finally arrives, bringing relief and new anxieties. Yasin's marriage to Zaynab, the daughter of a family friend, ends in betrayal and divorce. The weddings are both celebrations and farewells, as the daughters leave home and the family's center shifts. The rituals of marriage—gifts, gossip, and feasts—mask deeper currents of longing, resentment, and change.

Husbands, Wives, and Betrayals

Marriage proves to be both a fulfillment and a source of new suffering. Yasin's inability to find satisfaction leads him to betray Zaynab with servants and strangers, his appetites unchecked by love or loyalty. Zaynab's pride and pain drive her to seek divorce, shattering the family's hopes for stability. Ahmad's own infidelities, long hidden, are mirrored in his son's failures, and the double standard of male and female desire is laid bare. The women's suffering is both personal and collective, as the costs of obedience and the limits of endurance are tested.

Mothers, Sons, and Exile

Amina's brief act of disobedience—her pilgrimage to al-Husayn—results in her exile from the home she has ruled for decades. Her absence exposes the fragility of the family's order and the depth of her children's dependence on her. The daughters struggle to manage the household, the sons are adrift, and Ahmad is forced to confront the emptiness of his authority. The reunion, when it comes, is both joyful and bittersweet, as the wounds of separation linger. The mother's love is both a source of strength and a reminder of the costs of submission.

The City in Turmoil

The city outside the family's walls is in ferment, as the nationalist movement gathers strength and the British occupation tightens its grip. Demonstrations, strikes, and violence become daily realities, and the family is drawn into the currents of history. Fahmy's involvement in the revolution brings pride and fear, as the risks of political engagement become ever more real. The family's private dramas are mirrored in the public upheaval, and the boundaries between home and street, tradition and change, are increasingly blurred.

Revolution's Fire, Family's Cost

The revolution's promise of freedom and justice is paid for in blood. Fahmy's activism leads to his death in a demonstration, a martyr to the cause of Egyptian independence. The family is shattered by grief, their private loss emblematic of the nation's suffering. Ahmad, once the unassailable patriarch, is brought low by sorrow, his authority undermined by the very forces he sought to control. The costs of change are measured in funerals and farewells, and the family's story becomes inseparable from the fate of the city and the nation.

Loss, Grief, and Endurance

The aftermath of Fahmy's death is a time of mourning and reckoning. The family must learn to live with absence, to find meaning in endurance and memory. Amina's faith and resilience are tested, Ahmad's pride is humbled, and the children are forced to grow up in a world marked by loss. The rituals of grief—prayers, visits, and stories—become a way of holding on to what has been lost and of imagining a future beyond sorrow. The family's survival is both a testament to their love and a reflection of the city's own capacity for renewal.

The Next Generation's Arrival

Even as the family mourns, new life arrives. Aisha and Khadija become mothers, their children a promise of continuity and hope. The rhythms of daily life—meals, quarrels, and celebrations—resume, altered but enduring. The family's story is both unique and universal, a chronicle of love, loss, and the search for meaning in a changing world. The city outside is still restless, but within the home, the cycle of life continues, memory and hope intertwined.

Endings, Beginnings, and Memory

As the novel closes, the family is forever changed by the events they have endured. The patriarch's authority is diminished, the children have grown and scattered, and the old certainties have been swept away by history. Yet the bonds of love, memory, and tradition persist, offering solace and the possibility of renewal. The story of the Abd al-Jawad family is both an elegy for a vanished world and a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, a portrait of a city and a family at the crossroads of past and future.

Characters

Al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd al-Jawad

The father and ruler of the Abd al-Jawad family, Ahmad is a man of contradictions: a stern, authoritarian figure at home, demanding absolute obedience and piety, yet a lover of music, wine, and women in his secret life outside. His authority is both a source of stability and oppression, shaping his children's lives and his wife's submission. Psychoanalytically, Ahmad embodies the split between public virtue and private vice, his need for control masking deep insecurities and desires. Over the course of the novel, his power is gradually undermined by the changing world and the rebellion of his children, culminating in grief and humility after Fahmy's death.

