Key Takeaways

1. The Father: A Master of Artifice and Hidden Desires

HE USED HIS SKILLFUL ARTIFICE NOT TO MAKE THINGS, BUT TO MAKE THINGS APPEAR TO BE WHAT THEY WERE NOT.

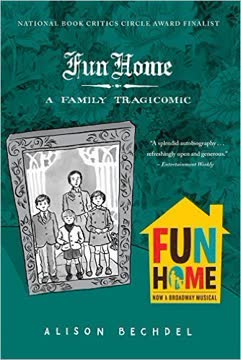

A complex figure. Alison Bechdel's father, Bruce, was a man of many contradictions: a funeral home director, high school English teacher, and obsessive restorer of their Victorian home. He was a "Daedalus of decor," capable of transforming garbage into gold and conjuring period interiors from a paint chip. This meticulous artistry, however, extended beyond aesthetics into his personal life, creating a facade that concealed his true self.

A closeted life. Beneath the surface of his seemingly ideal family man persona, Bruce Bechdel harbored a profound secret: he was a closeted homosexual. This hidden identity manifested in "unwholesome interest in the decorative arts" and illicit affairs with male students and the family babysitter. His passion, in every sense of the word, was channeled into his projects, leaving his family emotionally distant and his true desires unacknowledged.

Human cost. The father's relentless pursuit of aesthetic perfection and his need for concealment came at a significant human cost. He treated his children "like furniture," extensions of his projects, rather than individuals. This indifference to the emotional needs of his family mirrored Daedalus's disregard for the human cost of his labyrinthine creations, trapping his family in a maze of unspoken truths and emotional isolation.

2. The "Fun Home": A Museum of Family Pretense

THAT OUR HOUSE WAS NOT A REAL HOME AT ALL BUT THE SIMULACRUM OF ONE, A MUSEUM.

A gothic mansion. The Bechdel family home, a gothic revival mansion, was meticulously restored by Alison's father, transforming it into a period showplace. This grand, ornate setting, however, served as a physical manifestation of the family's emotional landscape: beautiful on the surface, but filled with hidden passages and a pervasive sense of unreality. The children even called the family funeral parlor the "fun home," a darkly ironic nickname that hinted at the morbid undercurrents of their lives.

A curated existence. The father's "monomaniacal restoration" of the house was an act of constant curation, designed to control appearances and conceal the family's true, unusual nature. The gilt cornices, marble fireplaces, and calf-bound books were "not so much bought as produced from thin air by my father's remarkable legerdemain," reflecting his ability to create illusions. This environment fostered a sense of unreality, where the family lived in "period rooms" that felt more like exhibits than living spaces.

Missing vitality. Despite the elaborate facade, something vital was missing from the home. Alison describes an "elasticity, a margin for error" that was absent, leading to constant tension. The house, with its "meticulous, period mirrors, distracting bronzes, multiple doorways," was designed to conceal the father's "fully developed self-loathing," making it a labyrinth where visitors and even family members could get lost, both physically and emotionally.

3. Literature: A Shared Language in an Emotionally Distant Family

APART FROM ASSIGNED STINTS DUSTING CASKETS AT THE FAMILY-OWNED “FUN HOME,” AS ALISON AND HER BROTHERS CALL IT, THE RELATIONSHIP ACHIEVES ITS MOST INTIMATE EXPRESSION THROUGH THE SHARED CODE OF BOOKS.

A bond through books. In a family where physical affection was rare and emotional expression stifled, literature became the primary medium for connection between Alison and her father. Their shared love for books, particularly classic authors like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Marcel Proust, provided a "shared code" through which they could communicate, albeit indirectly, about life's complexities and their own inner worlds.

Literary parallels. Alison frequently uses literary allusions to understand her parents and their marriage. She compares her father to Fitzgerald's Gatsby, fueled by "the colossal vitality of his illusion," and her mother to a Henry James heroine, "ensnared by degenerate continental forces." These literary frameworks allowed Alison to process the "arctic climate of our family" and the unspoken truths that defined their relationships, making her parents "most real to me in fictional terms."

A double-edged sword. While books offered a unique intimacy, they also served as a tool for the father's concealment and manipulation. His passion for Fitzgerald's stories, "their inextricability from Fitzgerald's life," resonated with his own desire to blur the lines between fiction and reality. He used literature to engage with his students, sometimes with "sexual promise," and even offered Alison Camus's A Happy Death before his own ambiguous demise, hinting at his internal struggles through literary references.

4. Alison's Awakening: A Parallel Journey of Self-Discovery

MY HOMOSEXUALITY REMAINED AT THAT POINT PURELY THEORETICAL, AN UNTESTED HYPOTHESIS.

A bookish coming out. Alison's realization of her own lesbian identity at nineteen was deeply intertwined with her "bookish upbringing." She devoured books on homosexuality, moving from dictionary definitions to a "four-foot trove in the stacks" of the library. This intellectual exploration, rather than personal experience, formed the foundation of her self-discovery, leading her to a "public declaration" at a "Gay Union" meeting.

The "catastrophe" of truth. Her decision to tell her parents about her homosexuality, via a letter, was met with a "staggering blow" from her mother, who revealed her father's own secret affairs with men. This "doleful coming-out party" upstaged Alison's own drama, pulling her back into her parents' orbit and leading her to assume a "cause-and-effect relationship" between her revelation and her father's subsequent death.

Emancipation and entanglement. Alison initially imagined her confession as an "emancipation from my parents," a break from their secrets. However, it instead entangled her further in their complex lives, forcing her to confront the "dark secret" that had permeated her childhood. Her journey of self-acceptance became inextricably linked with unraveling her father's hidden life, transforming her personal narrative into a "tragicomic" family tale.

5. The Ambiguous Death: A Final Act of Concealment

HIS DEATH WAS QUITE POSSIBLY HIS CONSUMMATE ARTIFICE, HIS MASTERSTROKE.

An "accident" or suicide? Alison's father died after being struck by a truck, an event officially ruled an accident. However, Alison strongly suspects it was suicide, a "consummate artifice" designed to maintain his carefully constructed facade even in death. Several "suggestive circumstances" fueled her suspicion, including his wife asking for a divorce two weeks prior and his conspicuous reading of Camus's A Happy Death.

Clues and contradictions. The father's actions leading up to his death were riddled with clues and contradictions. He left a highlighted passage in Camus's novel, a "fitting epitaph for my parents' marriage," yet also made a marginal notation about spotting a "rufous-sided towhee" just days before. This blend of despair and mundane observation made his intentions inscrutable, leaving Alison to grapple with the "complexity of loss itself."

The undertaker's paradox. The father's profession as an undertaker added another layer of irony to his death. Alison pondered "Who embalms the undertaker when he dies?" likening it to Russell's Paradox, an unsolvable conundrum. His death, rather than bringing clarity, only made his life "more incomprehensible," leaving his family with an "absence of grief" and a profound sense of irritation at the unresolved mystery.

6. Inversion and Reflection: Father and Daughter's Queer Identities

NOT ONLY WERE WE INVERTS. WE WERE INVERSIONS OF ONE ANOTHER.

A shared "bent." Alison observes a "decided bent" for gardening in her father, which she connects to his "other, more deeply disturbing bent" for homosexuality. She questions, "What kind of man but a sissy could possibly love flowers this ardently?" This early perception of her father's "sissy" nature, contrasted with her own "butch" tendencies, foreshadows their later, complex mirroring of "inverted" gender expressions.

Opposite reflections. Alison describes herself as "Spartan to my father's Athenian. Modern to his Victorian. Butch to his Nelly. Utilitarian to his aesthete." This stark contrast highlights their inverse relationship: her father, a closeted gay man, adopted a hyper-masculine facade while indulging in feminine aesthetics, while Alison, a lesbian, embraced a more masculine presentation. Their "war of cross-purposes" was "doomed to perpetual escalation," as they both sought what the other embodied.

A demilitarized zone. Despite their inversions, a "slender demilitarized zone" existed between them: "our shared reverence for masculine beauty." However, even this shared appreciation diverged in its application. Alison desired "the muscles and tweed" for herself, while her father sought "the velvet and pearls" subjectively. This complex dynamic of attraction and repulsion, mirroring and opposition, defined their unique and often unspoken bond.

7. The Weight of Secrets: A Pervasive Family Atmosphere

HIS SHAME INHABITED OUR HOUSE AS PERVASIVELY AND INVISIBLY AS THE AROMATIC MUSK OF AGING MAHOGANY.

An invisible presence. The father's "fully developed self-loathing" and "shame" were not merely personal burdens but an invisible, pervasive force within the Bechdel household. Alison describes it as an "aromatic musk of aging mahogany," suggesting its deep-seated, almost structural presence. This unspoken shame dictated the family's emotional climate, making physical affection "a dicier venture" and criticism impossible.

