Key Takeaways

1. The Washingtons' Hypocrisy: Liberty's Contradiction

"There is no re to really know the Washingtons without knowing this story.”

Founding paradox. George and Martha Washington, icons of American liberty, brought nine enslaved people, including Ona Judge, to Philadelphia, then the nation's capital. This move placed them in direct conflict with Pennsylvania's gradual abolition law, which mandated the emancipation of adult slaves after six months of residency. The Washingtons, unwilling to relinquish their human property, devised a clandestine scheme to circumvent this law.

Circumvention strategy. To avoid the six-month emancipation clause, the Washingtons regularly shuffled their enslaved individuals out of Pennsylvania and back to Mount Vernon, or to a neighboring slave state like New Jersey, effectively "resetting the clock" on their path to freedom. This calculated subterfuge, orchestrated by the President and his trusted secretary Tobias Lear, aimed to protect their financial investment and reputation while maintaining the convenience of enslaved labor in the North. Washington himself acknowledged the need "to deceive" the public if necessary, highlighting the moral compromises made to uphold slavery.

Moral dilemma. This practice exposed the profound hypocrisy at the heart of the American founding, where the ideals of freedom and equality coexisted with the brutal reality of human bondage. While Washington fought for national independence, he simultaneously fought to deny personal liberty to those he enslaved. His actions underscored the deep contradictions embedded in the nascent nation's values, revealing how even its most revered figures prioritized property rights over human rights.

2. Philadelphia: A Glimpse of Freedom's Promise

"Philadelphia represented the epicenter of emancipation, allowing black men and women the opportunity to sample a few of the benefits that accompanied a free status."

A new world. When Ona Judge arrived in Philadelphia with the Washingtons, she encountered a stark contrast to the plantation life of Mount Vernon. Philadelphia, a burgeoning city with a significant and growing free black population, was a hub of abolitionist sentiment and activity. This environment offered Ona her first real glimpse of what life outside of perpetual bondage could be like.

Exposure to liberty. Ona, Martha Washington's chief attendant, interacted with Philadelphia's sizable free black community, observing black entrepreneurs, attending newly erected black churches like "Bethel," and hearing stories of organizations like the Pennsylvania Abolition Society that actively helped enslaved people find or protect their freedom. These experiences profoundly shaped her understanding of liberty, making her "soon longed for liberation." The city's progressive laws, though imperfect, offered a tangible pathway to emancipation that was unimaginable in Virginia.

Seeds of discontent. The exposure to a world where black people could live freely, earn wages, and organize themselves planted seeds of discontent in Ona's mind. She witnessed white servants receiving pay and making decisions about their lives, a stark contrast to her own unpaid, controlled existence. This direct observation of freedom, coupled with the knowledge of Pennsylvania's gradual abolition law, fueled her growing desire to escape, transforming her perspective on her own enslavement.

3. Ona Judge's Courageous Choice for Freedom

"She was determined never to be her slave."

A grim future. Ona Judge's decision to flee was catalyzed by devastating news: Martha Washington intended to bequeath her as a wedding gift to her granddaughter, Eliza Custis Law. Eliza was known for her "stormy reputation," described as "stubborn" and "mercurial," with a "temperament difficult at best." This prospect of serving a volatile new mistress, coupled with the potential sexual vulnerability to Eliza's husband, Thomas Law, solidified Ona's resolve.

Risking everything. Ona understood the immense dangers of becoming a fugitive. She faced the threat of slave catchers, brutal punishment, and the possibility of being sold to the Caribbean, as Washington had done with other "difficult" slaves. Despite these terrifying prospects, her determination to avoid Eliza's ownership and secure her own liberty outweighed the risks. She later stated, "I knew that if I went back to Virginia, I never should get my liberty."

Unwavering resolve. Ona meticulously planned her escape in secret, packing her belongings while the Washingtons prepared for their return to Virginia. On Saturday, May 21, 1796, at the age of twenty-two, she slipped out of the President's Mansion during supper, disappearing into Philadelphia's free black community. This act of self-emancipation was a profound assertion of her agency, demonstrating an unyielding will to define her own life, free from the control of any master.

4. The First Family's Relentless Pursuit

"The ingratitude of the girl, who was brought up & treated more like a child than a Servant (& M™ Washington’s desire to recover her) ought not to escape with impunity if it can be avoided.”

Immediate alarm. Ona's escape sent shockwaves through the Washington household. Within days, Frederick Kitt, the Executive Mansion's steward, placed runaway advertisements in Philadelphia newspapers, describing Ona and offering a ten-dollar reward for her return, "whether white or black." The Washingtons were acutely aware that Ona's flight, especially from the President's household in a Northern city, could set a dangerous precedent for their other enslaved people and damage their public image.

Federal resources deployed. George Washington, despite being in his final months of presidency, personally directed the efforts to recapture Ona. He enlisted Secretary of the Treasury Oliver Wolcott Jr. and Portsmouth customs officer Joseph Whipple, leveraging federal authority and personal connections. Washington's letters revealed his anger and frustration, believing Ona had been "enticed away by a Frenchman" and that her "ingratitude" should not go "with impunity." He even suggested circumventing legal procedures, asking Whipple to put her "on board a Vessel bound immediately to this place—or to Alexandria."

Persistent pursuit. The Washingtons' pursuit was relentless, spanning years and involving multiple agents. Even after Ona had married and started a family in New Hampshire, Washington's nephew, Burwell Bassett Jr., was dispatched to retrieve her in 1799. This persistent effort, driven by Martha Washington's desire to reclaim her "body servant" and the President's concern for his property and reputation, underscored the lengths to which the nation's first family would go to maintain the institution of slavery.

5. The Perilous Reality of Fugitive Life

"She was a hunted woman and would try to pass, not for white, but as a free black Northern woman."

A life in shadows. Ona's journey to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, aboard Captain John Bowles's sloop, marked the beginning of a life lived in constant fear and anonymity. She shed her fine clothing, dressing inconspicuously to blend in, knowing that slave catchers and bounty hunters could appear at any moment. Her fair skin and demeanor allowed her to "pass for a free woman," but the threat of exposure was ever-present.

Hardship and vigilance. In Portsmouth, Ona faced the immediate challenges of finding shelter and work as a single black woman with limited resources. She quickly secured low-paying domestic labor, enduring physically taxing chores like scrubbing floors, washing laundry, and hauling heavy water containers—tasks far more arduous than her previous role as Martha Washington's personal attendant. Her days were filled with hard, honest labor, and her evenings were spent in vigilance, always aware of evening curfews for black residents and the need to avoid unwanted attention.

Close calls. The fear of recapture was not abstract. Ona had a terrifying encounter with Elizabeth Langdon, daughter of Senator John Langdon (a friend of the Washingtons), who recognized her in the streets of Portsmouth. This close call, and later the direct confrontation with Washington's nephew, Burwell Bassett Jr., forced Ona to rely on her quick thinking and the support of her community to evade capture, constantly reminding her of the precariousness of her freedom.

6. The Vital Role of Black and White Allies

"I never told his name till after he died, a few years since, lest they should punish him for bringing me away.”

Underground network. Ona's successful escape was not a solitary act but relied heavily on a network of sympathetic individuals. In Philadelphia, she confided in free black allies, likely including Reverend Richard Allen, a prominent black leader and entrepreneur, who provided crucial advice and possibly financial aid for her passage. These individuals risked severe penalties under federal law for harboring a fugitive slave.

Captain Bowles's role. Captain John Bowles, commander of the sloop Nancy, played a pivotal role in Ona's escape, transporting her from Philadelphia to Portsmouth. While not publicly known as an abolitionist, Bowles either turned a blind eye to her fugitive status or was sympathetic to her plight. Ona's decision to keep his name secret for decades, only revealing it after his death, underscores the danger he faced and her gratitude for his assistance.

Portsmouth's support. Upon arrival in Portsmouth, Ona was immediately "lodged at a Free-Negroes," indicating an established network ready to assist runaways. Later, when Washington's nephew attempted to forcibly return her, the local black community, and even Senator Langdon, discreetly warned her, allowing her to flee to Greenland and find refuge with the Jack family. These acts of defiance against federal law highlight the moral courage of those who prioritized human freedom over legal obligation.

7. The Personal Sacrifice of Family for Freedom

"Leaving them behind was the greatest of sacrifices."

Heart-wrenching choice. Ona's decision to escape meant severing ties with her entire family still enslaved at Mount Vernon. This included her mother, Betty, her sister Philadelphia, and her nieces and nephews. The guilt and sorrow of abandoning loved ones, knowing they remained in bondage, was a constant burden that "weighed constantly on her heart."

Unintended consequences. Ona's escape had direct, unforeseen consequences for her younger sister, Philadelphia. Martha Washington, angered by Ona's flight, assigned Philadelphia to serve Eliza Custis Law, the very mistress Ona had fled. Philadelphia was forced into the life her older sister had so vehemently rejected, highlighting the cruel ripple effect of slavery on families.

A life of longing. Despite building a new life and family in New Hampshire, Ona never forgot her Mount Vernon kin. The news of her brother Austin's death and her mother Betty's passing, though distant, would have deepened her sense of loss. Her freedom, while cherished, was perpetually tempered by the knowledge of her family's continued enslavement and the profound sacrifice she made to achieve her own liberty.

8. Marriage and Motherhood in Freedom

"For Judge, this was another example of freedom’s possibilities."

Building a new life. In Portsmouth, Ona found love and companionship with Jack Staines, a free black sailor. Their marriage in January 1797, though initially delayed by a cautious county clerk, was a profound act of self-determination. For Ona, it symbolized the "freedom's possibilities" that slavery had denied her—the right to choose a spouse, have a legally recognized union, and build a family.

Challenges of a sailor's wife. Jack Staines, a "black jack," provided for his family through seafaring, an occupation that offered opportunity but also meant long absences and inherent dangers like piracy, shipwrecks, and the risk of unlawful enslavement in Southern ports. Ona, now Ona Staines, had to navigate these periods of solitude, relying on her own domestic work and the support of her community to sustain her family and remain vigilant against slave catchers.

The bittersweet reality of children. Ona and Jack had three children: Eliza, Nancy, and William. The birth of her children was a joyous marker of freedom, allowing Ona to raise them according to her own will. However, the shadow of slavery persisted; despite being born free in New Hampshire, her children were legally considered enslaved property of the Custis estate, a cruel twist of fate that meant Ona could "never lay her worries about capture to bed."

9. Washington's Evolving Stance on Slavery

"To enter into such a compromise with her, . . . is totally inadmissible."

Conflicted ideals. George Washington, despite his relentless pursuit of Ona, harbored private misgivings about slavery. By the 1780s, he discussed his "growing unease" with lifelong enslavement with close friends like Tobias Lear and the Marquis de Lafayette. However, his personal discomfort did not translate into immediate action, as he remained unwilling to dismantle the institution during his lifetime.

Posthumous emancipation. Washington's final will, drafted in 1799, stipulated the eventual emancipation of his 123 personal slaves upon Martha's death. This decision, a significant departure from most slaveholders of his era, reflected his internal struggle with the moral implications of slavery. He provided for aged and young slaves, mandating that younger ones be taught to read and write and a useful occupation, indicating a degree of paternalistic concern for their future.

Limitations and contradictions. Despite this progressive step, Washington's will did not free the "dower slaves"—those inherited by Martha from her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis. These nearly 200 individuals, including Ona's family, remained enslaved and were eventually divided among Martha's grandchildren after her death. Washington's refusal to negotiate Ona's freedom, calling it "impolitic & dangerous precedent," further highlighted the limits of his evolving views when confronted with direct challenges to his authority and property rights.

10. Ona's Enduring Spirit: A Testament to Self-Emancipation

"No, I am free, and I have, I trust, been made a child of God by the means."

Unwavering conviction. Ona Judge Staines lived for 52 years as a fugitive, enduring poverty, the loss of her husband, and the indentured servitude of her daughters. Yet, when asked if she regretted leaving Washington, her response was resolute: "No, I am free, and I have, I trust, been made a child of God by the means." This powerful statement encapsulated her unwavering belief in the inherent value of freedom, regardless of the hardships it entailed.

Literacy and faith. In her later years, Ona found solace and strength in Christianity and literacy, two aspects of freedom denied to her in bondage. She learned to read the Bible, which she linked to her "salvation," and even questioned George Washington's religious devotion, noting she "never heard Washington pray." Her strong faith provided a moral compass and a source of resilience in her challenging life.

A voice for freedom. In the 1840s, Ona, then in her early seventies and with her children deceased, emerged from the shadows to share her story. She granted interviews to abolitionist newspapers like the Granite Freeman and The Liberator, permanently linking her narrative to the broader crusade for black freedom. Her oral testimony, a rare firsthand account of an 18th-century Virginia fugitive, served as a powerful testament to the human spirit's insistence on liberty, inspiring thousands in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Last updated:

Review Summary

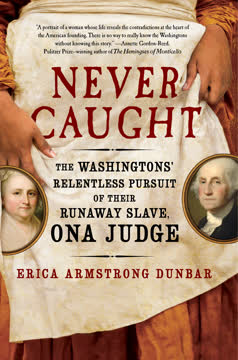

Never Caught receives mixed reviews (3.83/5). Readers praise Erica Armstrong Dunbar for bringing Ona Judge's compelling story to light and exposing the Washingtons' complicity in slavery. However, many criticize extensive speculation about Judge's thoughts and feelings due to limited source material. Reviewers note repetitive writing, excessive focus on the Washingtons rather than Judge, and frustration that Judge's original interviews aren't included in full. Some find it too basic or padded, while others appreciate its accessibility and historical value in humanizing slavery's impact.