Amina

Amina is the heart of the family, her life defined by devotion, fear, and endurance. Married young, she has internalized the values of obedience and self-sacrifice, finding meaning in her roles as wife and mother. Her world is circumscribed by the home, her identity shaped by rituals and superstitions. Psychoanalytically, Amina represents the internalization of patriarchal authority, her submission both a survival strategy and a source of quiet strength. Her brief act of rebellion—her pilgrimage to al-Husayn—reveals her longing for agency and connection, but also the costs of transgression. Her love for her children is both a comfort and a source of pain.

Yasin

Yasin, Ahmad's son by his first wife, is a man driven by appetite and haunted by the trauma of his parents' divorce. He seeks escape in women, drink, and indulgence, his excesses both a rebellion against and a mirror of his father's hidden life. Psychoanalytically, Yasin is the id unleashed, his inability to find satisfaction a symptom of deeper wounds and insecurities. His marriages end in betrayal and scandal, his search for love always undermined by self-destructive impulses. Yet he is also a source of humor and pathos, his failures both comic and deeply human.

Fahmy

Fahmy, the middle son, is the family's conscience and hope, a law student drawn to the ideals of nationalism and the dream of Egyptian independence. His love for Maryam is both personal and political, a symbol of his longing for a better world. Psychoanalytically, Fahmy represents the superego, his sense of duty and justice often at odds with the family's traditions and his father's authority. His involvement in the revolution brings pride and fear, and his death in a demonstration is both a personal tragedy and a symbol of the costs of change. His loss marks the end of an era for the family.

Khadija

Khadija, the elder daughter, is defined by her wit, energy, and sense of responsibility. She is both rival and protector to her sister Aisha, her sarcasm masking deep affection and insecurity. Psychoanalytically, Khadija is the ego negotiating between desire and duty, her longing for marriage and recognition often frustrated by circumstance. Her eventual marriage brings both relief and new challenges, as she navigates the complexities of family, tradition, and her own ambitions. Her resilience and humor are a source of strength for the family.

Aisha

Aisha, the younger daughter, is the family's beauty, her golden hair and blue eyes a source of pride and envy. She is dreamy and gentle, her passivity both a defense and a strategy for survival. Psychoanalytically, Aisha is the object of desire, her value defined by her appearance and her prospects for marriage. Her engagement and marriage are both fulfillment and loss, as she leaves home and must adapt to new roles and expectations. Her suffering is often hidden, her happiness fragile and contingent.

Kamal

Kamal, the youngest son, is both a participant in and a witness to the family's dramas. Curious, imaginative, and sensitive, he absorbs the contradictions of his world, his questions both childlike and profound. Psychoanalytically, Kamal is the emerging self, his identity shaped by the competing influences of tradition, authority, and change. His friendships, fears, and fantasies reflect the larger tensions of the novel, and his journey is one of awakening and adaptation.

Zaynab

Zaynab, Yasin's wife, is both a symbol of hope and a casualty of the family's dysfunction. Her pride and sense of self are tested by Yasin's infidelities and the double standards of the household. Psychoanalytically, Zaynab represents the costs of obedience and the limits of endurance, her decision to seek divorce both a personal and a social rupture. Her suffering exposes the vulnerabilities of women in a patriarchal society.

Maryam

Maryam, the neighbor's daughter, is the focus of Fahmy's romantic and political dreams. Her beauty and accessibility make her both a source of hope and a site of disappointment. Psychoanalytically, Maryam is the unattainable ideal, her eventual fall from grace a reflection of the novel's themes of disillusionment and the loss of innocence. Her story is both personal and emblematic of the changing world.

Ahmad's Friends (Jamil al-Hamzawi, Shaykh Mutawalli, etc.)

The friends and associates of Ahmad provide a chorus of commentary, their conversations reflecting the concerns, hopes, and anxieties of Cairo's middle class. They are both a support network and a mirror, their stories and jokes illuminating the broader social and political context. Psychoanalytically, they represent the superego of the community, enforcing norms and providing a space for negotiation and adaptation.

Plot Devices

Duality of Public and Private Selves

The novel's structure is built on the tension between public virtue and private vice, most notably in Ahmad's double life as a tyrannical patriarch and a secret hedonist. This duality is mirrored in the children's struggles with obedience and rebellion, and in the contrast between the family's rituals and their hidden desires. The use of interior monologue and shifting perspectives allows the reader to see the contradictions and complexities of each character, creating a rich psychological portrait. The home itself is both a sanctuary and a prison, its boundaries both enforced and transgressed.

Generational Conflict and Social Change

The plot is driven by the clash between tradition and modernity, as the younger generation seeks love, freedom, and political engagement in a world defined by patriarchal authority and social constraint. The family's internal conflicts—over marriage, obedience, and desire—are mirrored in the city's political turmoil, with the revolution serving as both backdrop and catalyst. The use of foreshadowing, especially in the depiction of the children's ambitions and the father's anxieties, heightens the sense of impending change and loss.

Symbolism of the House and City

The family home is both a symbol of stability and a site of repression, its rooms and rituals encoding the values and fears of its inhabitants. The city outside—Cairo's streets, mosques, and coffeehouses—is a world of possibility and danger, its rhythms and upheavals shaping the characters' lives. The use of windows, doors, and thresholds as recurring motifs underscores the themes of confinement and longing, while the rituals of daily life—meals, prayers, and celebrations—serve as both anchors and points of tension.

Narrative Structure and Perspective

The novel employs a third-person omniscient narrator, but frequently shifts focus among the characters, allowing for deep psychological insight and a multiplicity of perspectives. This narrative device creates empathy and complexity, as the reader is invited to understand the motives and contradictions of each family member. The use of interior monologue, dreams, and fantasies blurs the line between reality and imagination, highlighting the subjectivity of experience and the difficulty of communication.

Foreshadowing and Irony

Throughout the novel, moments of happiness are tinged with foreboding, and the characters' attempts to control their destinies are often undermined by fate and history. The father's insistence on order and obedience is repeatedly challenged by the unpredictability of love, desire, and political upheaval. The use of irony—both dramatic and situational—underscores the gap between intention and outcome, and the novel's ending is both inevitable and deeply moving.

Analysis

Palace Walk is a masterful exploration of family, authority, and the collision between tradition and modernity in early twentieth-century Cairo. Through the intimate portrait of the Abd al-Jawad family, Mahfouz examines the psychological costs of obedience, the double standards of patriarchy, and the longing for freedom—personal, sexual, and political. The novel's structure, with its shifting perspectives and rich symbolism, allows for a nuanced depiction of characters whose inner lives are as complex as the city they inhabit. The revolution outside mirrors the upheavals within, and the costs of change are measured in both private grief and public sacrifice. Mahfouz's insight into the dynamics of power, love, and loss is both universal and deeply rooted in Egyptian society, making Palace Walk a timeless meditation on the persistence of memory, the resilience of the human spirit, and the enduring quest for meaning in a world of uncertainty.

Last updated:

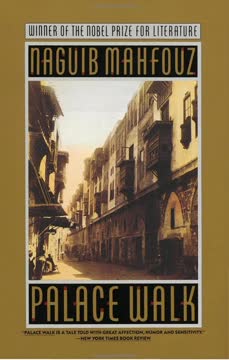

Review Summary

Palace Walk, the first volume of Naguib Mahfouz's Cairo Trilogy, follows the al-Sayyid Ahmad family in Cairo between 1917-1919. Readers praise Mahfouz's masterful character development, particularly the patriarch's striking hypocrisy—tyrannical at home yet jovial with friends, religiously strict yet engaging in drinking and womanizing. The submissive wife Amina and their five children each represent different aspects of Egyptian society. Reviews highlight the vivid descriptions of Cairo's neighborhoods and the integration of the 1919 Egyptian Revolution into family life. While some found the detailed descriptions occasionally slow, most consider it a masterpiece of Arabic literature.