Key Takeaways

1. Cultural Periods Accelerate, Leading to Postmodern Exhaustion

The last period to be distinguished and studied by cultural critics is called the postmodern period, and it is on this period that I would like to dwell for a moment.

Historical acceleration. Human history, particularly Western cultural production, can be understood through distinct periods, which are emerging and evolving at an accelerating pace. From millennia-long premodern eras to centuries-long modern phases, we now experience cultural shifts in mere decades, driven by technological advancement and societal complexity. This rapid succession, however, has not led to a utopian "singularity" but rather to widespread confusion, alienation, and psychic fragmentation.

Postmodern ubiquity. The postmodern period, spanning roughly the mid-1900s to the early 2000s, became a ubiquitous term in academia, yet its meaning remained elusive due to its deliberate resistance to neat definitions and its wide-ranging application across diverse phenomena like pop art and linguistic theory. Despite this, "postmodern" colloquially retained a distinct character of subversiveness, incomprehensibility, irreverence, irony, and cynicism, marking it as a discrete cultural modifier.

Critique and exhaustion. By the 1990s, influential figures like David Foster Wallace began critiquing postmodernism's core strategies, particularly cynical irony, which he argued had lost its emancipatory power and become complicit with consumer capitalism. Cultural theorists like Linda Hutcheon declared the "postmodern moment" over by 2002, recognizing its discursive strategies persisted but a new label was needed for the emerging "post-postmodern" era. This exhaustion signaled a readiness for a new cultural paradigm.

2. Postmodernism: The Loss of Transcendence and Deeper Meaning

For Lyotard, this was the grand narrative; for Harvey, the eternal and unchanging; for Jameson, the deeper meaning.

A period of subtraction. Postmodernism, as articulated by key thinkers, is fundamentally defined by a series of losses. Jean-François Lyotard described it as "an incredulity toward metanarratives," a loss of belief in overarching stories that once oriented society. David Harvey saw it as the abandonment of "eternal and immutable" elements in modern life, embracing flux and contingency. Fredric Jameson identified it as the loss of the "hermeneutic model," where "depth is replaced by surface," leading to a world of appearances without deeper meaning.

Total immanence. These individual losses collectively point to a singular, profound absence: the removal of "transcendence, broadly conceived," or "what the religions call God," from cultural production. Postmodernism represented the culmination of modernity's "disenchantment" and secularization, resolving the transcendence/immanence dialectic into a one-dimensional monism of total immanence. This collapse eliminated ontological "dimensionality," leading to a world without inherent depth, eternal possibilities, or grand narratives of meaning.

Cynicism and superficiality. The prevailing ethos of postmodernism was cynical, relentlessly ironic, self-referential, and world-weary, taking few things seriously. It celebrated the commercialization of life, dealt in surfaces and simulations, and was disillusioned with lofty ideals. This cultural logic, described by Jameson as "the cultural logic of late capitalism," presented an endless stream of superficial "moments" and purchases, where deeper meaning was deemed futile, contributing to a pervasive sense of boredom punctuated by novel chaos.

3. The Metamodern Turn: A Call for Trust and Re-engagement

A different, more productive answer to this antagonistic impasse, Hassan concludes, will need to lie in “words that we have forgotten in academe, words that need, more than refurbishing, reinvention. I mean words like truth, trust, spirit, all uncapitalized.”

Beyond cynicism. The exhaustion of postmodernism, marked by its pervasive cynicism and fragmentation, created an urgent need for a new cultural approach. Ihab Hassan, a bridge figure, argued for a "hermeneutics of trust" to counter the "specter of Identity" and incessant factionalism that postmodernism's "micronarratives" had exacerbated. He called for the reinvention of concepts like "truth," "trust," and "spirit," but "all uncapitalized," signaling a departure from metaphysical absolutes.

Nihilism overcome. Hassan proposed that this new spirit could emerge not by retreating from nihilism, but by passing through it. His "via negativa" approach to spirit, associating it with nothingness, offered a bridge from postmodern nihilism to a new kind of spiritual transcendence. By recognizing that "fiduciary realism" rests on "Nothingness, the nothingness within all our representations," one could find a shared basis for trust and empathy, moving beyond the solipsistic gaps created by postmodern fragmentation.

