Key Takeaways

1. India's Unequal Prosperity: The "Beautiful Forevers" Divide

“Everything around us is roses,” Abdul’s younger brother, Mirchi, put it. “And we’re the shit in between.”

Stark contrast. Annawadi, a Mumbai slum, exists in the shadow of gleaming luxury hotels and a modern international airport, symbolizing India's rapid economic growth. This proximity highlights the extreme disparity between the "overcity" of wealth and the "undercity" of poverty, where residents literally live on land owned by the Airports Authority of India. The "Beautiful Forever" slogan on a wall separating the slum from the airport serves as a constant, ironic reminder of this divide.

Hidden costs. The prosperity of the overcity is often built upon the hidden labor and suffering of the undercity. Thousands of waste-pickers, like Abdul, scavenge the eight thousand tons of garbage Mumbai extrudes daily, turning discarded luxury into meager livelihoods. The construction of new terminals and infrastructure, while signifying progress, also threatens the very existence of the slums, as authorities seek to "cleanse" the city's image.

Globalized aspirations. The slum dwellers are not immune to the aspirations of the new India, fueled by television and glimpses of luxury. They dream of clean jobs, college degrees, and modern amenities, but these dreams are constantly juxtaposed with the harsh realities of their environment:

- Sewage lakes

- Rats and disease

- Lack of basic sanitation

- Provisional housing

2. Corruption: A Survival Mechanism, Not Just a Moral Failing

“Corruption, it’s all corruption,” Asha told her children, fluttering her hands like two birds taking flight.

Pervasive system. In Annawadi, corruption is not an anomaly but an integral part of daily life, a parallel economy that dictates access to resources and opportunities. From police demanding bribes for minor infractions to officials siphoning funds from anti-poverty schemes, the system is rigged, forcing residents to engage in it for survival. Asha, an aspiring slumlord, masterfully navigates this landscape, understanding that it's "one of the genuine opportunities that remained."

Transactional relationships. Every interaction, from securing a public water tap to avoiding false charges, often involves a transaction. Asha, for instance, leverages her connections with politicians and police to gain influence, offering services to her neighbors for a commission. This creates a complex web of dependencies where favors are rarely free, and even acts of kindness can have a hidden financial motive.

Exploiting vulnerability. The corrupt system preys on the most vulnerable, turning their desperation into profit. Government programs designed to help the poor, such as subsidized loans for entrepreneurs or education initiatives, are often co-opted by officials and their collaborators. Asha herself participates in a scheme to defraud a central government education program, rationalizing it as a necessary means to secure her family's future.

3. Dreams and Desperation: Ambition in the Undercity

Annawadians now spoke of better lives casually, as if fortune were a cousin arriving on Sunday, as if the future would look nothing like the past.

Unwavering hope. Despite living in extreme poverty, Annawadi residents harbor ambitious dreams, fueled by India's economic boom and the tantalizing proximity of wealth. They envision futures vastly different from their present, believing in "New Indian miracles" that can lift them from their circumstances. These aspirations range from personal betterment to family advancement:

- Mirchi dreams of a clean job in a luxury hotel.

- Manju aims to be Annawadi's first female college graduate.

- Sunil, a young scavenger, wants to eat enough to grow taller.

- Asha seeks to become a powerful slumlord and politician.

Clash with reality. These dreams often collide with the harsh realities of the slum, where opportunities are scarce and systemic barriers are formidable. Mirchi's hotel job is temporary and exploitative, Manju's education is undermined by her mother's schemes, and Sunil's growth is stunted by hunger. The pursuit of these dreams can lead to profound disappointment and even tragedy.

Incremental gains. For many, progress is not a sudden leap but a series of small, hard-won battles. Abdul, through diligent garbage sorting, slowly improves his family's living conditions, replacing a sheet divider with a brick wall. Asha's rise to slumlord is a gradual accumulation of influence, built on solving neighbors' problems and navigating political machinations. These incremental gains, however, are always precarious and subject to reversal.

4. The Fragile Thread of Life and Arbitrary Justice

To be poor in Annawadi, or in any Mumbai slum, was to be guilty of one thing or another.

Precarious existence. Life in Annawadi is constantly threatened by illness, accidents, and violence. Danush, a baby, is severely burned by his father, and children are routinely hit by cars on chaotic roads. The public hospitals, meant to serve the poor, are often understocked and neglectful, turning minor ailments into fatal conditions. The Mithi River, once a source of fish, becomes a dumping ground with a "body count."

Justice for sale. The Indian criminal justice system, rather than protecting the innocent, operates as a "market" where innocence and guilt can be bought and sold. Abdul and his father, falsely accused of inciting Fatima's suicide, face beatings and prolonged detention unless they pay bribes. The police prioritize profit over truth, often fabricating evidence or coercing witnesses.

The cost of truth. Speaking the truth can be dangerous and costly. Witnesses in the Husain trial, like Dinesh, risk losing a day's wages to correct false police statements. Fatima's husband, initially truthful, eventually fabricates testimony to secure a conviction against the Husains, driven by grief and a desire for vengeance. The system incentivizes dishonesty, making it nearly impossible for genuine justice to prevail.

5. Identity's Weight: Caste, Religion, and Gender in the Slum

“In your mind, you’ve already moved to Vasai,” she told her husband, ladling out the stew and handing it over with the economy of motion people develop when living in small, overpopulated huts. “Maybe you should pack up and go. And then go to Saudi—oh, there you can really relax! But this house is where your wife and children live. Look at it. You also felt ashamed when that imam came over.”

Enduring divisions. Despite Mumbai's cosmopolitan image, traditional caste and religious prejudices profoundly shape opportunities and social interactions. Shiv Sena, a dominant political party, actively campaigns against migrants and Muslims, making Abdul's family "twice suspect." Dalits, historically "untouchables," occupy the lowest rung of the social hierarchy, facing systemic discrimination.

Gendered struggles. Women in Annawadi face unique challenges, often navigating patriarchal expectations alongside poverty. Manju, despite her college education, is expected to fulfill traditional household duties and fears an arranged marriage that would confine her to village life. Asha, in her pursuit of power, must contend with men who initially dismiss her and later exploit her. The "One Leg," Fatima, is marginalized due to her disability and her perceived sexual promiscuity.

Internalized prejudice. The characters often internalize these societal biases, influencing their self-perception and interactions. Abdul's father dreams of moving to Vasai, a Muslim-majority community, partly to escape the religious insults his family faces. Asha, despite her own humble origins, judges other women based on their perceived "low-class" behavior, reflecting a desire to distance herself from her past.

6. Internal Strife: When the Powerless Turn on Each Other

Poor people didn’t unite; they competed ferociously amongst themselves for gains as slender as they were provisional.

Envy and resentment. In a zero-sum environment where resources are scarce, Annawadians often turn their frustrations and envy against each other rather than uniting against systemic injustice. The Husains' modest success in the garbage business sparks resentment from neighbors like Cynthia and Fatima, leading to destructive conflicts. Fatima's self-immolation, while a desperate act, is also a weaponized accusation against the Husains.

Destructive cycles. The cycle of blame and retaliation perpetuates suffering within the community. Fatima's death, initially a personal tragedy, becomes a catalyst for further strife, with rumors of curses and accusations flying. The police exploit these internal divisions, using them to extract bribes and maintain control, rather than fostering peace.

Lack of collective action. Despite shared grievances like water shortages, voter disenfranchisement, and exploitative labor practices, the slum dwellers rarely unite for collective action. Their hopes and angers are "privatized," making them easier to control and exploit. The animal rights activists, in contrast, successfully mobilize public outrage over Robert's horses, highlighting the stark difference in how different forms of suffering are perceived and addressed.

7. The Scavenger's Resilience: Finding Value in Discarded Lives

Every morning, thousands of waste-pickers fanned out across the airport area in search of vendible excess—a few pounds of the eight thousand tons of garbage that Mumbai was extruding daily.

Resourceful survival. The waste-pickers of Annawadi, despite their stigmatized profession, demonstrate remarkable ingenuity and resilience. They meticulously sort through society's discards, transforming "worthless" trash into valuable commodities. Abdul, with his keen sorting skills, elevates his family above subsistence, while Sunil discovers hidden niches like the "ledge" above the Mithi River to maximize his earnings.

Harsh realities. This work, however, comes at a severe cost. Scavengers face constant dangers:

- Infections from dumpster diving

- Maggots and lice

- Gangrene and lung diseases

- Violence from competitors and police

- Stunted growth due to malnutrition

Unseen labor. The scavengers' labor, though essential to the city's waste management, remains largely invisible and unappreciated by the overcity. They are often called "garbage" themselves, reflecting the dehumanizing nature of their work. Yet, their ability to extract value from refuse is a testament to their adaptability and determination to survive against overwhelming odds.

8. The Illusion of Meritocracy: Effort vs. Exploitation

“The big people think that because we are poor we don’t understand much,” she said to her children. Asha understood plenty.

Effort unrewarded. The book consistently challenges the notion that hard work and virtue are reliably rewarded. Abdul, who works tirelessly and strives for honor, finds his business undermined by police corruption and his family entangled in a false murder charge. Mr. Kamble, a hardworking toilet cleaner, dies for want of a heart valve despite his efforts to secure a loan.

Exploitation as a path. Conversely, those who master the art of exploitation and manipulation often find greater success. Asha, through her cunning and willingness to engage in corrupt schemes, rises to become the most influential woman in Annawadi. She leverages her political connections and even defrauds government programs, demonstrating that in this "rigged market," ethical boundaries are often fluid.

The "big people's" game. The "big people" – politicians, officials, and wealthy developers – operate by a different set of rules, where power and connections trump merit. They divert public funds, engage in land speculation, and manipulate the justice system for personal gain. Asha, observing this, concludes that "becoming a success in the great, rigged market of the overcity required less effort and intelligence than getting by, day to day, in the slums."

9. Narrative as Power: Shaping Truth in a Flawed System

Innocence and guilt could be bought and sold like a kilo of polyurethane bags.

Controlling the story. In a system where truth is malleable, the ability to control the narrative becomes a powerful tool. Fatima, after her self-immolation, is coached by a "special executive officer" to craft a revised statement that falsely implicates the Husains, making her accusation more "plausible" for a criminal case. This demonstrates how official narratives can be manufactured to serve specific interests.

Selective reporting. The media and authorities often present a distorted reality, particularly concerning the poor. Kalu and Sanjay's deaths, likely murders or suicides driven by police brutality, are officially recorded as "tuberculosis" or "heroin overdose" to maintain a facade of public safety and avoid inconvenient investigations. The focus shifts to "solvable" cases, like the cruelty to Robert's horses, which generate public outrage and positive headlines.

The power of perception. Public perception, often influenced by rumors and stereotypes, can be more impactful than factual evidence. Fatima's act is reinterpreted by Annawadi women as a "flamboyant protest" against various injustices, rather than a desperate act fueled by envy and a crumbling wall. This re-framing highlights how collective narratives can shape memory and meaning, even in the face of contradictory evidence.

10. The Quest for Dignity: Becoming "Ice" in Dirty Water

“For some time I tried to keep the ice inside me from melting,” was how he put it. “But now I’m just becoming dirty water, like everyone else. I tell Allah I love Him immensely, immensely. But I tell Him I cannot be better, because of how the world is.”

Maintaining integrity. Amidst the pervasive corruption and moral compromises, characters like Abdul strive to maintain their dignity and a sense of honor. Abdul, inspired by his teacher at Dongri, attempts to live a "virtuous path," refusing to buy stolen goods and seeking justice through the legal system, even when it means personal sacrifice. He yearns to be "ice" in Mumbai's "dirty water," distinct and pure.

The toll of the system. However, the relentless pressure of the corrupt system gradually erodes this idealism. Abdul's efforts to be honorable lead to financial hardship for his family and prolonged legal limbo. He eventually questions his ability to maintain his ideals, feeling himself "just becoming dirty water, like everyone else," acknowledging the immense difficulty of resisting systemic forces.

Small acts of defiance. Despite the overwhelming odds, small acts of dignity and compassion persist. Manju, in her hut school, dedicates herself to educating children, offering them a glimpse of a better future. Sunil, despite his harsh life, finds solace in protecting the parrots and forming a genuine friendship with Sonu. These moments, though fleeting, represent a quiet resistance against the dehumanizing forces of the slum, a testament to the enduring human spirit.

Last updated:

Review Summary

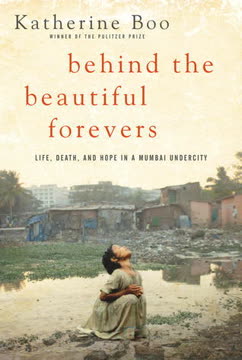

Behind the Beautiful Forevers examines life in Annawadi, a Mumbai slum near luxury hotels and the international airport. Reviewers praise Katherine Boo's meticulous four-year immersive research and compelling narrative style that reads like fiction while documenting real people's struggles. Most found it eye-opening and disturbing, highlighting pervasive corruption across all levels of Indian society—police, hospitals, schools, and charities. The book depicts extreme poverty, hopelessness, and how residents compete rather than unite. While some criticized the narrative approach or found it emotionally distant, many called it powerful, unforgettable, and essential reading about global inequality and resilience amid impossible circumstances.

Similar Books