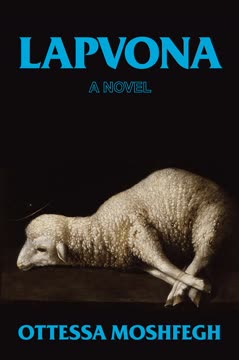

Plot Summary

Blood and Bandits' Easter

On Easter, bandits attack the village of Lapvona, leaving behind a trail of blood and grief. The villagers, already poor and vulnerable, are left to mourn their dead, including children. Marek, a deformed and sensitive boy, witnesses the aftermath and is haunted by the violence. His father, Jude, a harsh and pious lamb herder, teaches him that suffering is a path to God, but offers little comfort. The village's pain is compounded by the knowledge that their lord, Villiam, remains untouched in his manor, protected by guards who never intervene. The event sets the tone for a world where cruelty, faith, and power are inextricably linked, and where the innocent suffer for the whims of those above.

The Lamb Herder's Curse

Jude, Marek's father, is a man broken by loss and bitterness. He raises Marek with a stern hand, believing that pain and deprivation are the only ways to earn God's favor. Jude's love is twisted, manifesting as both physical abuse and a refusal to let Marek see his own reflection, convinced that beauty is sinful. Marek, desperate for affection, internalizes his father's cruelty, seeking punishment as a form of love. Their relationship is a cycle of violence and repentance, with Marek longing for a mother he never knew and Jude haunted by the absence of Agata, Marek's mother, who he claims died in childbirth. The pasture, their home, is both sanctuary and prison, echoing with the cries of lambs and the weight of unspoken sins.

The Blind Nurse's Milk

Ina, the village's blind wet nurse, is a figure of myth and necessity. Surviving plague and abandonment, she learns to navigate the world through birdsong and touch, becoming a healer and provider for generations of Lapvonians. Her milk is legendary, nourishing not just infants but the community's sense of continuity. Marek, rejected by his father, finds solace in Ina's care, returning to her even as a teenager for comfort and a semblance of maternal love. Ina's wisdom and otherness make her both revered and feared, a woman who straddles the line between witch and saint. Her presence is a reminder of the village's dependence on the mysterious and the feminine, even as they distrust what they cannot control.

The Beating and the Bandit

After witnessing the bandit's execution, Marek is moved to pity, offering forgiveness where others demand vengeance. His empathy is met with violence at home, as Jude punishes him for perceived weakness. The cycle of abuse is both personal and communal, with the village's suffering mirrored in Marek's body. The story of Agata, Marek's mother, is revealed as a fabrication, a means for Jude to cast himself as a tragic hero. The truth of Agata's fate—her escape and survival—remains hidden, a secret that will later unravel the fragile identities of father and son. Marek's longing for connection and meaning is continually thwarted by the harsh realities of Lapvona's world.

Jacob's Fall from Grace

Marek's uneasy friendship with Jacob, the privileged son of Lord Villiam, is marked by admiration, resentment, and manipulation. Jacob's casual cruelty and Marek's internalized self-loathing culminate in a fatal accident: Marek, provoked and desperate, throws a rock that causes Jacob to fall to his death. The event is both an accident and an act of suppressed rage, a moment where the powerless briefly seize agency with tragic results. The aftermath is a tangle of lies, guilt, and shifting allegiances, as Jude and Marek must face the consequences of a crime that cannot be undone. The death of Jacob sets in motion a chain of events that will upend the social order of Lapvona.

The Lord's Exchange

Jude, seeking to save himself, brings Jacob's body to Villiam and confesses Marek's role in the death. In a display of lordly caprice, Villiam proposes an exchange: Marek becomes his son, and Jude takes Jacob's corpse. The transaction is both absurd and chilling, reducing human life to property and spectacle. Marek is thrust into the alien world of the manor, stripped of his past and forced to adapt to new rules. Jude, relieved of his paternal burden, is left to wander, his identity further eroded. The exchange exposes the arbitrary nature of power and the ease with which the weak are traded and discarded by those above.

Drought and Famine Descend

A relentless drought devastates Lapvona, turning the land to dust and driving the villagers to desperation. Hunger and thirst strip away the veneer of civility, revealing the raw struggle for survival. Jude, now alone, clings to his lambs until starvation forces him to acts of madness and cannibalism. The villagers, abandoned by their lord and priest, turn on each other, their faith tested and found wanting. The manor, sustained by hidden reservoirs, becomes a symbol of obscene abundance amid widespread suffering. The drought is both a natural disaster and a metaphor for spiritual desolation, laying bare the inequities and moral failures of Lapvona's society.

The Manor's False Paradise

In the manor, Marek is pampered and fattened, his suffering transformed into entertainment for Villiam and his court. The servants, especially Lispeth, resent and pity him, seeing in Marek a grotesque reflection of their own powerlessness. Villiam's appetite for diversion is insatiable, his cruelty masked by humor and ritual. Marek, torn between guilt and pleasure, loses touch with his former self, becoming complicit in the very system that once oppressed him. The manor's abundance is revealed as a fragile illusion, sustained by exploitation and denial. The contrast between the suffering village and the decadent manor underscores the moral bankruptcy at the heart of Lapvona.

Cannibal Hunger

As famine deepens, Jude and Ina are driven to cannibalism, consuming the bodies of the dead to survive. The act is both horrifying and strangely intimate, a final collapse of the barriers between self and other, human and animal. The village's collective trauma is mirrored in these acts of consumption, as hunger overrides all other considerations. The return of Agata, Marek's mother, signals a turning point, as old secrets and new hungers converge. The boundaries of kinship, morality, and identity are blurred, setting the stage for a reckoning that will reshape Lapvona's fate.

The Nun Returns

Agata, long thought dead, escapes the abbey and returns to Lapvona, her presence both a miracle and a threat. Her silence and pregnancy become the focus of the village's hopes and fears, as rumors of a virgin birth spread. Villiam, ever opportunistic, claims Agata as his bride, seeking to harness the power of myth for his own gain. Marek, recognizing his mother but unable to reclaim her, is consumed by jealousy and longing. The village, desperate for meaning after so much loss, invests Agata's child with messianic significance, setting the stage for a spectacle that will test the limits of faith and authority.

The Wedding of Red

Villiam's marriage to Agata is orchestrated as a grand public event, with the entire village compelled to participate in rituals of fertility and devotion. The color red, symbolizing both blood and nobility, saturates the ceremony, masking the violence and coercion at its heart. Agata's pregnancy is treated as a divine sign, her body a vessel for the community's hopes and anxieties. Marek, excluded and enraged, lashes out, his actions echoing the violence that has always simmered beneath Lapvona's surface. The wedding is both a celebration and a warning, a reminder that power is maintained through spectacle and sacrifice.

The Virgin's Child

Agata gives birth to a child proclaimed as the Christ, but the miracle is hollow. The baby becomes an object of veneration and control, its fate determined by the ambitions and fears of those around it. Ina, restored to youth and vigor, assumes the role of caretaker, while Marek and Jude are left adrift, their identities shattered by loss and betrayal. The village, having survived famine and violence, is eager to believe in redemption, but the promise of salvation is tainted by the memory of suffering and the persistence of injustice. The birth of the child is both an ending and a beginning, a moment of hope shadowed by doubt.

The Collapse of Order

The deaths of Villiam, Lispeth, and Father Barnabas mark the end of Lapvona's old order. Poison, suicide, and despair claim those who once wielded power, leaving a vacuum that cannot be easily filled. Marek, now lord in name, finds that authority brings only emptiness and anxiety. The villagers, freed from the church's control, drift into a new, uncertain existence, their faith in institutions irreparably damaged. The collapse of order is both a liberation and a loss, as the structures that once provided meaning and stability are revealed as hollow and corrupt.

The Lord's Poisoned End

Villiam's demise, brought about by poison and the unraveling of his own schemes, is both justice and tragedy. His death exposes the fragility of power and the inevitability of change. The manor, once a symbol of invincibility, becomes a mausoleum, its rituals and hierarchies rendered meaningless. The villagers, witnessing the fall of their lord, are left to navigate a world without clear leaders or certainties. The end of Villiam's reign is both a reckoning and an opportunity, a moment when the possibility of renewal is shadowed by the weight of the past.

The New Lord's Emptiness

As the new lord of Lapvona, Marek is confronted by the hollowness of authority. Surrounded by reminders of loss and failure, he struggles to find purpose or connection. Jude, now a broken man, rejects Marek's attempts at reconciliation, preferring the company of animals to that of his son. The manor's wealth and comfort offer no solace, and Marek's efforts to restore what was lost only deepen his sense of isolation. The village, too, is adrift, its people uncertain how to rebuild in the absence of faith and leadership. The promise of the Christ child is overshadowed by the reality of human frailty and the persistence of suffering.

The Christ Child's Fate

The story ends with Marek, holding the Christ child, climbing the mountain where so much blood has been spilled. The baby, innocent and smiling, is both a symbol of hope and a reminder of the cycle of violence that has defined Lapvona. Marek, shaped by loss and longing, contemplates the possibility of ending the cycle by sacrificing the child, seeking redemption or release. The fate of the Christ child is left unresolved, a question mark at the end of a story where faith, power, and suffering are inextricably linked. The village, forever changed, stands on the threshold of a new era, its future uncertain but its wounds indelible.

Characters

Marek

Marek is the deformed, sensitive son of Jude and Agata, though his true parentage is shrouded in violence and secrecy. Raised in isolation and abuse, Marek internalizes suffering as virtue, seeking punishment as a form of love. His longing for connection drives him to acts of compassion and violence alike, culminating in the accidental killing of Jacob. Marek's journey from outcast to lord is marked by guilt, envy, and a desperate search for meaning. His relationships—with Jude, Ina, Agata, and Villiam—are fraught with longing and disappointment. Marek embodies the psychological scars of generational trauma, his development stunted by neglect and cruelty, yet he remains a vessel for the village's hopes and anxieties.

Jude

Jude is a lamb herder consumed by grief, bitterness, and religious fervor. His love for Marek is expressed through violence and deprivation, a twisted attempt to mold his son into a worthy soul. Jude's identity is rooted in suffering and self-denial, his worldview shaped by loss—of parents, of Agata, of his own sense of worth. As the story unfolds, Jude's rigidity gives way to madness and despair, culminating in acts of cannibalism and self-exile. His inability to adapt or forgive leaves him isolated, a relic of a world that can no longer sustain him. Jude's psychological complexity lies in his simultaneous need for control and his profound helplessness.

Agata

Agata, Marek's mother, is a figure of trauma and endurance. Mutilated and exiled as a child, she survives by suppressing her voice and desires, becoming a vessel for others' needs. Her return to Lapvona as a mute, pregnant nun transforms her into an object of veneration and control, her body politicized and mythologized. Agata's relationship with Marek is fraught with ambivalence—she is both mother and stranger, protector and betrayer. Her silence is both a wound and a shield, allowing her to endure in a world that seeks to possess and define her. Agata's development is marked by resignation and a fierce, if hidden, will to survive.

Ina

Ina is Lapvona's enigmatic wet nurse, a survivor of plague and abandonment who becomes the village's source of nourishment and wisdom. Her blindness heightens her intuition, allowing her to navigate the world through sound, touch, and the guidance of birds. Ina's milk and medicines sustain generations, but her otherness makes her both revered and feared. She is a mother to many, including Marek, offering comfort and knowledge in a world defined by loss. Ina's psychological resilience is matched by her adaptability, as she reinvents herself in response to changing circumstances. Her eventual restoration of sight and youth symbolizes the possibility of renewal amid decay.

Villiam

Villiam is Lapvona's lord, a man insulated from suffering by wealth and privilege. His appetite for diversion is matched only by his indifference to the suffering of his subjects. Villiam's rule is maintained through spectacle, manipulation, and the calculated use of violence. He is both childlike and cruel, seeking entertainment in the pain of others. His adoption of Marek and marriage to Agata are acts of whimsy and self-interest, revealing the arbitrary nature of authority. Villiam's psychological shallowness is both a defense and a weakness, leaving him vulnerable to the very forces he seeks to control.

Father Barnabas

Father Barnabas is the village priest, a man whose faith is a tool for social control rather than spiritual guidance. He serves as Villiam's informant, reporting on the villagers' moods and ensuring compliance through fear and ritual. Barnabas is a charlatan, more interested in maintaining his own position than in the well-being of his flock. His complicity in the village's suffering is masked by pious language and empty gestures. As the old order collapses, Barnabas is consumed by paranoia and guilt, his authority revealed as hollow. His psychological profile is one of self-preservation and moral cowardice.

Lispeth

Lispeth, once Jacob's attendant, becomes Marek's servant after the exchange. Her relationship with Marek is defined by pity, disgust, and suppressed grief for Jacob. Lispeth's servitude is both a source of pride and a burden, her identity shaped by the whims of those above her. She is a silent witness to the manor's decadence and cruelty, her own desires and sorrows subsumed by duty. Lispeth's psychological complexity lies in her ability to endure and adapt, even as she harbors a quiet rage against the injustices she cannot change.

Jacob

Jacob, Villiam's son, is the embodiment of privilege—handsome, strong, and entitled. His friendship with Marek is marked by condescension and manipulation, a dynamic that ultimately leads to his death. Jacob's casual cruelty and obliviousness to suffering make him both a symbol and a casualty of the world his father has created. His death is a turning point, exposing the fragility of privilege and the dangers of unchecked resentment. Jacob's psychological development is cut short, his potential for growth and change unrealized.

Grigor

Grigor is an old villager whose life is defined by the loss of his grandchildren and a growing distrust of authority. His skepticism and anger set him apart from his neighbors, who prefer denial and compliance. Grigor's journey is one of reluctant awakening, as he confronts the lies and injustices that underpin Lapvona's order. His relationship with Ina offers a glimpse of healing and connection, but he remains marked by the scars of the past. Grigor's psychological arc is one of grief, resistance, and the search for meaning in a world that offers little comfort.

The Christ Child

The child born to Agata is proclaimed as the new Christ, a figure onto whom the village projects its longing for redemption. The baby is both innocent and burdened, its fate determined by the ambitions and fears of those around it. The Christ child's presence is a catalyst for change, exposing the limits of faith and the persistence of suffering. As an object of veneration and control, the child embodies the paradoxes at the heart of Lapvona—a world where hope and despair, innocence and violence, are inseparable.

Plot Devices

Cycles of Violence and Sacrifice

The narrative is structured around recurring cycles of violence, sacrifice, and retribution. From the bandits' attack to the killing of Jacob, from famine to cannibalism, each act of brutality begets another, binding characters in a web of guilt and longing. Sacrifice—whether of lambs, children, or dignity—is both a means of survival and a tool of control. The story uses these cycles to explore the ways in which trauma is inherited and perpetuated, and how attempts at redemption are often co-opted by those in power.

Power, Ritual, and Spectacle

The rulers of Lapvona—Villiam and Father Barnabas—use ritual, spectacle, and myth to legitimize their authority and distract from their failures. Public executions, weddings, and religious ceremonies are orchestrated to reinforce social hierarchies and suppress dissent. The manipulation of faith and superstition is a key plot device, with the promise of miracles and the threat of damnation used to control the populace. The narrative structure mirrors this performative aspect, with events unfolding as a series of staged acts, each revealing the emptiness at the heart of power.

Foreshadowing and Symbolism

The novel employs foreshadowing through natural phenomena—drought, storms, the return of birds—as well as through recurring symbols such as blood, red hair, and the lambs. These elements signal shifts in fortune and the approach of catastrophe or renewal. The use of mirrors, or the lack thereof, underscores themes of identity and self-perception. The Christ child, both a literal and symbolic figure, serves as a focal point for the village's hopes and fears, embodying the tension between salvation and destruction.

Shifting Perspectives and Unreliable Narration

The story is told through the eyes of various characters, each with their own biases, wounds, and limitations. This shifting perspective creates a sense of ambiguity and unreliability, as truths are revealed to be partial or self-serving. The use of internal monologue and psychological detail deepens the reader's understanding of each character's motivations, while also highlighting the impossibility of objective truth in a world defined by suffering and power.

Analysis

Lapvona is a dark, allegorical exploration of power, faith, and the human capacity for cruelty and endurance. Set in a medieval village beset by violence, famine, and superstition, the novel interrogates the ways in which suffering is both inflicted and sanctified by those in authority. Through its cast of damaged, yearning characters, the story exposes the emptiness of rituals and the dangers of blind obedience, while also acknowledging the deep human need for connection and meaning. The cycles of violence and sacrifice that define Lapvona are both a reflection of historical realities and a commentary on contemporary anxieties—about inequality, the manipulation of truth, and the search for redemption in a broken world. The novel's refusal to offer easy answers or tidy resolutions is its greatest strength, forcing readers to confront the ambiguities of morality and the persistence of hope amid despair. In the end, Lapvona suggests that salvation, if it exists, is not found in miracles or authority, but in the fragile, imperfect bonds between people—and in the courage to see the world as it is, rather than as we wish it to be.

Last updated:

Review Summary

Lapvona receives mixed reviews, with an average rating of 3.54/5. Readers find it grotesque, disturbing, and thought-provoking. Many praise Moshfegh's unique style and exploration of themes like religion, power, and human nature. However, some criticize its excessive vulgarity and lack of deeper meaning. The medieval setting and dark, fairy-tale-like atmosphere are noted. While some consider it Moshfegh's best work, others find it disappointing. The book's polarizing nature is evident, with readers either captivated or repulsed by its content.