Progressive re-engagement. This metamodern sensibility, therefore, is not a reactionary return to old ways but a progressive re-engagement with fundamental human needs for connection and meaning. It acknowledges postmodern critiques while seeking to move "beyond" them. This "hermeneutics of trust" becomes a precondition for considering post-postmodern paradigms, inviting openness to new ideas that might otherwise be dismissed by ingrained postmodern cynicism.

4. Transcendence Returns, But in Two Distinct Forms

This dissatisfaction and disillusionment with postmodern immanence has thus occasioned the return of what I call “ontological dimensionality,” the non-monistic, multi-planer mapping of reality that allows for some relationship between different modes of existence (and thus depth, meaning, even teleology).

Re-establishing dimensionality. The widespread dissatisfaction with postmodernism's total immanence and its resulting "meaning crisis" has led to a powerful resurgence of "ontological dimensionality." This signifies a cultural yearning for a multi-layered reality, where different modes of existence can relate, thereby reintroducing concepts of depth, meaning, and purpose that were lost in the postmodern flattening of experience.

Two paths of return. This return of transcendence is manifesting in two distinct forms:

- Regressive/Reactionary: A conservative backlash that simply re-posits traditional transcendentals like Truth, Reason, Progress, and God (all capitalized). These ideas, marginalized during postmodernism, are now finding a wider audience among those seeking familiar anchors.

- Progressive/Metamodern: A forward-looking approach that confronts postmodern critiques and seeks a post-metaphysical model of transcendence. This involves finding "immanent transcendence" or "sub-dimensionality" within the immanent frame itself, often expressed through concepts like "outer/inner," "constituent/emergent," or "helpful constructs."

Reinvented spirit. The progressive metamodern response aims for a "reinvented" transcendence, one that has been "baptized in the fires of immanence." It seeks depth and meaning without resorting to discredited metaphysical illusions. This new form of dimensionality allows for a renewed sense of purpose and identity, not by denying postmodern insights, but by integrating them into a more complex and nuanced understanding of reality.

5. Art After Postmodernism: Reinventing Spirituality and Depth

The Remodernist’s job is to bring God back into art but not as God was before.

Remodernist revival. The Remodernism movement, articulated by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson in 2000, directly challenged the institutionalized postmodern avant-garde. They called for a return to modernist principles, emphasizing "vision as opposed to formalism" and seeking a "new spirituality in art" that embodies "spiritual depth and meaning." This was a direct rejection of postmodernism's "scientific materialism, nihilism, and spiritual bankruptcy," advocating for an art that connects, includes, and addresses the "travails of the human soul."

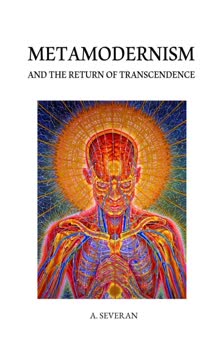

Visionary art's mission. Alex Grey's visionary art movement exemplifies a progressive re-engagement with transcendence. Moving from postmodern nihilism to mystical experiences, Grey's work translates these "visions" into vibrant art aimed at collective transformation. His "Mission of Art" calls for artists to move beyond "slickness, cleverness, and nihilism" to offer art as "medicine to heal the alienation and sickness of the human soul," emphasizing an embodied, immanent transcendence that reveals the spiritual within the material.

Kitsch and Post-Contemporary realism. The "Kitsch movement," led by Odd Nerdrum, and the broader "Post-Contemporary" art tradition, embraced figurative realism and traditional craft, rejecting postmodern conceptual art. These artists, like Adam Miller and Luke Hillestad, sought to represent "the sincere timeless human condition" and "re-construct meaningful traditions." Their work, often neo-Romantic, aims to create beautifully crafted narratives of self-discovery and collective transcendence, demonstrating a commitment to expressing transcendent themes in novel, historically informed ways.

6. Performatism: Experiencing Transcendence Through Aesthetic Frames

Performatism…replaces Postmodern irony and skepticism with artistically mediated belief and the experience of transcendence.

Aesthetically mediated belief. Raoul Eshelman's theory of performatism identifies a post-postmodern cultural phase where "artistically mediated belief" allows for the experience of transcendence. It posits that while metaphysical transcendence may be logically untenable, art can create fictional conditions—through techniques like "double framing" and "theistic plots"—where notions of Truth, Trust, Beauty, and Spirit can be viscerally experienced within the aesthetic work. This means art becomes the new "locus of spirit."

Bracketing skepticism. Performatist works ingeniously anticipate and forestall postmodern deconstruction by performing it themselves. They present metaphysical ideas openly, not as logical arguments, but as experiences to be felt. The audience is "practically forced to identify with something implausible or unbelievable within the frame – to believe in spite of yourself – but...intellectually you remain aware of the particularity of the argument at hand." Skepticism is not eliminated but "held in check by the frame," allowing for a temporary, aesthetic suspension of disbelief.

From art to reality. The power of performatism lies in its potential to transform belief patterns. After experiencing transcendence within the art's constructed frame, the audience is left to decide how to integrate this experience into their disenchanted world. If accepted, this "interiority may then be projected back onto the outside contexts around it," potentially changing reality itself. This existential choice, to say "yes" to an experienced transcendence, becomes an act of identity-construction, opening new avenues for meaning beyond purely immanent markers.

7. Metamodernism's Core: Oscillating Between Modern Hope and Postmodern Irony

Ontologically, metamodernism oscillates between the modern and the postmodern. It oscillates between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naivete and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity.

The oscillation metaphor. Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker's metamodernism provides a comprehensive framework for the post-postmodern era, characterized by a continuous "oscillation" between modern and postmodern sensibilities. This dynamic movement, like an LED message clock, creates a seemingly stable message from rapidly shifting poles. It embodies an "informed naivety" and "pragmatic idealism," balancing modern enthusiasm with postmodern irony, hope with melancholy, and unity with plurality.

Return of depthiness. Metamodernism signals a return of depth, but a new kind of depth, termed "depthiness." Unlike Jameson's "depthlessness" of postmodernism, "depthiness" is not an epistemological quality but a "performative act," a "truth" produced by emotion rather than empiricism. Metamodern thinkers and artists "resurrect [depth's] spirit" by creating "personal, alternative visions of depth," acknowledging the flattening of old metaphysical models while reanimating their ghost in new, immanent ways.

Neo-Romantic sensibility. This shift in sensibility leads to an abandonment of postmodern deconstruction and pastiche in favor of "reconstruction, myth, and metaxis." Metamodernism finds its clearest expression in a Neo-Romantic sensibility, which oscillates between the finite and the infinite, recognizing the impossibility of full realization. This is not mere re-appropriation or nostalgia, but a "re-signification" of the commonplace with mystery, opening "new lands in situ of the old one," reflecting a progressive, forward-looking engagement with historical forms.

8. The Specter of Identity Drives Metamodern Cultural Production

The first feature crucial to our metamodern moment that I would like to draw out is the ‘specter of Identity’ that haunts it.

Longing for heritage. A metamodern generation, deprived of identity in postmodern consumer culture, exhibits a profound longing for things with history, depth, and character. This manifests as an attraction to "retro" aesthetics and a reinvigoration of craft, rejecting homogenized consumption in favor of small-scale, DIY production. This thirst for identity through heritage connects to historical sensibilities where transcendence was engaged, serving as a crucial means of self-differentiation and community building.

Craft and authenticity. The resurgence of craft, from Etsy marketplaces to craft beer and modern homesteading, reflects a rejection of postmodern commodification. These methods, imbued with the "aura of history and tradition," demand greater effort, establishing boundaries and status markers for differentiated communities. They also activate resonances with historical sensibilities that engaged transcendence, speaking to an existential aspiration starved during postmodernism, and are crucial for identity-construction.

Cultural fissures. This intense longing for identity, however, has become a volatile front in contemporary culture wars. The political landscape of early metamodernity is characterized by deep cultural blocs and ideological parties, often rooted in crudely negotiated identity formations. This polarization, occurring amidst mounting global crises, sacrifices effective political action to division and gridlock, highlighting the urgent need for more cohesive and integrated frameworks for identity.

9. Metamodernism as a Political and Developmental Project

Hanzi’s metamodernism is a developmental metamodernism, which articulates the emerging metamodern sensibility first described by Vermeulen and van den Akker not as a mere cultural period, but as a distinct developmental stage now manifesting in cultural history through its emergence in enough individuals operating at this particular stage of cognitive complexity.

Beyond description. While Vermeulen and van den Akker's metamodernism primarily describes a cultural sensibility, figures like Hanzi Freinacht (Daniel Görtz and Emil Ejner Friis) have transformed it into a prescriptive philosophical system and political project. Hanzi's "ironic sincerity" exemplifies the metamodern oscillation, allowing for earnest articulation of grand narratives and bold political visions, tempered by postmodern critiques. This "informed naivete" and "pragmatic idealism" aim to move beyond the postmodern impasse.

Developmental metanarrative. Hanzi's "developmental metamodernism" frames the emerging sensibility not just as a cultural period but as a distinct stage of cognitive complexity in human development. This metanarrative underpins his political vision for a "listening society," which leverages political resources for human self-actualization and developmental growth. It seeks to heal identity-driven cultural divides by addressing disparities in development and limitations of self-constructions, even exploring their spiritual roots.

Liminal web and meta-crisis. This action-oriented metamodernism thrives outside traditional academia, utilizing online hubs, forums, and podcasts (e.g., Metamoderna, Rebel Wisdom). This "liminal web" actively engages the "meta-crisis"—a confluence of global climate emergency, wealth inequality, institutional decay, and meaning-making crises. These challenges, exacerbated by modernism and postmodernism, provide the impetus for metamodernists' idealistic yet pragmatic efforts toward broad cultural transformation.

10. Aesthetically-Mediated Belief: Art as the New Locus of Spirit

To say it once and for all: art is the new locus of spirit.

Phenomenological counter. A core element of metamodernism is the shift of transcendence from objective metaphysics to subjective, phenomenological experience, often mediated by aesthetics. This "performatism of aesthetically-mediated belief" allows for the return of depth, truth, and spirit, but in a qualified, "uncapitalized" form. It's an outbreak of idealism, but pragmatic; a sense of naivete, but informed, where vulnerability and earnestness become subversive in the face of corporate co-option.

Art as spiritual conduit. Metamodern art actively translates mystical experiences and spiritual aspirations into aesthetic forms. Visionary artists like Alex Grey, for instance, build communities around "Art Church" and construct hybrid spaces like Entheon (art gallery/spiritual temple), demonstrating how art literally mediates engagement with the divine. This approach grounds spirituality in the material, aesthetic realm, making it accessible and efficacious for cultural transformation.

Contrived depth. Whether through Remodernist calls to bring "God back into art but not as he was," or performatist works creating special frames for transcendence, metamodern art embraces "contrived depth." It acknowledges the artificiality of its constructs while leveraging them to induce genuine experiences of meaning and connection. This courageous vulnerability and guarded optimism characterize a youthful movement dedicated to a "distinctly metamodern transcendence," unscripted and unbought.

11. Metamodern Mythmaking: Crafting New Narratives for a Crisis-Ridden World

In metamodern mythopoeia, mythologies are invented: liturgies, hymns, ceremonies, scriptures, deities, all as an artist paints a scene.

Reconstruction of meaning. The metamodern moment is characterized by a "mythopoeic turn," a project of actively constructing new myths and paradigmatic models for the twenty-first century. This "metamodern mythopoeia" embraces both postmodern doubt and modernist optimism, creating new mythic systems of meaning that induce depth and sublimity. "Theology" becomes a creative, exploratory act, performed for the sensation within the immanent realm, generating an almost convincing sense of transcendence.

Fragile theism. Metamodern mythmaking never definitively affirms or rejects grand narratives of faith. This inherent ambiguity is crucial, as "metamodern faith must presume a kind of atheism if one is to have the freedom to create ‘God’." The resulting "fragile theism" remains malleable, resisting ossification into naive religious conceptions, and instead thrives in a dynamic oscillation between belief and critical scrutiny.

Artistic mythologies. Contemporary artists like Martin Wittfooth, Adam Miller, and Billy Norrby exemplify this trend, employing traditional mythic iconography to frame modern critiques and visions. Wittfooth's Pieta recontextualizes a religious trope to indict ecological destruction, while Miller's The Roses Never Bloomed So Red inverts traditional narratives to champion nature. Norrby's Rise elevates contemporary rebellions to heroic status. These artists use symbol and traditional craft as "aesthetic rebuke and rebellion against postmodern kitsch," offering metamodern neo-Romanticism and "contrived depth" to address urgent societal needs.

Last updated: