Key Takeaways

1. The World is Simple: Embrace Teleology, Deny Trauma

None of us live in an objective world, but instead in a subjective world that we ourselves have given meaning to.

Subjective reality. The world isn't inherently complicated; we make it so through our subjective interpretations. Our perception of reality is unique, like well water feeling cool in summer and warm in winter, despite its objective temperature. If we change our perspective, the world will appear simpler.

Teleology over etiology. Adlerian psychology rejects the Freudian notion of trauma and determinism, which posits that past causes dictate our present and future. Instead, it champions teleology, asserting that we are driven by present "goals." For example, a person's anxiety isn't caused by past trauma, but rather created as a means to achieve a present goal, such as avoiding social interaction.

Courage to change. We are not victims of our past or emotions. Anger, for instance, is not an uncontrollable impulse but a tool we fabricate to achieve a goal, like asserting dominance. People can change at any time, regardless of their environment, by choosing a new lifestyle. The only thing holding us back is a lack of courage to be happy.

2. All Problems Stem from Interpersonal Relationships

To get rid of one’s problems, all one can do is live in the universe all alone.

Interpersonal core. All human problems, even seemingly individual ones like self-dislike, are fundamentally interpersonal relationship problems. Loneliness, for example, requires the presence of others to be felt. If one were truly alone in the universe, the very concept of problems would cease to exist.

Self-dislike as a goal. Disliking oneself, focusing on shortcomings, and having low self-esteem can be a strategic goal. It serves as a defense mechanism to avoid the pain of being disliked or hurt in interpersonal relationships. By retreating into a shell of self-deprecation, one creates an excuse for not engaging with others, thereby protecting oneself from potential rejection.

Inevitable hurt. Engaging in interpersonal relationships inevitably involves some degree of hurt, both given and received. The desire to avoid this hurt entirely is unrealistic. Adler suggests that the only way to truly eliminate problems is to live in complete isolation, which is impossible for social beings.

3. Life is Not a Competition: Overcome Inferiority Complexes

A healthy feeling of inferiority is not something that comes from comparing oneself to others; it comes from one’s comparison with one’s ideal self.

Pursuit of superiority. Everyone possesses a "pursuit of superiority," a universal desire to improve and move towards an ideal state. This is a healthy drive for growth. Feelings of inferiority arise when we compare our current self to this ideal, acting as a stimulant for striving.

Inferiority vs. superiority complex.

- Feeling of inferiority: A normal, healthy awareness of one's current state compared to an ideal, motivating growth.

- Inferiority complex: Using feelings of inferiority as an excuse to avoid effort or responsibility (e.g., "I'm not educated, so I can't succeed"). This implies, "If only I weren't X, I could be Y."

- Superiority complex: A fabricated sense of superiority, often manifested through boasting or "giving authority" (e.g., name-dropping, flaunting wealth). This is a compensatory mechanism for deep-seated inferiority.

Comrades, not enemies. Viewing life as a competition, where there are winners and losers, inevitably leads to seeing others as enemies. This creates a constant state of anxiety and distrust, preventing genuine happiness. Instead, we should see others as comrades, celebrating their happiness and contributing to it, fostering a sense of safety and cooperation.

4. Achieve Freedom by Discarding Other People's Tasks

There is no need to be recognized by others. Actually, one must not seek recognition.

Deny desire for recognition. The universal desire for recognition, often stemming from reward-and-punishment education, is a trap. Living to satisfy others' expectations means living their lives, not your own. True freedom comes from not needing external validation.

Separation of tasks. Interpersonal problems arise from intruding on others' tasks or allowing others to intrude on yours. To achieve freedom, calmly delineate: "Whose task is this?" The person who ultimately receives the consequences of a choice owns the task. For example, a child's studying is their task; a parent's role is to offer support, not force.

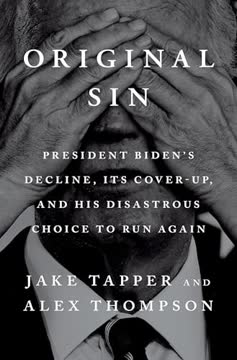

The courage to be disliked. The cost of freedom in interpersonal relationships is the possibility of being disliked. Not wanting to be disliked is a natural inclination, but constantly trying to please everyone leads to an unfree, inauthentic life. To live authentically and according to one's own principles, one must not be afraid of being disliked.

5. You Are Not the Center of the World: Cultivate Community Feeling

While the “I” is life’s protagonist, it is never more than a member of the community and a part of the whole.

Holistic individual. Adler's "individual psychology" emphasizes holism, viewing humans as indivisible wholes where mind and body, reason and emotion, are interconnected. We choose our actions as a unified self, rather than being controlled by separate emotions or unconscious drives.

Beyond self-centeredness. People obsessed with recognition are self-centered, constantly focused on how others perceive them. They act like "the world's protagonist," expecting others to serve their needs. This mindset inevitably leads to disillusionment and a loss of comrades.

Community feeling (social interest). The ultimate goal of interpersonal relationships is "community feeling," a sense of belonging and seeing others as comrades. This involves shifting from "attachment to self" to "concern for others," asking "What can I give to this person?" rather than "What will this person give me?" This sense of belonging is actively acquired through contribution, not passively received.

6. Build Horizontal Relationships: Encourage, Don't Praise or Rebuke

In Adlerian psychology, we take the stance that in child-rearing, and in all other forms of communication with other people, one must not praise.

Vertical vs. horizontal. Praise and rebuke both stem from vertical relationships, where one person judges another as superior or inferior. Praise, like rebuke, is a tool for manipulation, unconsciously creating a hierarchy. Adlerian psychology advocates for horizontal relationships, where all individuals are "equal but not the same."

The encouragement approach. Instead of praise or rebuke, foster "encouragement." This is assistance based on horizontal relationships, where one helps another gain the confidence to face their tasks independently. It's about conveying gratitude and respect, not judgment.

Feeling of worth. True self-worth comes from feeling "I am beneficial to the community," or "I am of use to someone." This feeling is not dependent on external praise but on one's subjective sense of contribution. Words like "Thank you" or "That was a big help" affirm one's usefulness without creating a hierarchical dynamic.

7. Embrace Self-Acceptance and Unconditional Confidence in Others

It is only when a person is able to feel that he has worth that he can possess courage.

Self-acceptance, not affirmation. Instead of self-affirmation (lying to oneself about capabilities), practice self-acceptance. This means acknowledging "one's incapable self" as is (e.g., a 60% score) and then focusing on what can be changed to improve. This "affirmative resignation" involves accepting what is irreplaceable and having the courage to change what is within one's power.

Confidence over trust. Interpersonal relationships should be built on "confidence," which is unconditional belief in others, even without objective grounds. "Trust," by contrast, is conditional (like bank credit). While unconditional confidence risks being taken advantage of, it's essential for building deep, meaningful relationships. Doubt, conversely, poisons relationships from the start.

Courage to believe. The courage to have unconditional confidence in others stems from self-acceptance. When one accepts oneself, the fear of being taken advantage of diminishes, as "taking advantage" becomes the other person's task. This allows for deeper connections and greater joy in life, even if it means experiencing occasional sadness.

8. Happiness is the Feeling of Contribution to Others

In a word, happiness is the feeling of contribution.

Contribution as self-worth. The only way to truly feel one's worth is through the feeling of "I am beneficial to the community" or "I am of use to someone." This "feeling of contribution" is the definition of happiness. It doesn't require visible contributions; a subjective sense of being useful is sufficient.

Work's true essence. Work, whether paid employment or household chores, is not merely a means to earn money. Its essence lies in making contributions to others and committing to one's community. Through work, one confirms their sense of belonging and existential worth. Even wealthy individuals engage in philanthropy to achieve this feeling.

Beyond hypocrisy. Contribution to others is not self-sacrifice or hypocrisy if it stems from seeing others as comrades. When family members are viewed as comrades, doing dishes or other chores becomes a natural act of contribution, fostering a positive atmosphere rather than resentment. This circular relationship between self-acceptance, confidence, and contribution forms community feeling.

9. Find Courage to Be Normal and Live Earnestly in the Here and Now

Why is it necessary to be special? Probably because one cannot accept one’s normal self.

The pursuit of easy superiority. Children (and adults) often seek to be "special beings" to gain attention. When being "especially good" fails, they may resort to being "especially bad" (problem behavior, delinquency) as an easier path to attention. This "pursuit of easy superiority" avoids healthy effort and seeks validation through negative means.

Courage to be normal. Rejecting normality often stems from equating it with incapability. However, being normal is not inferior; it is the default state for everyone. The "courage to be normal" means accepting oneself as ordinary, without needing to flaunt superiority or seek special attention. This acceptance is a vital first step towards a dramatic shift in one's worldview.

Life as a series of moments. Life is not a linear story with a predetermined destination (kinetic life) but a "series of moments" lived "here and now" (energeial life). Like dancing, the goal is the act itself, not an endpoint. Planning for a distant future or dwelling on the past postpones life. Living earnestly in each moment, without grand objectives, is itself a complete and fulfilling dance.

10. Assign Meaning to Life Through Contribution: If I Change, the World Changes

Whatever meaning life has must be assigned to it by the individual.

Life's inherent meaninglessness. Life in general has no inherent meaning. When confronted with tragedies, it's impossible to find universal meaning. However, this doesn't lead to nihilism. Instead, it empowers individuals to assign their own meaning to life.

The guiding star. When lost in the pursuit of freedom and happiness, Adlerian psychology offers a "guiding star": contribution to others. As long as one keeps this star in sight, one will not lose their way, regardless of external circumstances or whether others dislike them. This allows one to live freely and do whatever they like.

Personal power to change. The profound realization is that "my power is immeasurably great." If "I" change, the world will change. This means the world can only be changed by oneself. Just as putting on glasses clarifies a nearsighted world, embracing Adler's philosophy can transform one's perception, making life's outlines well-defined and colors more vivid.

Last updated:

Review Summary

The Courage to Be Disliked receives mostly positive reviews, with readers praising its introduction to Adlerian psychology and life-changing insights. Many find the book's message of self-acceptance and living in the present moment valuable. Some readers appreciate the conversational format, while others find it repetitive or difficult to follow. The book's simplicity and easy-to-understand language are highlighted as strengths. Critics note that the dialogue style can be tiresome, and some wish for more in-depth exploration of the concepts presented.

Similar Books