Key Takeaways

1. Embrace the Scientific Method for Superior Cocktails.

THINK LIKE A SCIENTIST AND YOU WILL MAKE BETTER DRINKS.

Lifelong journey. Approaching cocktails as problems in need of solutions transforms bartending into a lifelong journey of inquiry. The more you learn, the more questions arise, pushing you towards an unattainable but inspiring goal of perfection. This mindset encourages continuous learning, practice, and observation.

Scientific approach. You don't need to be a scientist to apply the scientific method to cocktail creation. The core principles involve controlling variables, observing results, and testing outcomes. This systematic approach ensures consistency, improves existing recipes, and enables the development of delicious new drinks without relying on random guesswork.

Purposeful innovation. New techniques and technologies should only be employed if they genuinely enhance the drink's taste. The focus remains on crafting amazing drinks with fewer, rather than more, ingredients, ensuring the guest's enjoyment is paramount, not the novelty of the method. Mistakes are often the origin of the best ideas, fostering a culture of persistent questioning and learning.

2. Precision in Measurement Ensures Consistency and Control.

In a professional setting, it is essential that your drinks be consistent.

Volume over weight. While cooking often benefits from weighing ingredients, cocktails are best measured by volume. This is because pouring small volumes is faster, and the density of cocktail ingredients varies wildly. Consistent volume ensures a proper "wash line" (liquid level) in the glass, providing an instant visual check for accuracy and fairness to guests.

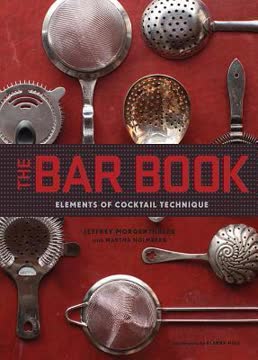

Accurate tools. For individual drinks, jiggers are standard, but choosing tall, skinny jiggers over short, squat ones significantly increases accuracy. For recipe development and batching, graduated cylinders are superior to measuring cups and beakers. Advanced tools like micropipettes offer extreme precision for concentrated flavors, allowing for fine-tuning of complex recipes.

Standardized units. American cocktail recipes typically use ounces, which can be thought of as "parts" for ratio-based mixing. The author standardizes 1 ounce to 30 milliliters, simplifying conversions for batching. This consistent unit system, along with precise measurements for bar spoons, dashes, and drops, allows for repeatable results and nuanced recipe adjustments.

3. Ice is the Unsung Hero: Master Its Science for Optimal Chilling and Dilution.

The amount of ice that melts in a given length of time is proportional to how much heat gets transferred into the ice.

Clear vs. cloudy. Historically, lake ice was prized for its clarity, a quality often missing in modern freezer ice. Clear ice forms slowly, layer by layer, pushing out impurities and trapped gases. Cloudy ice, formed rapidly, traps these impurities, making it prone to shattering and inconsistent dilution. Making clear ice at home involves freezing large blocks in insulated containers, allowing slow, directional freezing.

Chilling power. Ice at 0°C can chill a cocktail below 0°C due to the interplay of heat (enthalpy) and disorder (entropy) when alcohol is introduced. Every gram of melted ice provides significant chilling power (80 calories), making it a miraculous substance for cooling. However, the rate of chilling and dilution depends on the ice's surface area and agitation.

Dilution control. Smaller ice pieces have more surface area, chilling faster but also carrying more surface water, leading to inconsistent dilution. To mitigate this, always shake off excess surface water from ice before use. Large, freshly cracked ice minimizes "holdback" (cocktail trapped on ice) and allows for more controlled dilution, crucial for consistent drink quality.

4. Shaken, Stirred, Built, Blended: Each Technique Dictates a Drink's Unique Profile.

THERE IS NO CHILLING WITHOUT DILUTION, AND THERE IS NO DILUTION WITHOUT CHILLING.

The Fundamental Law. Chilling and dilution are inextricably linked in traditional cocktails. This means that for a given recipe, if two drinks reach the same final temperature, they will have the same dilution, regardless of the specific stirring or shaking technique used. This principle underpins the structure of all traditional cocktails.

Technique profiles.

- Stirred drinks (e.g., Manhattan, Negroni): Gentle chilling and dilution, no aeration. Aim for medium-sized, relatively dry ice. Served relatively warm (-5°C to -1°C) and boozy (21-29% ABV).

- Shaken drinks (e.g., Daiquiri, Whiskey Sour): Violent agitation for rapid chilling, significant dilution, and aeration (texture/foam). Require foam-enhancing ingredients like citrus juice or egg white. Served colder and more diluted (15-20% ABV).

- Built drinks (e.g., Old-Fashioned): Minimal dilution, poured directly over ice in the serving glass. Designed for slow evolution as ice melts. Very boozy (27-32% ABV) and typically contain little to no acid.

- Blended/Shaved drinks (e.g., Margarita): Extremely efficient chilling and dilution, producing very cold, slushy textures. Require recipe adjustments (more sugar, less acid, less liquid) compared to shaken versions.

Texture and temperature. Beyond dilution, each technique imparts a distinct texture and ideal serving temperature. Shaking introduces air bubbles and foam, which are fleeting. Stirring aims for limpid clarity. Temperature dramatically affects taste; some drinks (like Manhattans) suffer when too cold, while others (like Negronis) lose appeal when too warm.

5. Rapid Infusions Unlock Intense, Balanced Flavors in Minutes, Not Weeks.

Rapid infusion tends to extract bitter, spicy, and tannic components less than long-term infusion does.

Pressure manipulation. Rapid infusion techniques leverage pressure changes to quickly extract flavors from solids into liquids, or impregnate solids with liquids. The iSi cream whipper, using nitrous oxide (N2O), is ideal for liquid infusions, while a vacuum machine excels at infusing solids. These methods drastically reduce infusion times from days or weeks to mere minutes.

Nitrous infusion (iSi). N2O, a water/ethanol/fat-soluble gas, dissolves into liquid under pressure, forcing the liquid into the pores of a solid. Releasing the pressure causes the N2O to boil out, pushing the newly flavored liquid back out of the solid. This process preferentially extracts aromatic and top notes, minimizing bitter, spicy, or tannic compounds, making it excellent for ingredients like turmeric, lemongrass, or coffee.

Vacuum infusion. This technique involves placing a porous solid (e.g., cucumber, pineapple) in a flavorful liquid within a vacuum chamber. The vacuum removes air from the solid's pores, and upon release, atmospheric pressure forces the liquid into these empty spaces. This transforms the solid's flavor and appearance, making it translucent and jewel-like, perfect for garnishes or "edible cocktails."

6. Clarification Transforms Drinks: Aesthetics, Carbonation, and Texture Depend on It.

Clarification removes these particles.

Beyond aesthetics. Clarification is the process of removing suspended particles that make liquids cloudy. While it enhances visual appeal, its importance extends to function: clarified liquids are essential for stable carbonation, as particles act as nucleation sites for excessive foaming. It also refines mouthfeel, preventing drinks from feeling "chewy" or pulpy.

Mechanical and gel methods. Clarification primarily relies on three mechanical means:

- Filtration: Blocking particles, but often slow and prone to clogging.

- Gelation: Trapping particles within a gel matrix. Agar-based gels are preferred over gelatin for their porous structure, faster setting, and heat resistance, allowing for "quick agar clarification" in under an hour.

- Density separation: Using gravity or centrifugal force to settle particles.

Enzymatic assistance. For most fruit and vegetable juices, enzymes like Pectinex Ultra SP-L (SP-L) are game-changers. SP-L breaks down pectin, hemicellulose, and cellulose, which stabilize cloudy particles and thicken juices. This allows for effective clarification even with lower-force centrifuges (around 4000 g's) and significantly increases clarified juice yield.

7. Booze Washing Selectively Refines Spirits, Enhancing Texture and Mellowing Harshness.

Milk washing, therefore, has two purposes: it reduces astringency and harshness, and it augments the texture of shaken drinks.

Targeting polyphenols. Booze washing is a technique to selectively strip unwanted flavors, particularly astringent polyphenols, from spirits. These compounds, found in tea, oak-aged spirits, and some fruits, can become overpowering in cocktails, especially when cold or carbonated. Washing agents bind to these polyphenols, allowing for their removal.

Three primary methods:

- Milk Washing: Adding liquor to milk (not vice-versa) causes milk proteins (casein) to curdle and bind with polyphenols. Straining the curds leaves a clear spirit with reduced astringency and enhanced foaming properties due to residual whey proteins, ideal for shaken drinks.

- Egg Washing: Similar to milk washing, egg whites coagulate and strip tannins. A 20:1 liquor-to-egg white ratio is effective for mellowing aged spirits without obliterating their character. Egg-washed spirits are also suitable for carbonation, as they leave minimal foaming proteins.

- Chitosan/Gellan Washing: A two-step process using positively charged chitosan to attract negatively charged oak polyphenols, followed by negatively charged gellan gum to bind and remove the chitosan. This method effectively mellows harsh oakiness in spirits, making them suitable for carbonation without the flavor loss of distillation.

Fat washing. This related technique infuses desirable flavors from a fat into a liquor. By combining a flavorful fat (e.g., bacon fat, olive oil) with a spirit, allowing it to infuse, and then chilling to solidify the fat for easy removal, unique flavored spirits can be created.

8. Mastering Carbonation Requires Understanding the "Three C's" for Perfect Bubbles.

Nine-tenths of good carbonation is foam control.

Carbonation as taste. Carbonation is a distinct taste, not just a sensation, sensed by specific receptors in our mouths. The amount of dissolved CO2 dictates its "prickliness." While commercial mixers often fall short, self-carbonation allows precise control over bubble intensity, which is crucial as too much carbonation can destroy delicate flavors or overemphasize harsh notes.

The Three C's. Achieving optimal carbonation and preventing excessive foaming relies on:

- Clarity: Particles in a drink act as nucleation sites, causing rapid CO2 release and gushing. Clarifying liquids before carbonation is paramount for stable, long-lasting bubbles.

- Coldness: Colder liquids hold more CO2 without foaming. Drinks should be chilled as close to their freezing point as possible (e.g., -6°C to -10°C for cocktails) to maximize CO2 retention and minimize foam.

- Composition: Certain ingredients (proteins, emulsifiers, viscous liquids) promote foaming. Alcohol also increases foaming while simultaneously requiring more CO2 to taste carbonated. Keeping alcohol levels moderate (14-17% ABV) helps manage foam.

Technique for success. Effective carbonation involves repeatedly pressurizing and agitating the drink (e.g., shaking a bottle connected to a CO2 tank), followed by venting to release trapped air and excess foam. This multi-step process "scrubs" nucleation sites, leading to strong, stable, and foam-resistant carbonation that lasts in the glass.

9. Beyond Liquor: Sweeteners, Acids, and Salt are Critical for Cocktail Balance.

Salt is the secret ingredient in almost all my cocktails.

Sweeteners. Most cocktails contain sweetness from various sugars (sucrose, glucose, fructose). Temperature significantly impacts perceived sweetness; colder drinks taste less sweet, requiring more sugar. Syrups (1:1 or 2:1 sugar-to-water by weight) are preferred over granulated sugar for rapid dissolution and consistent pouring. Agave nectar, high in fructose, behaves uniquely, maintaining sweetness at colder temperatures.

Acids. Acids provide tartness and balance. Common cocktail acids include:

- Citric acid (lemon-like, fast attack)

- Malic acid (green apple-like, lingers)

- Tartaric acid (grape-like)

- Lactic acid (fermented notes)

- Acetic acid (vinegar, aromatic)

Different combinations create distinct flavor profiles (e.g., citric + malic = lime). pH meters are useless; titratable acidity (amount of acid molecules) is what the tongue senses.

Salt: the secret weapon. A pinch of salt, or a few drops of saline solution, is a subthreshold enhancer for most cocktails, especially those with fruit, chocolate, or coffee. It doesn't make the drink taste salty but makes other flavors "pop," demonstrating its profound impact on overall balance.

10. Cocktail Calculus: Recipes are Mathematical Structures for Predictable Excellence.

I discovered that given a set of ingredients and a style of drink, I can write a decent recipe without tasting along the way at all.

Structural analysis. Cocktail recipes, regardless of their specific flavors, adhere to predictable mathematical relationships concerning alcohol content (ABV), sugar, acidity, and dilution. By analyzing dozens of classic and modern recipes, the author identified consistent profiles for different drink styles (built, stirred, shaken, blended, carbonated).

Predictive power. Understanding these underlying structures allows for the creation of new recipes with a high degree of accuracy, even before tasting. For example, knowing the target ABV, sugar, and acid levels for a "shaken sour" profile enables the construction of a balanced drink using novel ingredients, even if the specific flavors are new.

Key parameters for balance:

- Ethanol: Dictates dilution and temperature (higher ABV = less dilution = warmer).

- Sugar: Higher in colder drinks to compensate for dulled perception.

- Acid: Less affected by temperature than sugar; often scaled back more in highly diluted drinks.

- Dilution: Directly linked to chilling; varies significantly by drink style.

This "cocktail calculus" provides a robust framework for recipe development and adaptation, ensuring structural integrity while allowing for creative freedom in flavor selection. The math provides the backbone; the aromatics and flavors provide the soul.

Last updated:

Review Summary

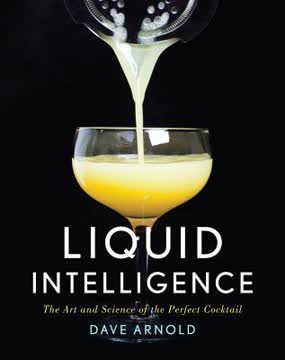

Liquid Intelligence is highly praised for its scientific approach to cocktail making. Readers appreciate Arnold's detailed explanations of techniques, from ice formation to clarification. While some find the book overwhelming or impractical for home use, many consider it essential for serious cocktail enthusiasts and professionals. The book's depth of knowledge, innovative techniques, and engaging writing style are frequently commended. Some readers note safety concerns with certain methods. Overall, it's regarded as a groundbreaking work that elevates cocktail making to a science.