Plot Summary

Vegetable Wheel and Fate

Sixteen-year-old Griet's life in Delft is upended when her father, a tile painter, is blinded in a kiln accident, plunging the family into poverty. Griet's mother arranges for her to work as a maid in the household of the renowned painter Johannes Vermeer. Griet's meticulous nature is revealed in the way she arranges vegetables by color, a detail that catches Vermeer's attention during their first meeting. This moment foreshadows the unique connection that will develop between Griet and the painter, as well as the new world she is about to enter—a world of art, color, and complex social hierarchies. Griet's journey begins not by her own choice, but out of necessity, setting the stage for her transformation and the tensions that will shape her life.

Into the Painter's World

Griet is thrust into the Vermeer household, a bustling, Catholic home filled with children, paintings, and strict routines. She must quickly learn to navigate the complex relationships between the family members, the other servant Tanneke, and the formidable matriarch Maria Thins. Griet's Protestant background makes her an outsider, and she is acutely aware of the differences in faith and custom. Her primary duty is to clean Vermeer's studio without disturbing the careful arrangement of objects—a task that requires both precision and intuition. Griet's sensitivity to order and detail earns her a place of trust, but also draws her deeper into the private world of the artist, where observation and silence are both a shield and a burden.

The Vermeer Household

Life in the Vermeer house is a constant negotiation of power and affection. Griet faces hostility from Catharina, Vermeer's pregnant and volatile wife, and the mischievous daughter Cornelia, who senses Griet's vulnerability. Tanneke, the senior maid, is both a rival and a reluctant mentor, while Maria Thins, the true authority, watches Griet with a shrewd, calculating eye. Griet's position is precarious; she must work hard to avoid mistakes and navigate the shifting moods of the household. The children, especially Cornelia, test her boundaries, and Griet learns that survival depends on discretion, adaptability, and the ability to read the unspoken tensions that simmer beneath the surface.

Studio Secrets and Shadows

Griet's duties in the studio become a sanctuary from the chaos of the household. She develops a method for cleaning without disturbing the arrangement of objects, using her hands and body as measuring tools. Vermeer notices her sensitivity to color and composition, and gradually involves her in the preparation of his materials—grinding pigments, mixing paints, and eventually assisting with the setup of his scenes. This secret collaboration draws Griet into the intimate process of creation, blurring the lines between servant and muse. The studio becomes a space of silent communication, where Griet's understanding of art deepens, and her connection to Vermeer intensifies, even as it remains unspoken and fraught with danger.

The Patron's Gaze

The Vermeer family's financial survival depends on the patronage of the wealthy and predatory van Ruijven. His gaze lingers on Griet, and rumors swirl about his intentions. Van Ruijven's history with maids and his demand for paintings featuring young women create a climate of fear and suspicion. Griet becomes the object of his attention, and the household is thrown into turmoil as Maria Thins and Vermeer maneuver to protect her without offending their benefactor. The threat of exploitation hangs over Griet, highlighting the vulnerability of women and servants in a world where power is wielded through both money and desire.

The Camera Obscura

Vermeer introduces Griet to the camera obscura, a device that projects images and alters perception. Through this experience, Griet learns to see the world as an artist does—recognizing the complexity of color, light, and form. The camera obscura becomes a symbol of the transformative power of art, as well as the distance between reality and representation. Griet's education in the language of painting deepens her bond with Vermeer, but also isolates her further from the rest of the household, who cannot understand the nature of their collaboration. The act of seeing becomes both a privilege and a burden, as Griet is drawn ever closer to the heart of Vermeer's creative vision.

Plague and Loss

When plague strikes Griet's family's neighborhood, she is forbidden from visiting them, and her sense of isolation grows. News arrives that her beloved younger sister Agnes has died, a loss that devastates Griet and underscores the fragility of life. The quarantine and subsequent grief mark a turning point, hardening Griet's resolve and deepening her dependence on the Vermeer household. The episode also exposes the limits of compassion and the harsh realities faced by the poor. Griet's mourning is private and largely unacknowledged, further emphasizing her loneliness and the sacrifices demanded by her position.

Finding Her Place

Over time, Griet carves out a place for herself in the Vermeer household. She learns to manage the competing demands of Catharina, Tanneke, and Maria Thins, and to use her skills to gain small advantages. Her relationship with the children, especially the more sympathetic Maertge and Aleydis, becomes a source of comfort. Griet's growing expertise in the studio and her ability to anticipate Vermeer's needs make her indispensable, but also increase the risk of discovery and scandal. She becomes adept at concealing her feelings and intentions, understanding that her survival depends on maintaining a delicate balance between visibility and invisibility.

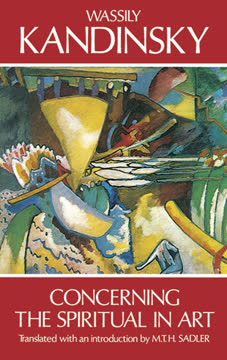

The Language of Color

Griet's apprenticeship in color and light becomes a metaphor for her awakening to the complexities of desire, power, and selfhood. Vermeer teaches her to see the world in new ways, challenging her assumptions and drawing her into the mysteries of artistic creation. Their collaboration is marked by a charged intimacy that is never fully articulated, but is felt in every glance and gesture. Griet's understanding of art becomes inseparable from her understanding of herself, and the risks she takes in the studio mirror the emotional and social risks she faces in the household. The act of seeing—and being seen—becomes both a source of empowerment and vulnerability.

Pieter and the Butcher's Son

Pieter, the butcher's son, begins to court Griet, offering her the promise of security and a future outside the Vermeer household. Griet's parents encourage the match, seeing in Pieter a way to escape poverty and dependence. Griet is torn between the stability Pieter represents and the dangerous allure of her life with Vermeer. Her relationship with Pieter is marked by awkwardness and ambivalence; she is unable to give herself fully to him while she remains entangled in the world of the studio. The tension between duty and desire, safety and passion, becomes increasingly acute as Griet approaches adulthood.

The Rumor of a Painting

Rumors spread that Griet is to be painted by Vermeer, possibly alongside van Ruijven. The prospect of being immortalized in a painting is both thrilling and terrifying, as it would expose Griet to public scrutiny and potential ruin. Maria Thins and Vermeer maneuver to protect her, but the power dynamics of patronage and gender leave Griet with little agency. The threat of scandal looms, and Griet is forced to confront the limits of her autonomy. The unfinished painting becomes a site of negotiation, desire, and danger, encapsulating the stakes of Griet's position in the household and in society.

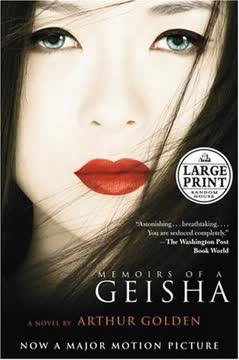

The Pearl Earring Dilemma

Vermeer decides to paint Griet alone, with her head wrapped in blue and yellow cloth and wearing Catharina's pearl earring. The act of piercing her ear and donning the earring becomes a moment of profound transformation and risk. Griet's complicity in the deception, and her willingness to submit to Vermeer's vision, mark the culmination of her journey from servant to muse. The painting is both a work of art and a record of transgression, capturing the tension between innocence and experience, submission and self-assertion. The completion of the painting signals the end of Griet's time in the Vermeer household, as the consequences of her actions come to a head.

Betrayal and Exile

Catharina discovers the painting and the theft of her earrings, leading to a dramatic confrontation in the studio. Griet is accused, but neither Vermeer nor Maria Thins defend her openly. The household's simmering resentments and rivalries erupt, and Griet realizes that she has no place left in the world she helped create. She leaves the house in disgrace, her future uncertain. The moment is both an exile and a liberation, as Griet steps out into the world to choose her own path, no longer defined solely by the needs and desires of others.

Ten Years Later

A decade passes. Griet is now married to Pieter, with children of her own, working in the butcher's stall. She has settled into a life of modest security, but the scars of her past remain. News arrives of Vermeer's death, and Griet is summoned back to the Vermeer household by Tanneke. The house is diminished, burdened by debt and loss. Griet's return is marked by a sense of closure and reckoning, as she confronts the ghosts of her former life and the choices that shaped her destiny.

The Final Gift

In a final act of recognition, Vermeer's will bequeaths Griet the pearl earrings that once symbolized her transformation and her fall. Catharina, embittered but resigned, fulfills her husband's wishes and gives Griet the earrings. Griet, understanding that she cannot keep them, sells the pearls and uses the money to settle the Vermeer family's debt to her husband's butcher shop. The gesture is both practical and symbolic—a way of closing the circle, repaying old debts, and laying the past to rest. Griet's journey ends not with triumph or tragedy, but with a quiet act of self-determination and grace.

Characters

Griet

Griet is the protagonist, a Protestant maid whose acute sensitivity to color, order, and nuance draws her into the world of art and desire. Her psychological journey is one of awakening—first to the beauty and complexity of the world, then to the dangers and limitations imposed by class, gender, and power. Griet's relationships—with her family, the Vermeers, Pieter, and Vermeer himself—are marked by longing, restraint, and the constant negotiation of boundaries. She is both a victim and an agent, her silence and compliance masking a fierce inner life. Griet's development is shaped by loss, love, and the struggle to define herself in a world that seeks to use and contain her.

Johannes Vermeer

Vermeer is the master painter whose artistic genius is matched by his emotional reserve. He is both mentor and enigma to Griet, recognizing her talent and drawing her into his creative process. Vermeer's world is one of order, light, and vision, but he is often oblivious to the consequences of his actions for those around him. His relationship with Griet is charged with unspoken desire and mutual understanding, yet he remains ultimately inaccessible—more committed to his art than to any individual. Vermeer's psychological complexity lies in his ability to see and create beauty, even as he fails to protect or fully acknowledge those who make his work possible.

Catharina Vermeer

Catharina is Vermeer's wife, perpetually pregnant and anxious about her husband's affections and the family's finances. She is both a rival and a victim, her authority undermined by her mother Maria Thins and her husband's indifference. Catharina's relationship with Griet is marked by suspicion, resentment, and occasional flashes of vulnerability. Her psychological turmoil is rooted in her fear of displacement—by Griet, by art, by poverty. Catharina's final act of giving Griet the earrings is both an admission of defeat and a gesture of reluctant closure.

Maria Thins

Maria Thins is the true matriarch of the Vermeer household, wielding authority through wealth, experience, and cunning. She recognizes Griet's value and protects her when it serves the family's interests, but is ultimately loyal to her own blood. Maria Thins is a survivor, adept at managing conflict and maintaining appearances. Her relationship with Griet is complex—part mentor, part adversary, always transactional. She embodies the compromises and calculations required to survive in a world of shifting fortunes.

Tanneke

Tanneke is the senior maid, whose long service in the Vermeer household gives her a sense of ownership and entitlement. She is both threatened by and protective of Griet, her moods swinging between camaraderie and hostility. Tanneke's loyalty to Maria Thins and the family is genuine, but her resentment of Griet's special status fuels conflict. Her psychological landscape is shaped by the precariousness of servant life, the need for recognition, and the pain of being overlooked.

Cornelia

Cornelia, one of the Vermeer daughters, is a child who senses and exploits the vulnerabilities of others. She is both a source of comic relief and a catalyst for trouble, her actions often motivated by jealousy and a desire for attention. Cornelia's relationship with Griet is antagonistic, and her mischief has real consequences, contributing to Griet's downfall. She represents the dangers of unchecked power and the cruelty that can arise in hierarchical households.

Pieter

Pieter is the butcher's son who courts and eventually marries Griet. He offers her security, stability, and a way out of servitude, but is unable to fully understand or satisfy her deeper longings. Pieter's love is sincere, but his world is one of flesh and blood, not art and vision. His psychological role is to anchor Griet in reality, to remind her of the choices and compromises required for survival. Pieter's patience and decency are both a comfort and a constraint.

Van Ruijven

Van Ruijven is Vermeer's patron, whose wealth and influence make him both benefactor and threat. His interest in Griet is sexual and possessive, and his demands drive much of the plot's tension. Van Ruijven's psychological makeup is that of entitlement—he expects to get what he wants, regardless of the cost to others. He embodies the dangers faced by women and servants in a patriarchal society, and his presence is a constant reminder of the limits of agency and safety.

Agnes

Agnes is Griet's younger sister, whose death from plague marks a turning point in Griet's life. She represents innocence, familial love, and the pain of loss. Agnes's absence haunts Griet, deepening her sense of isolation and her longing for connection. Her memory is a source of both sorrow and strength, shaping Griet's choices and her understanding of what is at stake.

Maertge

Maertge is one of the Vermeer daughters who forms a bond with Griet. She is more sympathetic and less volatile than her siblings, offering Griet moments of kindness and understanding. Maertge's development mirrors Griet's in some ways, as she grows into her own role within the family. Her later visits to Griet after Griet's exile suggest the possibility of forgiveness and continuity.

Plot Devices

The Studio as Sanctuary and Stage

The Vermeer studio is a liminal space where Griet's identity is both concealed and revealed. It is a place of order, beauty, and creation, but also of secrecy, risk, and transgression. The studio's rules—objects must not be moved, light must be controlled—mirror the constraints placed on Griet's life, even as they offer her a rare sense of agency. The studio is where Griet and Vermeer's relationship is forged, and where the boundaries between servant and muse, art and life, are most porous.

The Pearl Earring

The pearl earring is the central plot device, representing the intersection of art, sexuality, and social transgression. To wear the earring, Griet must pierce her ear, an act that is both literal and symbolic—a crossing of boundaries, a submission to the demands of art and the artist. The earring is also a source of scandal and betrayal, its theft and use precipitating Griet's exile. In the end, the earring becomes a token of memory and closure, its value both material and emotional.

Foreshadowing and Mirrors

The novel uses foreshadowing—such as Griet's arrangement of vegetables and her early encounters with Vermeer—to signal the trajectory of her journey. Mirrors and reflections recur as motifs, highlighting the themes of perception, self-knowledge, and the gap between appearance and reality. Griet's ability to see and be seen is both her gift and her undoing, and the act of looking becomes a central metaphor for the risks and rewards of engagement with the world.

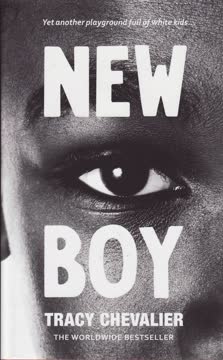

Social Hierarchy and Gender

The plot is driven by the rigid hierarchies of 17th-century Dutch society, where servants are vulnerable, women are commodities, and power is wielded through patronage and marriage. Griet's navigation of these structures—her silence, her compliance, her small acts of rebellion—reflects the limited agency available to her. The threat of sexual exploitation, the pressure to marry, and the constant negotiation of status are ever-present, shaping the novel's conflicts and resolutions.

The Unfinished Painting

The painting of Griet is both a culmination and a rupture. It immortalizes her, but also marks the end of her relationship with Vermeer and her place in his world. The act of painting is depicted as both an act of love and a form of violence, requiring sacrifice and leaving wounds. The painting's completion signals Griet's exile, and her inability to ever truly possess or be possessed by the world of art.

Analysis

"Girl with a Pearl Earring" is a nuanced exploration of the intersections between art, gender, and class. Through Griet's eyes, Tracy Chevalier examines the ways in which beauty is both created and consumed, and the price paid by those who serve as its vessels. The novel interrogates the limits of

Last updated:

FAQ

Synopsis & Basic Details

What is Girl with a Pearl Earring about?

- A Maid's Artistic Awakening: Girl with a Pearl Earring follows Griet, a sixteen-year-old Protestant girl in 17th-century Delft, who becomes a maid in the chaotic Catholic household of the enigmatic painter Johannes Vermeer after her tile-painter father is blinded.

- Unspoken Connection & Artistic Muse: Griet's keen eye for color and order draws Vermeer's attention, leading to a secret apprenticeship where she grinds pigments and assists in his studio, developing a profound, unspoken bond with the artist that transcends their social divide.

- Navigating Perilous Worlds: As Griet becomes increasingly entangled in Vermeer's artistic world, she must navigate the jealousies of his wife Catharina, the manipulations of his patron van Ruijven, and the expectations of her own family and a suitor, Pieter, all while struggling to maintain her identity and virtue.

Why should I read Girl with a Pearl Earring?

- Immersive Historical Experience: Dive into the meticulously researched world of 17th-century Delft, experiencing its sights, sounds, and social customs through Griet's vivid sensory perceptions, offering a rich historical tapestry.

- Profound Psychological Depth: Explore the intricate inner life of a young woman caught between duty and desire, class and artistic passion, as she grapples with her identity and the unspoken complexities of human connection.

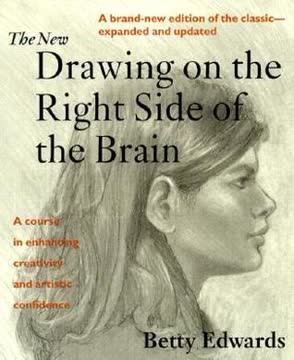

- Artistic Process Revealed: Gain a unique insight into the creation of art, from the grinding of pigments to the play of light, making the famous painting come alive and deepening appreciation for the artist's craft and the muse behind it.

What is the background of Girl with a Pearl Earring?

- Inspired by a Masterpiece: The novel is a fictionalized account inspired by Johannes Vermeer's iconic painting, "Girl with a Pearl Earring," imagining the circumstances and the model behind the mysterious portrait.

- 17th-Century Dutch Golden Age: Set in Delft during the Dutch Golden Age, the story immerses readers in a period of immense artistic, scientific, and economic prosperity, contrasting the opulence of the art world with the harsh realities of servant life and religious tensions between Protestants and Catholics.

- Vermeer's Enigmatic Life: Tracy Chevalier builds upon the sparse historical facts known about Vermeer's life—his large family, his financial struggles, his slow painting pace, and his patrons—to craft a compelling narrative that fills in the blanks of his personal and artistic world.

What are the most memorable quotes in Girl with a Pearl Earring?

- "The colors fight when they are side by side, sir.": This early observation by Griet about vegetables, made to Vermeer, immediately establishes her unique visual sensitivity and foreshadows her deep understanding of color and composition, a key element in her connection with the painter.

- "He sees things in a way that others did not, so that a city I had lived in all my life seemed a different place, so that a woman became beautiful with the light on her face.": Griet's profound realization about Vermeer's artistic vision highlights his transformative power to reveal hidden beauty and meaning in the ordinary, and her own growing perception.

- "You must take care then — Take care to remain yourself.": Van Leeuwenhoek's warning to Griet underscores the central theme of identity and the danger of being consumed by another's artistic vision or desires, urging her to resist becoming merely a subject or an object.

What writing style, narrative choices, and literary techniques does Tracy Chevalier use?

- First-Person, Sensory-Rich Narration: Chevalier employs a first-person perspective through Griet, immersing the reader in her immediate, sensory experiences of 17th-century Delft, from the smell of linseed oil to the texture of fabrics, making the historical setting palpable.

- Sparse Dialogue & Internal Monologue: The narrative relies heavily on Griet's internal thoughts and observations, with dialogue often brief and understated, emphasizing the unspoken tensions and emotional restraint characteristic of the period and Griet's character.

- Symbolism and Visual Imagery: The novel is rich with symbolism, particularly involving color, light, and everyday objects (like Griet's cap or the pearl earring), which serve as metaphors for character states, social hierarchies, and the transformative power of art, mirroring Vermeer's own visual language.

Hidden Details & Subtle Connections

What are some minor details that add significant meaning?

- Griet's Cap as a Shield: Beyond modesty, Griet's cap is a deliberate choice to hide her true self and emotions, especially her hair, which she considers untamed and revealing. "I favored a white cap that folded in a wide brim around my face, covering my hair completely and hanging down in points on each side of my face so that from the side my expression was hidden."

- The Broken Tile's Prophetic Symbolism: Cornelia's act of breaking Griet's cherished tile, separating the boy and girl figures, subtly foreshadows the fragmentation of Griet's own family and her eventual emotional distance from them, particularly Frans. "It had been broken so that the girl and boy were separated from each other, the boy now looking behind him at nothing, the girl all alone, her face hidden by her cap."

- Vermeer's "Clean" Appearance: His initial "clean appearance" without a beard or moustache contrasts sharply with the messy, demanding reality of his large family and the blood-stained world of Pieter, subtly highlighting his detachment from domestic chaos and his focus on an idealized artistic vision. "He had no beard or moustache, and I was glad, for it gave him a clean appearance."

What are some subtle foreshadowing and callbacks?

- The Falling Knife's Omen: Catharina's accidental knocking of Griet's knife to the floor during their first meeting subtly foreshadows the domestic chaos and potential for violence that Griet will encounter in the Vermeer household, and Catharina's own volatile nature. "As the woman turned to look at the man, a fold of her mantle caught the handle of the knife I had been using, knocking it off the table so that it spun across the floor."

- Camera Obscura's Inverted Reality: The camera obscura's projection of an "upside down, and left and right reversed" image foreshadows how Griet's perception of her world will be inverted and challenged by her experiences in the studio, blurring social norms and her understanding of reality. "Yes, the image is projected upside down, and left and right are reversed."

- Pieter's Bloody Hands: Griet's repeated observation of Pieter's blood-stained hands, initially a source of discomfort, subtly foreshadows her eventual acceptance of the practical, visceral realities of her life with him, contrasting with the clean, idealized world of art. "The creases between his nails and his fingers were filled with blood. I expect I will have to get used to that sight, I thought."

What are some unexpected character connections?

- Maria Thins' Past as a Victim: The revelation that Maria Thins' husband (Catharina's father) used to beat her, and that Tanneke bravely intervened when Willem beat Catharina, adds a layer of unexpected vulnerability and resilience to the formidable matriarch. "He used to beat her." This explains her pragmatism and protective instincts.

- Frans's Shared Temptation: Griet's brother Frans, initially a symbol of her lost family innocence, reveals his own vulnerability to temptation and "punishment" for showing interest in his master's wife, creating an unexpected parallel with Griet's own precarious situation with Vermeer and van Ruijven. "It was she who started it... But when I showed mine she told her husband."

- Tanneke's Hidden Bravery: Despite her often surly and envious nature towards Griet, Tanneke's past act of defending Catharina from her violent brother Willem reveals a deep, unexpected loyalty and courage beneath her gruff exterior. "Tanneke got in between them to protect her. Even thumped him soundly."

Who are the most significant supporting characters?

- Maria Thins: The Pragmatic Strategist: Beyond her role as matriarch, Maria Thins is the true architect of the Vermeer household's survival, shrewdly managing finances, protecting Vermeer's artistic output, and subtly manipulating social dynamics to her family's advantage, including Griet's role. "She knew that he had been very busy at the Guild that winter... Perhaps she had decided to wait and see if things would change in the summer."

- Van Leeuwenhoek: The Voice of Reason and Warning: As Vermeer's friend and a scientific observer, van Leeuwenhoek serves as a detached, philosophical commentator, offering Griet crucial warnings about Vermeer's artistic single-mindedness and the dangers of losing herself in his world. "He thinks only of himself and his work, not of you. You must take care then — Take care to remain yourself."

- Cornelia: The Catalyst of Conflict: More than just a mischievous child, Cornelia acts as a persistent antagonist and unwitting catalyst, her deliberate acts of malice (breaking the tile, the madder incident, the comb switch) consistently pushing Griet into difficult situations and exposing her secrets, ultimately leading to the climax. "She will do this until she drives me away, I thought."

Psychological, Emotional, & Relational Analysis

What are some unspoken motivations of the characters?

- Vermeer's Artistic Imperative: His primary motivation is the pursuit of artistic perfection, often at the expense of personal relationships or the feelings of those around him. His "nervousness" when asking Griet to wear the earring isn't about her comfort, but the painting's completion. "I know the painting will be complete."

- Catharina's Quest for Validation: Her constant pregnancies and desire for a large household, despite financial strain, are driven by an unspoken need for validation and a sense of purpose, especially as she feels overlooked by her artist husband. "Sometimes I think she's filling the house with children because she can't fill it with servants as she'd like."

- Maria Thins' Calculated Protection: Her protection of Griet and her subtle support of Vermeer's artistic process are not purely altruistic, but motivated by a pragmatic understanding that Vermeer's art is the family's only real asset and Griet is essential to its production. "You help him to paint faster, girl, and you'll keep your place here."

What psychological complexities do the characters exhibit?

- Griet's Internalized Silence and Observation: Griet's psychological complexity lies in her profound inner world, which she carefully guards through silence and keen observation, a coping mechanism developed from her subordinate position and Protestant upbringing in a Catholic household. "I did not often lie. I looked down."

- Vermeer's Detached Artistic Vision: Vermeer exhibits a profound detachment from the emotional consequences of his actions, viewing people and objects primarily as elements within his artistic compositions. His inability to "see" Griet as a person beyond her role as a model highlights this complexity. "He looked at me as if he were not seeing me, but someone else, or something else—as if he were looking at a painting."

- Catharina's Performance of Domesticity: Catharina's psychological state is marked by a performative domesticity, where she strives to embody the role of a wealthy mistress while struggling with insecurity, jealousy, and a sense of powerlessness within her own home. "She wants to hold on to the appearance of motherhood, if not the tasks themselves."

What are the major emotional turning points?

- Agnes's Death and Griet's Hardening: The news of Agnes's death from the plague is a devastating emotional turning point for Griet, deepening her sense of isolation and forcing her to confront the harsh realities of life and loss, hardening her resolve. "There followed a time when everything was dull."

- The Camera Obscura Revelation: Griet's first experience with the camera obscura is an emotional awakening, transforming her perception of light and color and forging a profound, intimate connection with Vermeer's artistic vision, marking her true entry into his world. "I opened my eyes and saw the painting, without the woman in it. 'Oh!'"

- The Piercing of the Ear: This act is a deeply personal and painful emotional climax, symbolizing Griet's ultimate sacrifice and submission to Vermeer's artistic demands, blurring the lines of her identity and virtue. "Just before I fainted I thought, I have always wanted to wear pearls."

How do relationship dynamics evolve?

- Griet and Tanneke: From Rivalry to Grudging Acceptance: Their relationship evolves from initial hostility and Tanneke's envy to a grudging, practical acceptance, especially after Griet's position is solidified by Maria Thins. Tanneke's later acts of petty sabotage show her lingering resentment, but also her inability to truly undermine Griet. "She became much harder with me, though—deliberately difficult rather than unthinkingly so."

- Griet and Her Family: Growing Distance and Misunderstanding: Griet's relationship with her parents and brother Frans becomes increasingly strained and distant as her new life at the Vermeers' transforms her. Her inability to fully share her experiences or be understood by them highlights her growing isolation. "After only a few months I could describe the house in Papists' Corner better than my family's."

- Vermeer and Catharina: A Marriage of Convenience and Artistic Detachment: Their marriage is characterized by a profound emotional distance, with Vermeer prioritizing his art and Catharina seeking validation through children and social status. The final confrontation over the painting reveals the deep chasm between them, with Catharina's rage stemming from years of neglect. "Why,' she asked, 'have you never painted me?'"

Interpretation & Debate

Which parts of the story remain ambiguous or open-ended?

- The True Nature of Griet and Vermeer's Relationship: The novel deliberately leaves the romantic or sexual nature of their bond ambiguous, focusing instead on their intense artistic and intellectual connection. Readers are left to interpret whether Vermeer's interest was purely aesthetic, or if deeper, unspoken feelings existed. "He looked at me as if he were not seeing me, but someone else, or something else—as if he were looking at a painting."

- Vermeer's Final Intentions with the Earrings: While the will bequeaths the pearls to Griet, his exact motivation for this final gift remains open to interpretation. Was it a gesture of love, a recognition of her artistic contribution, a final act of control, or a practical way to settle a debt? "He asked that you have these."

- Griet's Ultimate Sense of Self: Despite her journey of self-discovery and agency, Griet's final decision to sell the pearls and settle into a practical life with Pieter leaves her ultimate sense of fulfillment and identity open to debate. Has she truly "remained herself" as van Leeuwenhoek advised, or has she simply traded one form of servitude for another?

What are some debatable, controversial scenes or moments in Girl with a Pearl Earring?

- Griet's Sexual Encounter with Pieter: The scene where Griet "let him do as he liked" in the alley after Vermeer sees her hair is highly debatable. It can be interpreted as a desperate act of self-punishment, a reclaiming of agency on her own terms, or a pragmatic submission to her inevitable future, rather than an act of desire. "He gave me pain, but when I remembered my hair loose around my shoulders in the studio, I felt something like pleasure too."

- Vermeer's Demand for the Pearl Earring: Vermeer's insistence that Griet pierce her ear to wear Catharina's pearl, knowing the social and personal consequences for Griet, is a controversial act of artistic ruthlessness. It raises questions about the ethics of art and the exploitation of the muse. "I know the painting will be complete."

- Catharina's Attempt to Destroy the Painting: Catharina's violent outburst, attempting to slash the painting with a palette knife, is a controversial moment that highlights the destructive power of jealousy and betrayal. It forces readers to confront the human cost of artistic creation and the emotional toll on those left in its wake. "He caught her by the wrist as she plunged the diamond blade of the knife towards the painting."

Girl with a Pearl Earring Ending Explained: How It Ends & What It Means

- A Practical Rejection of Artistic Allure: Griet ultimately sells the pearl earrings bequeathed to her by Vermeer, using the money to settle the Vermeer family's long-standing debt to Pieter's butcher shop. This act signifies her rejection of the idealized, dangerous world of art and her embrace of a grounded, practical life, prioritizing financial stability over symbolic beauty. "I could not keep them. What would I do with them?"

- Closure and Self-Determination: By settling the debt, Griet achieves a form of closure, severing her final material ties to the Vermeer household and reclaiming agency over her own life and finances. It's a quiet act of self-determination, choosing her own path rather than being defined by the desires of others. "Pieter would be pleased with the rest of the coins, the debt now settled. I would not have cost him anything. A maid came free."

- Lingering Scars and Unspent Wealth: Despite her practical choice, Griet keeps five extra guilders, a secret stash that symbolizes the indelible mark of her past and the hidden depths of her experience that her new life cannot fully erase. The "tiny buds of hard flesh" in her ears, where the pearls once hung, are a physical reminder of her sacrifice and transformation. "I would hide them somewhere that Pieter and my sons would not look, some unexpected place that only I knew of. I would never spend them."

Review Summary

Girl with a Pearl Earring receives mixed reviews. Some praise its vivid historical setting, engaging story, and beautiful prose, while others criticize flat characters and artificial dialogue. Many readers appreciate the artistic aspects and Vermeer's portrayal, but some find the plot slow and predictable. The book explores themes of art, class, and forbidden attraction in 17th-century Delft. While some consider it a captivating historical fiction, others feel it lacks depth and authenticity. Overall, opinions vary widely on the novel's merits and weaknesses.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.