The cost of concealment. The father's "skillful artifice" was primarily aimed at concealing his true identity, creating a "sham" family and a house that was a "simulacrum." This constant pretense led to a lack of "elasticity" and a pervasive tension. The family's emotional distance was so profound that Alison's parents seemed "almost embarrassed by the fact of their marriage," avoiding terms of endearment and even each other's given names.

A "mildly autistic colony." Alison reflects that if their home was an "artists' colony" where each was absorbed in "separate pursuits," it could "even more accurately be described as a mildly autistic colony." This metaphor captures the profound isolation and self-absorption that characterized their family life, where individual creative pursuits became a "compulsion" and a means of self-sustenance in the absence of genuine emotional connection.

8. Childhood Compulsions: A Response to Unspoken Tensions

MY ACTUAL OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER BEGAN WHEN X WAS TEN.

A need for control. Alison's obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) emerged at age ten, manifesting as a need to control her environment through counting, avoiding "odd numbers and multiples of thirteen," and meticulously arranging objects. This rigid adherence to ritual was a coping mechanism, a desperate attempt to impose order on a chaotic and emotionally volatile household filled with unspoken secrets and tensions.

Invisible threats. Her compulsions escalated to include an "invisible substance that hung in doorways" and between "all solid objects," which she constantly had to "gather and disperse." This "noxious substance" symbolized the pervasive, unseen anxieties and "dark fear of annihilation" that permeated her childhood, a direct reflection of the father's hidden life and the family's emotional repression.

A self-parenting child. Alison's engagement with Dr. Spock's book on child development, where she read about compulsions, was a "curious experience in which I was both subject and object, my own parent and my own child." This act of self-diagnosis and self-guidance highlights the emotional neglect within the family, where she had to "feed myself" and navigate her psychological struggles largely alone, using external frameworks to understand her internal world.

9. Historical Echoes: Personal Lives Amidst Societal Shifts

IT HAD ONLY BEEN A FEW WEEKS SINCE THE STONEWALL RIOTS, I REALIZE NOW.

A confluence of events. Alison's personal coming-of-age was intertwined with significant historical events. Her first period, her father's legal troubles for "furnishing a malt beverage to a minor" (a cover for his sexual encounters), and the Watergate scandal all converged during the summer she turned thirteen. This "heavy-handed plot device" of history mirrored the "chaos" and "poltergeists" of her hormonal fluctuations and family turmoil.

Queer history's backdrop. The narrative places the family's story against the backdrop of queer history. Alison's visit to New York City in 1976, at age fifteen, coincided with the Bicentennial and the "orgiastic" atmosphere that preceded the AIDS epidemic. She later realizes her visit to Christopher Street was just weeks after the Stonewall Riots, sensing a "lingering vibration, a quantum particle of rebellion" in the air, connecting her personal awakening to a larger movement.

The AIDS shadow. Alison contemplates her father's potential fate had he lived beyond 1980, imagining him lost to the "more painful, protracted fashion" of AIDS. This hypothetical scenario allows her to "displace my actual grief with this imaginary trauma," linking her "senseless personal loss" to a "more coherent narrative" of injustice and sexual shame. This connection, however, makes it "harder for me to blame him," complicating her feelings towards his life and death.

10. The Antihero's Journey: Reconciling Loss and Truth

DID BLOOM DISCOVER COMMON FACTORS OF SIMILARITY BETWEEN THEIR RESPECTIVE LIKE AND UNLIKE REACTIONS TO EXPERIENCE?

A vicarious journey. Alison's college English class on Ulysses, her father's favorite book, became her "Odyssey," a "gradual, episodic, and inevitable convergence with my abstracted father." This intellectual journey, initially "galling" due to her father's vicarious enthusiasm, ultimately brought them closer, as books continued to be the "currency" of their relationship, even as she navigated her own burgeoning queer identity.

The "Ithaca moment." The most profound connection occurred during a car ride to a movie, where her father, prompted by Alison's subtle inquiry about a Colette book, confessed his own homosexual experiences. This "sobbing, joyous reunion of Odysseus and Telemachus" was their "Ithaca moment," a brief, raw exchange of truth that transcended their usual emotional distance. It was a moment of shared vulnerability, where the roles of "father" and "child" blurred.

Reconciling the past. Despite this fleeting intimacy, the father's death left Alison with unresolved questions and a profound sense of loss. She grapples with his inability to "say yes to his own life" despite admiring Joyce's "lengthy, libidinal 'Yes'." Ultimately, Alison's "antihero's journey" is one of reconciling her father's complex legacy—his artifice, his secrets, his shame—with her own truth, finding her voice and narrative in the wake of his ambiguous end.

Last updated: